A guest post by Michael A. Rothman.

For a fantasy writer, it’s very convenient to create your own world – because you follow the rules that you set. Much like the famous Twilight Zone saying, you control the horizontal and vertical.

However, what if you want to embark on a journey that isn’t quite set in the mundane world you’re familiar with, yet you might be exploring some of our world’s mysticism? Things like numerology, religion, and legends are all fodder for creative authors to take advantage of.

Why would someone choose to dive into what is essentially someone else’s world? Use its characters and storylines?

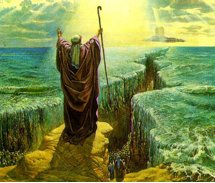

The answer is rather simple – people are already familiar with the beliefs of certain religions. That being said, if your story relates in some way to something familiar, you’ll have a premade audience that will instantly relate in some fashion to your work. Think about it. How many people are familiar with the parting of a particular sea, or the turning of water into wine?

These images are only the beginning, consider other concepts that have been leveraged such as fortunetelling or numerology. In the case of numerology, Dan Brown in the oft-cited bestseller, The Da Vinci Code, uses numeric sequences as clues. He poses many what-if’s that people could go ahead and investigate on their own.

In fact, I just recently finished a manuscript that leverages numerological concepts that follow both a religious and numerological theme. The earliest forms of the bible were written in Aramaic (same lettering system as Hebrew). From this, a numbering system that assigned numbers to letters and words was formed and is oftentimes referred to as gematria. Many studies associated with the bible and its hidden meanings use gematria as a form of numerology. An example of such a thing would be where I use an upcoming villain’s name as a code. His name is Bedsem. It’s a play on words in another language, but suffice it to say that I’ve used the gematria system to associate a numeric value to it. One that people might recognize with a simple illustration.

Yes, I’m guilty as charged. I’ve crossed several genres of religion and “sciences” to associated my villain’s name with what is oftentimes posed as the ultimate villain.

Consider that with numerology, you have the ability to pose many “what if” type of questions to the reader. Take certain “coincidences” in the world and make them go “hmm”.

A word of caution, though. Some people might take offense.

Let’s face it, as authors, we will inevitably write something that people will take offense with. I recall having a scene in one of my earlier books where I had two twelve-year-olds holding hands when one of them decides to give the other a kiss on the cheek.

Wholesome, right? Not a big deal, you’d think?

Well 99% of the responses came back on stating how refreshing and wholesome the book was and how nice it was to have something that was “safe” for the kids to read, yet was an epic fantasy. I only mention this because I got one or two comments that inevitably crucified me (ok, maybe poor choice of words considering context) because I was treating kids as sexual objects who shouldn’t look at each other that way. And to think most people don’t believe we live in a puritanical society. Hah!

When you begin to leverage certain things that people might consider a pseudo-science, you might not get too many critics – unless you’ve botched up your facts. However, once you dive into religion or certain cultural affectation or historical references, that’s when the people who take offense can most certainly come out.

For instance, Salman Rusdie wrote a book called The Satanic Verses. It won many prizes and was critically acclaimed by the literary establishment. All good things. Good until such time as some very conservative followers of a particular religion took great offense. Since the book does touch on one of the prophets from this religion, there were those in the conservative community that didn’t appreciate the way their prophet had been characterized. Given this belief that their religion was being assaulted, there were calls for the author to be killed.

Needless to say, this is the extreme of such possibilities – but when you leverage the topic of religion, it needs to be with both eyes open. Understand how others would appreciate your work or possibly misunderstand your intent.

I’ve spent years informally studying religion, numerology, and related topics – so I’ve been cautious about introducing these things. Nonetheless, these are tools in an author’s toolbox that are easy to deploy, and they can be a powerful draw to an audience that is a match for your subject matter.

***

Mike has had a long career as an engineer and has well over 200 issued patents under his name spanning all topics across the technology spectrum. He’s traveled extensively and has been stationed in many different locations across the world. In the last fifteen years or so, much of his writing has been relegated to technical books and technical magazine articles.

It was only a handful of years ago that his foray into epic fantasy started, but Mike is a pretty quick study. He’s completed a trilogy, has a prequel under consideration with editors, and is actively working on another series.

In the meantime, if you want to see his ramblings, he lurks in the following social media portals: Twitter – @MichaelARothman, Facebook, his blog, and his books.