Guest Post by John D. Payne

I first learned about terrorism from fiction. My introduction may have come sitting on the couch with my dad, cheering as Chuck Norris shot motorcycle missiles at Arab stereotypes in Delta Force. Or it might have been playing with my G.I. Joes, re-enacting their heroic efforts to defeat Cobra, “a ruthless terrorist organization determined to rule the world.”

But my conscious, academic study of terrorism didn’t start until September 11th, 2001. That morning, I was a graduate student at MIT, on my way to my job as a TA in an American Foreign Policy class. People around me were talking about some accident or catastrophe. I stopped in front of the window of a sports bar in Central Square and saw a TV with video of smoke pouring out a skyscraper in what looked like New York City. One of the little crowd gathered there to watch said there had been a plane crash.

When I got to class, I learned a little more. The second plane had hit the World Trade Center. This was deliberate. Someone had attacked us. I spent much of the rest of the day trying to reach my sister and her family in Manhattan. That night I sat up with my roommates, all grad students like me, talking about what had happened, what it meant, and what we were going to do about it.

Today, I am an Assistant Professor of Security Studies in the College of Criminal Justice at Sam Houston State University. When I am not writing about princesses, unicorns, and dragons, I teach classes (mostly graduate) about terrorism, weapons of mass destruction, and homeland security.

Along the way, I’ve learned a few things about terrorism that are quite a bit different than what I picked up from TV, books, comics, movies, and popular culture.

Here are ten.

1) Unlike Cobra Commander, Dr. Evil, and other cartoonishly villainous masterminds, the leaders of terrorist organizations don’t want to rule the world. Personal ambition doesn’t drive them. They have causes they believe in, people they consider to be their constituents (whether or not those people actually see themselves that way). In the words of noted terrorism scholar Bruce Hoffman, terrorists are altruists. They do what they do because they want to help someone or something greater than themselves.

2) Terrorism isn’t new. It didn’t start on 9/11, or in 1995 at the federal building in Oklahoma City, or in 1979 when students in Tehran took 52 Americans hostage– or whatever your generational touchstone is. US President William McKinley was assassinated by a terrorist in 1901. And if we really want to turn back the clock, in the first century AD a group of Jews resisted Roman rule by knifing people in public places, which looks quite a bit like modern terrorism. Learning about terrorism (and counter-terrorism) in the past might help us make better policy for the future

3) Terrorism isn’t about expensive, high-tech super weapons like the ones Destro invented for Cobra. It’s mostly low-tech and run on a shoestring budget. Consider al Qaeda, one of the best-funded and most sophisticated terrorist groups of all time. The key to the success of their attacks on September 11th was doing something surprising with ordinary things like box cutters and airplane tickets.

4) Likewise, counter-terrorism isn’t all about action heroes like Jack Bauer or James Bond equipped with amazing gadgets like laser watches. Most of our defense against terrorism is just regular people living their normal lives, like the airline passengers who noticed that Richard Reid’s strange behavior and prevented him from setting off the bomb in his shoes. It’s a lot less Real American Hero and a lot more If You See Something, Say Something.

5) Although individual terrorists might take actions that look very dangerous, terrorist groups are often cautious and risk-averse, particularly as regards new methods or weapons. They generally don’t have spare personnel they can afford to lose in experimenting, so they do what they have seen other terrorist groups do. This also means that once an innovation proves effective (like suicide attacks), it spreads rapidly.

6) With some exceptions (*cough* ISIS *cough*), terrorist organizations are not staffed by sadistic maniacs who kill for no reason. The Dark Knight is often seen as a parable about terrorism, but in real life you don’t want to work with someone like the Joker, even if your job is creating violent spectacle. The operatives who carry out suicide attacks are often referred to by terrorists as “human bombs,” and just like any weapon you want it to be as predictable and dependable as possible.

7) Not all terrorists are motivated by religion. In the twentieth century, religious terrorists were clearly in the minority, and even today scholars such as Robert Pape argue that many terrorist organizations we consider to be religious have ideologies that are more about nationalism and resistance to foreign occupation. We can also look at explicitly non-religious or atheistic terrorist groups, such as the LTTE (or Tamil Tigers) who have been carried out long campaigns of suicide attacks. Their operatives weren’t hoping for a better afterlife, they wanted to bring honor to their families, victory for their organization, and freedom to their nation in this life. It’s easy to dismiss the idea of negotiation when we imagine that we’re dealing with ineffable, otherworldly motives, but terrorists’ grievances are usually more grounded. (Not always, though. See: Aum Shinrikyo, etc.

8) Building a profile of terrorists is really tough. Part of the reason is that life is, naturally, more complicated than fiction. And part of the reason is that terrorist organizations are trying to subvert our expectations by recruiting operatives who don’t fit our profiles. The PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party) in the 1990s had a lot of success with female suicide attackers, because that’s not what the Turks expected. Al Qaeda in Iraq (forerunner to today’s ISIS) strapped semtex vests onto mentally handicapped people and children and detonated them remotely as they approached crowded security checkpoints, because it’s so horrible you can’t believe anyone would do that. This is asymmetric warfare, and they know the only way to win is by breaking the rules. So we have to expect the unexpected, which is easier said than done.

9) Killing the leaders of terrorist organizations doesn’t end the problem. Now don’t get me wrong. When I heard the news that Bin Laden was dead, I opened my window, hung out my American flag, turned up my happiest music as loud as it would go, and danced with joy. But one death, no matter how well deserved, didn’t make al Qaeda go away, didn’t make their supporters and sympathizers go away, didn’t make our problems go away. True, al Qaeda is less effective than it once was. But we still have ISIS, lone wolf attacks, mass shootings, etc. We don’t get to ride off into the sunset and roll credits. Terrorism, like crime, and like poverty, will probably always be with us.

10) Fighting terrorism isn’t hopeless. Terrorists don’t always win. In fact, it’s pretty rare that they achieve their ultimate goals. In the two decades after the end of World War II, there were a number of states (such as Algeria and Israel) that won their independence from colonial powers (such as France and Britain), in part through terrorism. But since then it’s hard to point to victory through terrorism. (The Palestinians come closest, but even after decades of struggle they still don’t have a truly independent, fully functional state of their own.) Most terrorist groups fail and disappear. Sometimes they run out of money, or their leaders are all killed or incarcerated, or they just can’t find people willing to fight for them any more.

In the long run, the ‘war on terrorism’ is not about bombs and guns. It’s about ideas, and about will. It’s about hearts and minds. So every one of us is part of this. Just by living your life the way you think is best, by proclaiming your cherished ideals freely and openly and without fear, you’re striking a blow in this war. Keep it up.

John D. Payne lives under several feet of water in the flooded-out ruin once known as Houston, Texas. He is currently undergoing nanobot-assisted gene therapy to develop gills so he can keep up with his alluring mermaid wife and their two soggy little boys. His hobbies include swimming, sailing, diving for treasure, and fending off pirates.

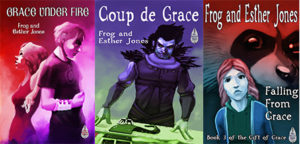

John’s debut novel, The Crown and the Dragon, was published by WordFire Press. His stories can also be found in magazines and anthologies such as Leading Edge, Tides of Impossibility: A Fantasy Anthology from the Houston Writers Guild, and Game of Horns: A Red Unicorn Anthology.

For news and updates, follow John on Twitter (@jdp_writes) or read his blog at http://johndpayne.com.