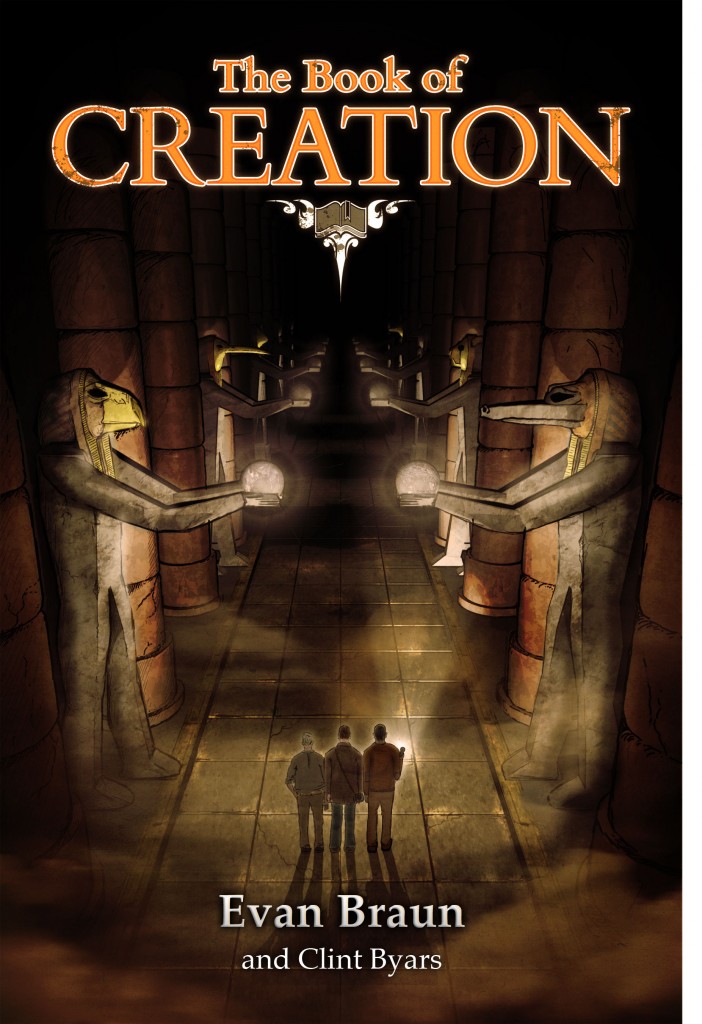

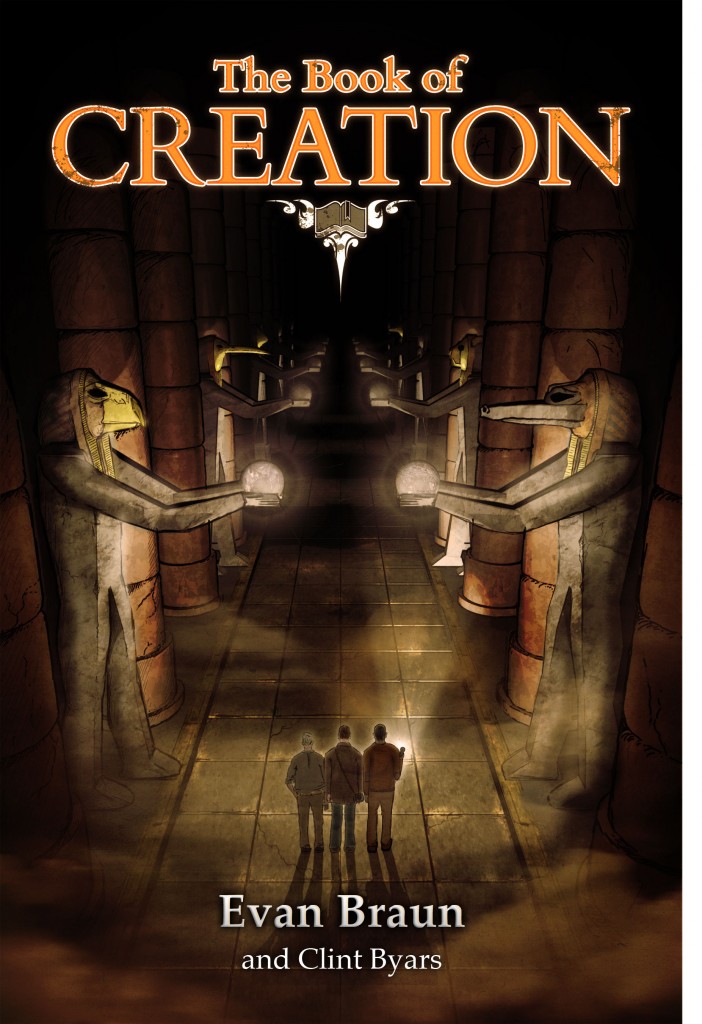

In the wake of a discovery that rocks the archaeological world, three strangers meet for the first time in the mountains of central Switzerland. Under a cloak of secrecy, they’ve been gathered together by a ruthless billionaire whose goal is to harness unspeakable power by unearthing an artifact more ancient than civilization itself.

