A guest post by Scott Lee.

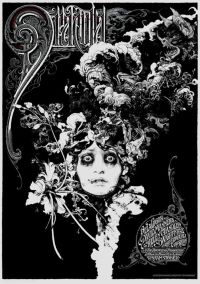

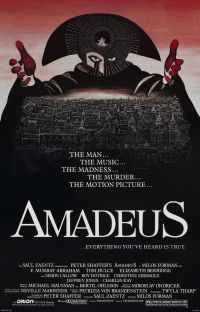

The central theme of 1985 Best-Picture winner Amadeus is the contrast between the sublimity of art created by God-given genius, and the all-too human person through whom the talent is expressed. This requires the film to first portray Mozart as a disgusting, vulgar, immature mismatch for the easy, perfect elegance of his music, and then, in the course of the story’s development to redeem him. The film makes several simple, brilliantly executed moves to bring this about. (1) It establishes Salieri as a sympathetic character for the audience to identify with so they don’t lose interest waiting for Mozart to grow more likable. (2) It lays seeds for the transfer of audience sympathy to Mozart even while explicitly establishing the more disgusting aspects of his character. (3) It moves Salieri on an opposite track, darkening him as Mozart is ennobled. Mozart becomes a maligned-if crass-innocent; Salieri, a literally satanic figure.

The central theme of 1985 Best-Picture winner Amadeus is the contrast between the sublimity of art created by God-given genius, and the all-too human person through whom the talent is expressed. This requires the film to first portray Mozart as a disgusting, vulgar, immature mismatch for the easy, perfect elegance of his music, and then, in the course of the story’s development to redeem him. The film makes several simple, brilliantly executed moves to bring this about. (1) It establishes Salieri as a sympathetic character for the audience to identify with so they don’t lose interest waiting for Mozart to grow more likable. (2) It lays seeds for the transfer of audience sympathy to Mozart even while explicitly establishing the more disgusting aspects of his character. (3) It moves Salieri on an opposite track, darkening him as Mozart is ennobled. Mozart becomes a maligned-if crass-innocent; Salieri, a literally satanic figure.

The audience is introduced to the suffering, forgotten Salieri before the end of the first shot. He cries out for forgiveness. He attempts suicide and is committed to a sanitarium. He proves to have been completely forgotten in his own land despite a life as a public figure. Finally, he has been eclipsed by Mozart, a man he considers his chief rival, and an immature, disgusting person.

This opening shows Salieri suffering profoundly for no apparent reason. It appears to demonstrate his sanity by comparison with other inmates of the sanitarium and demonstrates his sincerity by making his tale a confession to a visiting Priest. This firmly places the viewer’s sympathy with Salieri as the film begins.

Still, the seeds for a transfer of sympathy to Mozart are present. Mozart is the better known name. Our sympathies naturally fall with those we know. While no one living in the twentieth century can claim to know Mozart personally, we know his music and acknowledge him a towering musical talent. Furthermore, Salieri is shown attempting suicide which must occasion some doubt in the audience about his mental stability.

When Mozart appears, he is revealed as extraordinarily immature and vulgar, and completely unaware of social norms. His patron the Archbishop of Salzburg calls him a spoiled, arrogant brat. Attending a court function he disappears, chasing a young lady, swearing at her, and making vulgar sexual suggestions replete with middle-school bodily function vulgarity. He appears first to Salieri and the audience as a nameless “creature” only to be revealed as Mozart by ensuing dialog. The film leaves viewers appalled, having demonstrated the refined, elevated behavior of others at the concert, and having suggested that Mozart’s appearance and behavior would echo the heavenly elegance of his music. We are shocked along with Salieri. Salieri, who has pledged his industry, chastity, and humility to God, appears to great advantage next to Mozart. He seems everything expected of the composer of Mozart’s music: refined, poised, polite, and elegant, with an accomplished social grace.

Mozart’s next appearance is his first audience with Emperor Joseph II. He proves arrogant and condescending, and continues to be gratingly socially awkward. His brashness is matched by his talent, giving some partial justification of for his behavior, but the audience’s sympathy remains firmly with Salieri, whom Mozart indifferently humiliates.

