A guest post by Karen Traviss.

Nobody wants to be the guy who said Krakatoa was east of Java. As storytellers, we know we need to get detail right if we tether our stories to the real world.

Nobody wants to be the guy who said Krakatoa was east of Java. As storytellers, we know we need to get detail right if we tether our stories to the real world.

I had a colleague in my TV days whose early novels, written in time snatched between shoots, involved a trip to a certain building in Europe to settle an argument with his editor about how many steps there were in front of its main doors. It mattered to him; I understand that compulsion. I’ll spend an entire day doing research that ends up as one line in a novel. And even if you set your story on an alien world or in a fantasy universe, there are hard facts – human behaviour, physics, or just a consistent world – that mean you have to do at least a minimal amount of research. It might not involve doing obsessive surveys of public buildings, but it has to be done. Mistakes aren’t just embarrassing; they can also derail your story if a key plot point you’ve relied on turns out to be impossible.

In our quest for technical accuracy, though, we can overlook more fundamental authenticity, the stuff that can shape and distort opinion in the real world. While misplacing Krakatoa is annoying, it isn’t going to influence what the audience feels about serious issues. But feeding people a steady diet of stereotypes and errors about a topic can embed an attitude that people carry with them into their real world opinions. That affects a lot of different groups, but it’s especially true of public perception of the armed forces.

Like it or not, fiction does seep into the public consciousness through constant exposure, and once it’s there, it’s hard to filter it from reality. It takes root where people have no personal experience of a topic to tell them that the fiction they’re absorbing is factually wrong, and it creeps up on even the smartest people. I’m not talking about using daft phrases like “Over and out” (which is meaningless, as “over” is the opposite of “out” in radio procedure) or having characters call sergeants “Sir.” I mean the fabric of what it means to serve and to fight – the attitudes and experiences of the soldier.

Should that seepage worry us as writers? I’d say it ought to. If people are forming opinions on defence and foreign policy based on fiction, we should attempt to do no harm, and doing no harm requires some work on our part. The armed forces aren’t the only sector of society that can fall victim to “false memory” opinions, but servicemen and women are unique in that we expect them to be willing to die for us as a fundamental condition of their job. No other workers, not even police or firefighters, have to accept death as a definite possibility in the same way. So we owe those who serve a duty of truth.

A few months ago, I watched a TV discussion that was a perfect example of fiction shaping someone’s perception of what our armed forces should do in the real world. It was a round-up of the day’s news stories, with celebs and other non-experts passing comment. One studio guest was furious that nobody had deployed helicopters to rescue refugees in a war zone. She seemed unaware that in this particular case, the distances and conditions meant it wasn’t physically possible. She thought she knew what helicopters could do, and was no doubt sincere in her outrage, but nevertheless she was utterly wrong. The studio anchor was equally ignorant and the debate continued without any input from someone who could say, “Actually, there’s no way we can do that, because… “

So why did they think they knew the facts? Where did they get their unrealistic ideas on helicopters and logistics of evacuations? I’d bet my pension fund that they’d absorbed some kind of pseudo-reality from TV and movies without even realising it. It wasn’t because they were stupid. It was because they were human and the gap in their knowledge had been filled by the nearest available data, provided by years of watching impossible feats performed in movies.

Few civilians in the UK or North America these days have any direct contact with service personnel, however supportive we think we are of our troops. Our forces have shrunk over the years, and there’s no conscription. Soldiering has become the career of a relatively small number of volunteers. But a couple of generations earlier, things were very different. In World War II, every British family had a direct link with combat and its consequences. Either someone in your family was serving, or your friends and neighbours were, and as a civilian you were subjected to multiple air raids and years of strict rationing. If you compare British war movies from the late 1940s and early 1950s to modern ones, they’re much more technical; producers couldn’t get away with mistakes because their audience knew the subject. They’d served or they knew someone who had.

There’s now a growing disconnection between the military and civilian worlds, and it’s not been entirely discouraged by governments trying to head off objections to foreign wars. These days, with our omniscient Hollywood perspective, we think a soldier has the same perfect awareness of a situation as the camera, and so we think we know that they ought to have done. Civilians make judgements, moral and tactical, without any real awareness of what it’s like to serve, let alone fight, unless they’re prepared to put in time watching documentaries. But even then factual programming can be variable in accuracy. I’ve seen historians locked in bitter arguments over events that were taught to me as established fact. If we can’t even rely on history, then finding a gold standard for military authenticity isn’t easy.

The best we can do as writers is the same as the best I could do as a journalist; we can talk to the primary sources, the men and women who’ve lived through it. Even if they don’t agree on everything – and there’s no such thing as a definitive view of a battle – they’re the nearest to the truth we’re ever likely to find in this world. The detail will vary from country to country and between branches of the services, but there are some things that are common to everyone who’s served. Those are the truths we need to seek and portray.

I was a news journalist for 20 years and spent ten years in PR for government organisations, so I formed a detailed picture of where people got their information and what influenced their thinking. Now that I write fiction instead, I treat it like a hazardous material because I know it has real consequences. It’s sobering to think that I might have imparted more understanding of military life to my civilian readership as a novelist than I ever achieved in my time as a defence correspondent. It’s even more sobering to think that understanding has been based mostly on SF, where the technical detail can as unreal as you want to it to be. The reality lies in honest depiction of the mind-set, sense of comradeship, and basic soldiering skills that would be as familiar to a Roman legionary as they would to a space marine with a laser weapon.

###

Visit the Fictorians tomorrow for Part Two.

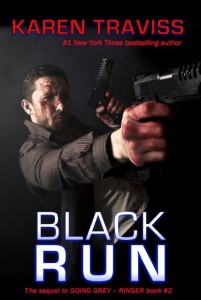

New York Times best-selling author Karen Traviss is a former defence correspondent and has also spent way too much of her life around politicians and police. Going Grey, the first in her new techno-thriller series, is out now and the sequel, Black Run, will be published this summer. Website and newsletter sign-up: www.karentraviss.com Twitter: @karentraviss

Excellent post, Karen. You’re absolutely right. It always confuses me why people turn to celebrities for advice on military, police, and complex political issues when they have no expertise in those areas more than perhaps pretending to be someone who knows in a TV show or movie.

I’ve been thinking of calling an acquaintance to ask about military tactics on a novel I’m working on. Now I’m definitely giving them a call. Thanks.

Pingback: Why We Need to Write the Military Right: Part Two - The Fictorians