A scene is a unit of writing which moves the story forward. There are two types of scenes: action and reaction scenes. Action scenes have an objective, an obstacle and an outcome. Reaction scenes have emotion, analysis and decision. If you need more information on scenes and scene structure, I recommend James Scott Bell’s book Revision and Self-Editing for Publication.

THE STEPS

A) THE SET UP

This section is a lot of work, but the benefits are worth it. Chances are, if you have an agent or an editor (publishing house or otherwise) you’ll be asked to submit a scene outline.

1) Identify and number the scenes. If I am writing in chapters, I‘ll number the scenes for Chapter 1 as 1a, 1b, 1c. If I’m not writing chapters but scenes, I number them as I go along.

2) On a spread sheet, write a one sentence (or two at most) descriptor about each scene.

3) Identify whether a scene focuses on the main plot (M) or subplot (S). This will help you see what kind of balance or structure your plot has.

4) Write an About statement which explains your story. It should be only one sentence long. For example: This story is about a boy who must understand forgiveness to defeat an evil wizard to save his school. Put this line at the top of your chart for easy reference. Sometimes this is called theme.

5) Turn the About statement into a question. This is the story question and it is what the climax must answer. For example: To save his school, can the boy learn to understand forgiveness in time to defeat the evil wizard?

6) Note if scenes are Action, Dialogue, Exposition, or Reflection/Reaction. There are many more types of scenes, but I like to keep it fairly simple and use only four. This will reveal how the story is balanced. For example, are action scenes followed by reflection/reaction scenes? Are there too many exposition scenes? Too much exposition scenes may mean that there is too much telling and not enough showing or clumped together, they may halt the pace.

7) Create columns for General Notes, Character Appearances, POV, Time of Day/Location or other things important to your story. Then look for balance and continuity and logic problems. For example, if you have one main POV character, but interject with a secondary character, it wouldn’t make sense to have the bulk of middle chapters form the secondary character’s POV. If you do, then you have to decide whose story this is and find the appropriate story telling balance.

B) DECIDE IF SCENES ARE NECESSARY BEFORE YOU REVISE

Neglecting this step and revising before you understand the problems in each scene can be a waste of time. Why put the effort into revising only to discover it should be deleted or that it needs to be rewritten because it’s not doing an adequate job of moving the story forward. Or that a bridge scene needs ot be written for effective transition which means that the scenes before and after need to be changed.

1) Determine if each scene reflects or addresses what the story is about (step 4). Each scene must also work toward answering the story question (step 5), or in other words, each scene must work toward the climax.

2) At this point in the process, I look to apply the rule of three, where things should happen or appear at least three times. If they don’t either they’re not needed and should be eliminated or must be added. For example, I have one scene with a secondary character who has a small but important contribution to a murder investigation. I am thinking that I’d like her to appear in other books in the series. To make her contribution and her character more memorable, I need to include her at least two more times in the novel. This might be done by adding her into existing scenes or writing new scenes.

3) Ask if the scenes are hitting all the beats, all the points of good story telling structure. This may entail looking at your story from the Three Act Structure or the Hero’s Journey, for example. If you are missing the Crossing the Threshold Scene, write it now.

C) REVISE THE SCENES

Your story structure is fairly sound now because you’ve got the list, you know what type of scenes you have and if they’re hitting story telling beats. Now, you need to make each scene as strong as possible.

Every bit of dialogue, exposition, action and reflection must move the story forward. If it doesn’t, that scene isn’t doing its job and it’s muddying your story.

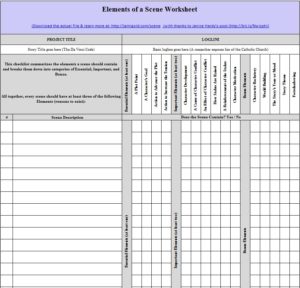

To help me analyse the power of my scenes and exactly what they’re contributing, I use Jami Gold’s Scene Checklist and note what is working for each scene. Jami’s checklist is very comprehensive and I think it’s a good starting point but you still must address each point critically.

When using Jami’s system, I discovered that I had too many scenes in a row which did not increase the stakes. Sure, there was tension in those scenes, but in terms of the story goal, the stakes weren’t being addressed.

When using Jami’s system, I discovered that I had too many scenes in a row which did not increase the stakes. Sure, there was tension in those scenes, but in terms of the story goal, the stakes weren’t being addressed.

So the Scene Checklist helped identify problems, but how do you address them?

For every scene, ask:

1) Does it advance the plot?

2) Does it reveal character?

3) Has something changed for the character?

4) If it is an action scene, does it have a clear objective, obstacle and outcome?

5) If it is a reflection/reaction scene, does it have clear emotion, analysis and description?

6) Is the dialogue succinct and does it move the story/plot forward?

7) Is the exposition clear and succinct, create tension, and move the story/plot forward?

8) How can I address the problem identified in the check list?

Subplot scenes must, in one way or another, affect or contribute to the plot by complicating the protagonist’s goals. This could be by producing emotional or physical obstacles. Subplots are great for revealing character and increasing personal stakes. Do your subplot scenes contribute to story in these ways?

Using these questions as a guide, look for ways to strengthen each scene so that it is doing it’s job and has maximum impact.

When you’re happy that the scene is doing the work that you need it to, then it’s time to polish and make sure that every line and every word is doing it’s job, that voice is active not passive, that those pesky -ly words are minimized and you are showing and not telling, and dialogue is crisp and clean.

Revising scenes is a long hard process, there’s no doubt about that but the rewards of producing units of writing with maximum impact are certainly worth it for you and your readers!