Their mission soon finds them on the chase of a lifetime. From the Great Pyramids of Egypt through the wilds of Antarctica, they circle the globe on the heels of a mystery thousands of years in the making, pursued by forces intent on their destruction, proving once and for all that there are some mysteries in this world too dangerous to be solved…

For in the dark waits a terrifying menace.

* * *

As a regular contributor to The Fictorian Era, over the last year I have shared with you my views on writing, publishing, and my general sanity. Well, obviously the goal of all that blood and sweat is to achieve the dream of being a published author. Slowly but surely, a lot of us Fictorians are starting to see the fruits of our labor pay off. As each of us comes out with a new book, we’re excited to share the news with you, our readers. Today, I have just such a piece of good news!

Authors can often trace their labors of love back through the years. Well, this week, after more than five years of hard work and tireless research, I am pleased to announce the release of the writing project I am most proud of.

The Book of Creation, a novel written by myself and Clint Byars, will be published in print this upcoming March from Word Alive Press. However, for those of you who own Kindles and other ebook reading devices, the book is being made available early. It is now available for purchase from the Kindle Store, and in the coming weeks it will pop up in all the major ebook venues. It’s priced at just $2.99. Even if you’re not a Kindle owner, there’s an option to purchase the book as a gift for friends and family who are Kindle owners. The book would make a great, inexpensive Christmas gift. Think of it as a digital stocking stuffer!

The novel is an exploration of the premise that our ancient history is fundamentally different from the prevailing historical views of our times. Similar in vein and style to Indiana Jones and The DaVinci Code, this novel presupposes that elements of the world’s greatest mythologies have a kernel (perhaps a large kernel) of truth… a truth which is finally coming to light after thousands of years hidden in the dark.

And now, without further ado, here is an exclusive preview of The Book of Creation:

* * *

Emery Wörtlich was disappointed. At this point in his career, he would have expected more than a half-empty lecture hall. And if this class went anything like the ones preceding it, the numbers would dwindle to a mere handful by the time he presented his more controversial theories. If he had learned anything as a professor, it was that students couldn’t be bothered to think for themselves anymore.

If I change even one mind, it will be worth it. Of course, he would have preferred to change several hundred at a time.

“Good evening,” Wörtlich said, a slight German accent clipping the edges of his words. He unzipped his bag and pulled out a laptop, placing it softly on the lectern. He double-clicked on his presentation file and turned back to the class as the screen lit up.

Sadness once again took hold as he counted the number of empty seats between filled ones.

“Today we look at the Giza pyramids,” he said. “You are all graduate students, so you think you know everything there is to know, but there is probably a lot you do not… things other instructors will not tell you because they do not think they are important. But they are. Vastly important.”

He opened the first slide, an overhead view of the pyramids. “But before we get to that, I want you to pay particular attention to the Queen’s Pyramids. These smaller structures surrounding the Pyramid of Khufu are like remoras on sharks. In and of themselves they are nothing special, at least not in comparison to the pyramids, and yet their proximity alone makes them worthy of study.”

He brought up a view that accentuated the difference in size between the Queen’s Pyramids and the Great Pyramid. “As you can see, these were not built by the same people, certainly not contemporaries of each other. The construction of the Queen’s Pyramids is so shoddy that it requires a staggering absence of intelligence to make such a leap. No joke, you must have borderline dementia to accept such a ridiculous hypothesis.”

Already three people in the back were gathering their stuff. Wörtlich wasn’t going to stop them. If their minds couldn’t take such a basic challenge, they weren’t worth his time.

“These minor pyramids all contain mummies-or rather, they did before grave robbers got to them. What I find most interesting, though, is that the main pyramids did not. Contain mummies, that is. There is very little evidence to suggest that.”

He changed slides again, but before he could return to his notes, he heard a voice from the front row.

“But isn’t that why the Egyptians built the pyramids in the first place? For burial?”

Surprised, Wörtlich glanced over the lectern and eyed the few students staring back at him. One of them raised her hand. She was an American; her look and accent was unmistakable.

“For one thing,” Wörtlich mused, “I do not accept the premise of your question.”

“That the pyramids were intended for burial?”

“Obviously. But what I mean is, the Egyptians did not build the pyramids.”

Skepticism blanketed the room in an uncomfortable silence, but it was nothing he hadn’t experienced a hundred times before.

Once again, the student put in her two cents. “Forgive me, sir, but that’s… well, that’s preposterous.”

“You are forgiven.”

“What he means,” said another student, a man, “is that the Egyptians made the Jews build them.”

