I’m no authority on small publishers. Or big ones.

Oh, you aren’t either?

Awesome! Let’s learn together.

Let’s start from the beginning. What are the differences between big and small presses? What does it mean for you as a writer? You’ll have to do research on specific presses, but usually, a larger publisher will have a sizable staff with different departments that can see to the publication of your book from beginning to end, including marketing and advertising. Does this mean small presses don’t have these? Not necessarily. Many small presses have all of that as well, but some may not have as large of budgets to spend on marketing and advertising, for example. Some may not have the distribution that bigger publishers have. Each publisher is different, and you’ll need to research each you are interested in individually to see what they offer.

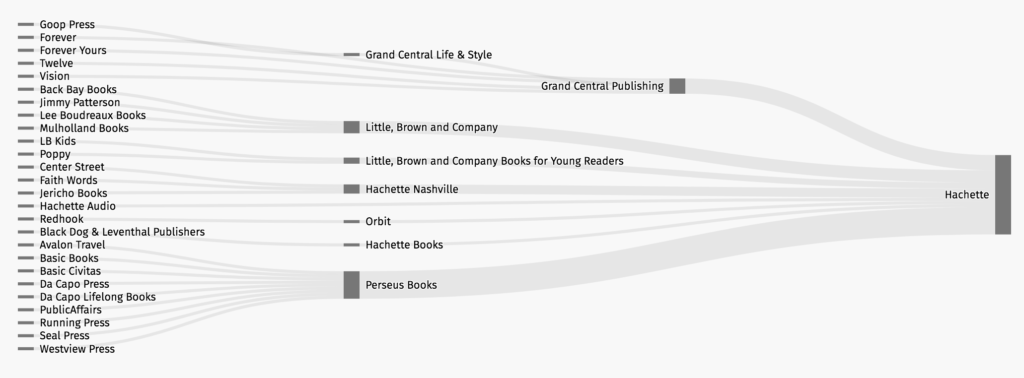

First, how can you determine if a publisher is a small or large press? An imprint? Check out this incredibly handy chart made just one year ago that shows the big publishers and their imprints: https://almossawi.com/big-five-publishers/.

Here’s an example of one section of the chart:

As you can see from just this branch, the chart is comprehensive, and is a good resource if you want to find an imprint of any of the top (and largest) publishers.

As you can see from just this branch, the chart is comprehensive, and is a good resource if you want to find an imprint of any of the top (and largest) publishers.

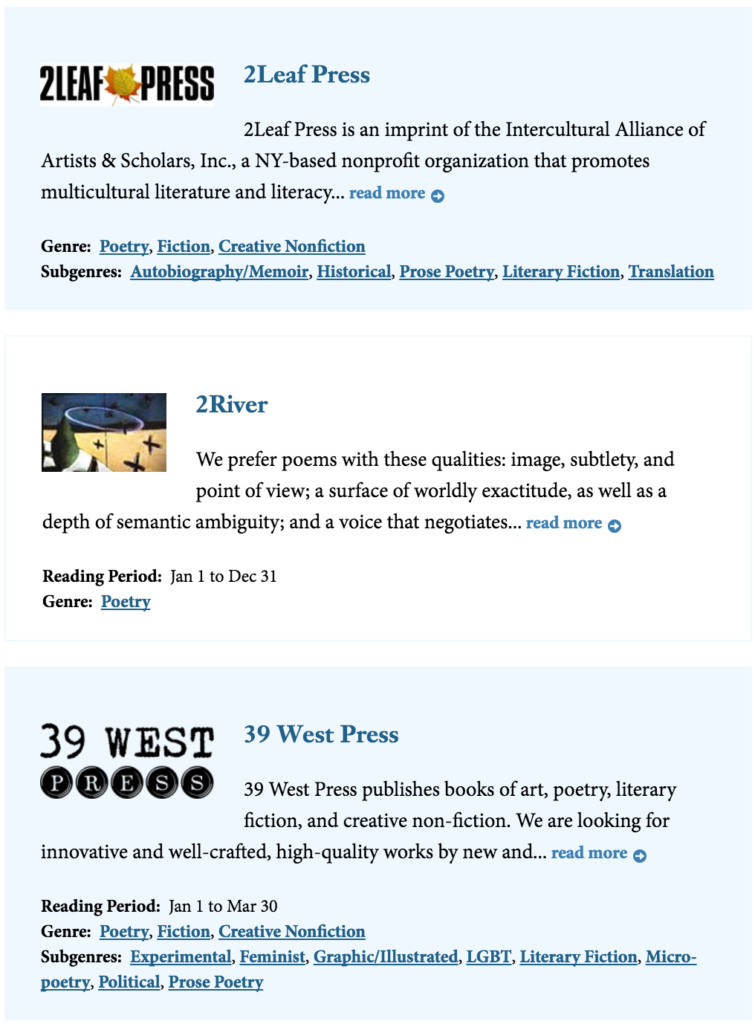

If you’ve established that the publisher you’re looking for isn’t an imprint, here’s a fantastic resource in Poets & Writers for almost every small press: https://www.pw.org/small_presses.

