A Guest Post by Abby Goldsmith

When Nathan Barra asked me to write a guest post about why I write fiction, I hesitated. It’s a good question, and one that I haven’t pondered in years. I’ve been stuck in a rut. Not writer’s block, but paralytic self-doubt, questioning everything about why I chose to pour so much of my life into a career as a novelist. I’ve watched others rise from amateur to best-seller within less than half the time I’ve been struggling to get my novel series published. I lag behind most of my peers, editing and rewriting and editing and rewriting. I’m in danger of becoming a bitter, grizzled veteran.

Self-doubt is a cornerstone of every novelist’s life, I think. When I talk to other aspiring novelists, I hear commonalities in our journey. Most of us grew up with a love of reading. Most of us received praise from readers who adored our stories. Most of us bashed our heads against the harsh realities of the publishing industry, which seems to be shrinking from corporate mergers. From there, our paths diverge in two directions. Either we give up and quit writing novels, or we get published and continue onwards.

My path feels like the most extreme version of that. Rather than hiking a trail towards success, I’m navigating a storm-tossed sea, hurled about by towering tidal waves. The praise I receive is enough for a lifetime. My failures are EPIC. As for the part where I either get published or quit . . . I’m sailing between those routes, unable to get my novels traditionally published, unable to give up and quit. I’m preparing to self-publish a completed six-book-series, and I’m nearly paralyzed with the fear that it will all go wrong.

Most people, even committed writers, don’t base every major decision of their life around the dream of becoming a bestselling author. I suspect that most of my peers would have quit after more than decade of setbacks. Why am I so driven?

Childhood. That’s surely where most addictions and personality disorders form, and I suspect it correlates with dysfunctional families. I won’t detail how troubled my childhood was. Suffice it to say, I needed an escape. So I walked for hours, listening to music, inwardly cheering as my characters delivered justice to their enemies, or proved their worth to those who doubted them. Stories were my only way to feel powerful and in control. That feeling was better than anything I could get elsewhere. I was addicted.

By the age of twelve, I’d completed two novels, a series of short stories, and a trilogy of comic books. A literary agent working with Random House, unaware that I was a child, read my first manuscript and sent a scathing rejection letter, including the phrase, “It sounds like a mentally challenged person wrote this.” Upon learning my age, she offered to edit my manuscript and promote me as a child author, but I’d already taken her first letter to heart. I decided that my stories were unfit to be shared with anyone. They collected dust in shoeboxes.

In college, two of my student films were selected out of hundreds for special recognition, and received high praise in international film festivals. I began a promising career as an animator. With my confidence boosted, I dared to share chapters of a potential novel with an online critique group. Their reactions astounded me. Everyone in the group wanted to read more. They tore each other’s work to shreds, and rightfully so, but my work was exceptional.

After years of being ashamed of my writing skill, I reversed direction all at once. A dam burst. Within the space of one year, I completed a 520,000 word manuscript, a 59,000 word manuscript between drafts of the big one, and an unfinished 70,000 word novel. My boyfriend thought they were amazing.

Still worried that my skill was amateur, I asked for readers with trepidation. Part of me expected scathing rejections. Instead, I received a flood of support and praise that changed my life, and affects me to this day.

A programmer in New Zealand read all my manuscripts, and said, “SEND MORE!” A teenager in Norway did the same, telling me that he’d missed classes to read them under his desk at school. A woman I never met emailed me to say, “Whatever gift for storytelling exists, you have it.” The artist of my favorite web comic offered to endorse my novels, after reading. A coworker at my office tentatively agreed to try the big one. He began reading it in his cubicle. The next day at work, he said, “I got no sleep. I stayed up all night turning pages! You’ll have no trouble getting published, so stop worrying.”

And I did. From that point forth, I’ve considered myself a talented storyteller, although my prose and craft needed seasoning, and there are always aspects where I can improve. Literary agencies and publishers rejected those early manuscripts due to the usual bouquet of amateur issues: Point of view head hopping, passive voice overused, weak verbiage, and other problems that are familiar to career-minded writers.

To improve my craft, I went to the Odyssey Writing Workshop. George R.R. Martin liked the first chapter of my big novel, Catherine Asaro privately praised my short story, and I felt as if my skill would leap ahead light years after all I learned from editor Jeanne Cavelos. Encouraged, I scrapped the 520,000 manuscript and rewrote it from scratch, as two separate novels. They’ve each been whittled down to the 90,000 to 105,000 word range.

I wish I could say that all that effort led to success. It hasn’t. At least, not yet. The massive rewrite deadened the beginning, and I’ve had a hellish time trying to get it to appeal to the traditional publishing industry. On top of that, I’m no longer the same person who wrote the original rough draft. Fifteen years have passed. I believe I understand why epic saga authors, such as Patrick Rothfuss, struggle to finish. When a story has the weight of a magnum opus … when it feels too massive to do it justice … when the task requires decades of your personal life … well, I can only speak for myself, but there’s a damned lot of pressure to get it right. A project that huge only happens once. Humans don’t live long enough, or have enough energy, to do it twice.

I will write other novels. I have other big stories to tell, after I publish this series (the first two books are the rewritten rough draft from fifteen years ago). But this epic will always be more special to me than any others. It’s the story that began in my teens, and spanned my twenties and thirties. It’s the one that shaped the course of my life.

I write because I believe in my power to tell stories that amaze people, and leave them to reevaluate their world-views.

About the Author:

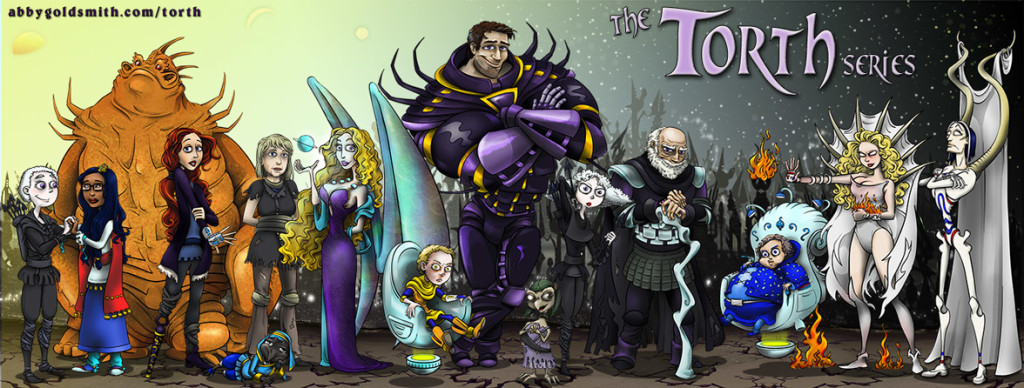

Stories and articles by Abby Goldsmith are published in Escape Pod, Fantasy Magazine, Suddenly Lost in Words, and several anthologies. She’s sitting on six unpublished novels, preparing for an epic debut. http://abbygoldsmith.com

Honored to occasionally sit at a table with you and write!