Wörtlich furrowed his brow. “No, that is not what I mean, but I appreciate you putting words in my mouth. Now, I am sorry to contradict your eighth grade history textbooks, but this is a center for higher learning. If you want me to stand here and contribute to one of the longest lasting and most ridiculous lies perpetrated by modern academia-well, I regret you will have to go somewhere else for that. I hear Professor Gingrich hosts an excellent class on Fridays. If, however, you are interested in expanding your minds and hearing what I have to say, then by all means, pay attention.”

He replaced the slide with a profile shot of the Great Pyramid. In the margins, he had scribbled dimensions and proportions.

“In case none of you have seen it for yourselves-and I suggest you get around to it-the Great Pyramid is monstrous. Its base alone covers thirteen acres. It contains 2.3 million stone blocks, each weighing about two and a half tons. In fact, there are a few granite blocks higher in the pyramid structure that weigh over a hundred tons. Do not ask me how they got them up there; that is a question for much later. In any event, it is a hell of a lot of stone.”

He looked squarely at the American student. “If you need a point of reference, that’s enough stone to build a six-foot wall all the way from New York to Los Angeles.”

The student shrugged. “Couldn’t they have built ramps to get the blocks up?”

“Or a pulley system,” another suggested. “One of our professors even theorized that they might have built it from the inside out.”

Wörtlich nodded to the second student for at least doing her homework. “Well, certainly. I suppose those theories might be possible. But what traditional sources do not often admit is that for the Great Pyramid to have been built and completed during the timeframe suggested, the reign of Pharaoh Khufu, workers would have had to move one and half stone blocks into place every hour for twenty-three years, without stopping for nights, weekends, or bathroom breaks. And remember just how heavy they were. Still are, actually.”

“It could have happened. There were thousands of slaves.”

“Sure! Absolutely it could have happened. Let us consider for a moment that you are right. Also consider that the pyramids embody such a wealth of mathematical know-how and precision that its builders would have needed wisdom akin to the knowledge we have today.”

“The Egyptians of that period operated at the height of ancient civilization, didn’t they?” someone asked.

“That is highly arguable. But it is good of you to give them the benefit of the doubt. Let us look at some specifics now, so that you, all of you, can judge for yourselves. Begin with the impressive fact that the pyramid’s base is a perfect square with right angles accurate to one-twentieth of a degree. That is very precise. Also bear in mind that the sides of the pyramid, perfect equilateral triangles, face exactly north, south, east, and west. And I mean exactly. Now, if we take the Hebrew cubit to be 25.025 inches, then astonishingly we find that the length of each side of the base is 365.2422 cubits. Does that number sound familiar to anyone?”

Wörtlich gave them a chance to weigh in. Truth be told, he was delighted that this group at least had the gumption to speak up.

“That’s about the same number of days in a year,” someone answered.

“No,” Wörtlich said forcefully. “It is the precise number of days in a year, including the fraction that accounts for leap years. These builders placed a premium on precision, no? Is any of this starting to sound unlikely? In case there are any skeptics left in the room, and there always are, the numbers get even more interesting. Very juicy. If we multiply twice the length of a side, at the base, by the total height, at the apex-which is 232.52 cubits-we get pi. To within five decimal places! I must say, that is not bad for six-thousand-year-old Egyptians.”

“Okay, I get it,” the first student admitted. “It’s weird.”

Wörtlich rubbed his hands together excitedly. “And just to, how do you say, “make the deal sweet,’ bear in mind that the Great Pyramid stands at the precise center of the world, longitudinally between the west coast of Mexico and the east coast of China, and latitudinally between the northernmost coast of Norway and the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. The Egyptians could not possibly have made such a calculation, what with not having discovered the existence of the Far East or the Americas. You cannot make this stuff up. If the Egyptians were so damned precise, why did the Queen’s Pyramids cave in on themselves after a few centuries while the greater pyramids continue to stand after several millennia?

“Now, Professor Gingrich and most of his peers would chalk all this up to coincidence, one piled upon another. But since I actually understand a thing or two about math, I know better. The odds of that happening are astronomical. I mean, truly and unfathomably massive.”

When he paused, the class was silent. Wörtlich was pleased to note that he hadn’t lost any more people since the beginning of his tirade. He couldn’t help but smile. He hid it by looking down and changing the slide again.

“So, to summarize what you have just heard, these builders had access to knowledge beyond the scope of their worldview. They somehow intuited that the planet was a globe, flattened at the poles, and also seemed to know its rate of rotation, not to mention the 23.5 degree tilt of its axis. And of course, they knew the precise number of days required for the Earth to orbit the sun. But I am sure all that is coincidental. After all, the Egyptians just barely had a firm grasp on the wheel.”

He returned the slide to the opening photo and waited for the inevitable response. Sure enough, they didn’t disappoint.

“So who did build the pyramids?”

Wörtlich smiled crookedly and closed the lid of his laptop.

“Finally, a good question.”

* * *

If you like what you’ve read so far, please visit our Amazon page and pick up a copy today (click here). You can also visit our official website. Happy holidays to all!