Although still unlikable, Mozart is cast as an archetype from American popular myth: the gifted artist challenging tradition. He is placed in the role by the contempt the musical figures of the court show him. The artist in this role doesn’t have to overcome tradition to be heroic, he or she merely has to be shown to be true to their own artistic vision. In addition, our culture’s tendency to forgive the “peccadillos” of gifted artists begins to work in Mozart’s favor. Finally, while the audience still generally forgives Salieri, the doubts planted earlier continue, and his envy and dislike of Mozart are both obviously present and obviously growing, beginning Salieri’s darkening.

Mozart hits rock bottom in the aftermath of his first staged opera at the National Theater. He is caught having cheated on his fiancé with the woman who Salieri has chastely loved. Thus Mozart offends by hurting his naïve fiancé, and, although unknowingly, by acting against Salieri, who holds the audience’s sympathy. The film then demonstrates Mozart’s selfishness yet again, as he stands smiling guiltily and staring after the angry, departing Madame Cavalieri, while his fiancé vainly attempts to draw his attention to her unconscious mother.

With Mozart in the depths of opprobrium and Salieri at his highest estimation, the film begins the transfer of sympathy in earnest. Salieri steadily darkens, resorting to Machiavellian politics, lying to Mozart, posing as his friend and promoter at court while blocking his commissions, performances, etc., and finally plotting to murder him and steal credit for his work, While Mozart becomes increasingly sympathetic. His obnoxious behavior lessens. His laugh, a high pitched, animal’s bray that emphasizes his social awkwardness, disappears, only reappearing as a sign of growing illness and insanity. Despite Mozart’a apparent laziness, he is proven by Salieri’s own spy to be tremendously industrious in his work on his compositions. He proves loving and faithful to his wife, and increasingly more conservative in dress. His household is shown in slow dissolution, dropping from prestige into poverty as the result of Salieri’s hidden machinations. His immaturity appears increasingly innocent in comparison with Salieri’s increasingly malicious actions. His health deteriorates. His role as embodiment of common, democratic tastes is highlighted, while Salieri becomes the embodiment of authoritarian tradition. Finally, Mozart, lying fatally ill in his bed as Salieri pushes forward with his murderous plan, asks Salieri’s forgiveness for having thought ill of him. In return Salieri admits honest admiration and claims false affection, then insists that Mozart continue the composing effort that is killing him.

In a final shot at Salieri, the film returns to the sanitarium for the conclusion, where Salieri gloats about his victory over God through Mozart’s murder, proclaims himself the patron saint of mediocrities, and is wheeled through the sanitarium “absolving” the imbecilic inmates of their flaws and failings while a voice over of distinctive braying laughter literally gives Mozart the last laugh.

This is not to say the film presents a Christmas Carol style redemption of Mozart. Mozart fails to provide for his family. His wife abandons him for a time in the final act of the film, because he cannot resist the urge to slip off to drink and party. His drinking continually increases throughout the film, and his dependency on various unidentified medicines is explicitly mentioned. He has moments where he ignores his family in favor of his music. His tremendous self-confidence never lessens. Mozart is no Ebeneezer Scrooge, transformed overnight, or indeed even over years, into a perfectly virtuous saint. He remains to the end a vulgar man gifted with transcendent musical talent.

Amadeus beautifully makes a delicate storytelling move-choosing a protagonist who is initially flawed and unlikable and redeeming him in the eyes of the audience, transferring to him the audience’s sympathy and trust mid-story while never denying his essential character with its already established flaws. It accomplishes this by presenting Salieri to hold the sympathy and interest of the audience while establishing Mozart’s all too human character, and then slowly darkening him, even as Mozart’s own suffering and talent lead to his redemption.

* * *

Writer, teacher, director, actor, husband, and father, Scott Lee has written stories and poetry since he learned to hold a pencil. His short story collection Singular Visions (a masters thesis written at CSU-Pueblo), is available through Proquest. He has also published in CSU-Pueblo’s Tempered Steel, and blogs at http://7worlds.tumblr.com