Guest post by Jo Ann Schneider:

If popular opinion is to be believed, then characters are the reason people love stories. I know readers who will, if they do not find a character that they like in the first twenty pages of a book, toss the volume aside and send a prayer of thanks to whatever deity they worship that they got the book from the library. Or watched the show on Netflix.

Why jump in and make the commitment to a story if you’re not sure you care about what happens? We’re all busy, right? I, personally, have better things to do with my emotions.

However, just as soon as the victim, er, reader, gets caught up in some aspect of the characters, they’re hooked. They’re in. They’ll dredge through bad dialogue, horrible action scenes or a love interest that doesn’t deserve the character to get to the end. To see what happens. Does the hero overcome the bad guys? More importantly, does he figure out that he needs his friends to get through this mess, because he can’t do it alone?

I once heard an analogy that went something like this:

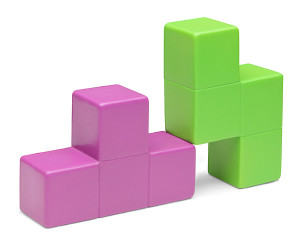

There are two kinds of obstacles in life, the boxes and the holes.

Boxes are those unexpected curve balls that life throws at us. Things like a break up, the death of a

loved one, the loss of a job, finding out your best friend is sleeping with your boyfriend, the furnace dying or your car catching fire on the freeway.

We’re in a crazed version of Tetris where the sole purpose of the game is for our author to surround us with more boxes than we can deal with. They get dropped in front of us, behind us, to the sides. Sometimes you have to dodge them as they come down. And there’s nothing we can do about it.

Go ahead, shake your fist, it won’t help, but it might make you feel better.

Holes are an entirely different matter. Holes are our own issues. Those problems that we have a hard time seeing in ourselves, and if we happen to catch a glimpse, we look away and pretend it was the dog or perhaps the wind.

Kind of like cookies.

I love cookies. I can, sometimes, consider them boxes. This especially works when they appear at home or at the office. I have to do something about them, right? Can’t just leave them sitting around.

But then there are the times that I walk through the bakery at the store. Or past the gigantic display of Oreos (seriously, those things are out of control). I know that if I see a cookie I will more than likely buy and then eat a cookie. Avoidance is the key here.

But I kind of love cookies.

At some point in my life I noticed this problem. Probably when I looked down and found an entire row of Oreos had disappeared, and I was home alone. Oops. My bad. Maybe I have a problem. Or I just had a bad day. That’s it, a bad day. There’s nothing wrong with cookies, right?

No, cookies are fine, for other people. For me they are a huge hole that I try to ignore but often fall into. More often then I want to admit

A character in a story needs holes in their life. A flaw that is somewhat obvious to the audience, but not so much to the character. Or if the character knows it is a problem, they’ve “got it under control.” The character needs to fall into the hole a few times. If they don’t then they’ll never change. A good story should be the account of the character finding the hole and figuring out how to plug it up so it won’t be a problem anymore.

Have you ever had to do something you really didn’t want to? Say shovel the walks? How many times can you talk yourself out of it? How may excuses can you come up with to delay in the hopes that someone else will do it? And how do you feel when you finally have to bite the bullet? There might be some grumbling. Crying. Tossing offending gloves around in the closet before you find yours. There will probably be stomping as you take the longest route to the garage—past as many people as possible—punctuated by a nice, solid, door slam as you finally go out to face the snow.

Characters go through this too. They need to see the hole, acknowledge the hole, stare it down—they

don’t have to be happy about it—before they finally pull the plug out of their, uh, you know, and shove it in place so they won’t fall in again. Ever.

This moment is why the reader didn’t put the book down after twenty pages. This is when the character pulls his head out and gets smart.

Bad things have happened, the character has reached the finale of the tale, his posse is close, the bad guys have pulled out all of their stops, which have in fact stopped the character in his or her tracks. The bad guy chuckles. The posse holds their collective breath and turn their eyes to the hero.

Will he be able to do it?

If every scene before this hasn’t led the audience to the conflict, then the story is missing something. If the author only gives the character a 2 x 4 to dance across the hole on like a wobbling balance beam instead a a nice, fat, plug, then the story is missing something. If the audience doesn’t both cringe and cheer the moment the hero hammers that plug in place, then the story is missing something.

Characters must have problems. What do they want? To save the world. What do they need? Well, now that’s the important bit.

Thanks for the laugh. And the help. This inspired me to try writing again. Someday I’ll have a story done from start to finish instead of a jumbled up mess of ideas.