If you’ve established that the publisher you’re looking for isn’t an imprint, here’s a fantastic resource in Poets & Writers for almost every small press: https://www.pw.org/small_presses.

You’ll notice that each publisher has a brief description, their reading period dates, which genre(s) they publish, and any sub-genres. Most smaller publishers should be listed in this comprehensive database, and will include a link to their websites. Read every word of the publisher’s website. I mean it! Every. Single. Word. Take a day or seven to consider if the publisher would be a good fit for you and your work.

Compile a list of the small presses that you think would be the best fit.

Once you’ve considered a number of publishers, small and large and otherwise, what exactly should you be looking for? What questions should you be asking yourself, and what information should you be looking for?

The Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America website has an entire page dedicated to information about small presses, including warning signs one should know to look out for when considering a smaller press. While it’s a lot of information, it’s well worth the read and worth bookmarking for future reference: http://www.sfwa.org/other-resources/for-authors/writer-beware/small/. At the end of the article, SFWA lists a number of additional resources.

The Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers of America website has an entire page dedicated to information about small presses, including warning signs one should know to look out for when considering a smaller press. While it’s a lot of information, it’s well worth the read and worth bookmarking for future reference: http://www.sfwa.org/other-resources/for-authors/writer-beware/small/. At the end of the article, SFWA lists a number of additional resources.

Which is the best publisher?

That, my friend, is up to your own evaluation of your writing, your career goals, and the publisher that can best help you achieve your goals. It’s all a matter of research and evaluation. Happy researching and evaluating!

As my fellow Fictorians are showing you so far this month, there are many ways to set yourself apart as a writer. In my mind, the most memorable way to set yourself apart is voice, to the surprise of no one. In past posts, I’ve highlighted how you might

As my fellow Fictorians are showing you so far this month, there are many ways to set yourself apart as a writer. In my mind, the most memorable way to set yourself apart is voice, to the surprise of no one. In past posts, I’ve highlighted how you might

Robert Kirkman

Robert Kirkman I would be remiss if I didn’t point out an author I’ve mentioned many times in my Fictorians posts who is, in my mind, the king of grammatical voicing:

I would be remiss if I didn’t point out an author I’ve mentioned many times in my Fictorians posts who is, in my mind, the king of grammatical voicing:

In the first half of Gillian Flynn’s bestseller Gone Girl, I was amazed. Flynn’s ability to communicate small issues in a marriage, how they can appear and fester just under the surface, was revelatory to me. I sure didn’t pick up Gone Girl expecting such an accurate and subtle commentary on American marriage and the differences between blue-collar and white-collar partner philosophies.

In the first half of Gillian Flynn’s bestseller Gone Girl, I was amazed. Flynn’s ability to communicate small issues in a marriage, how they can appear and fester just under the surface, was revelatory to me. I sure didn’t pick up Gone Girl expecting such an accurate and subtle commentary on American marriage and the differences between blue-collar and white-collar partner philosophies. Similarly, in Flynn’s novella The Grownup, the reader is presented with an anti-hero that, at first blush, seems honest and straight forward about who she is: a fake psychic. I’ll not mention her former job so you’re surprised when you read the short story yourself (I’ll just say this: the first two lines of the story are some of the best opening lines I’ve ever read. Talk about a hook! Winky wink). Now, as we, the readers, follow this opportunistic woman, we fall into a haunted house/evil stepson-type scenario. Nothing too surprising here – they are common horror movie tropes. And our protagonist, although a con artist of sorts, still has some admirable attributes, and it’s easy to slip into the story from her perspective. We’re even on her side. (Big spoiler here, so skip to the next paragraph if you want to read this story.) We’re on her side, that is, until we realize too late that she’s not an anti-hero – she’s the villain, and became so under our very noses. And this is Flynn’s trademark. Unreliable narrators to an extreme. Characters that seem like unreliable narrators and anti-heroes who become the villains before the reader can put two and two together.

Similarly, in Flynn’s novella The Grownup, the reader is presented with an anti-hero that, at first blush, seems honest and straight forward about who she is: a fake psychic. I’ll not mention her former job so you’re surprised when you read the short story yourself (I’ll just say this: the first two lines of the story are some of the best opening lines I’ve ever read. Talk about a hook! Winky wink). Now, as we, the readers, follow this opportunistic woman, we fall into a haunted house/evil stepson-type scenario. Nothing too surprising here – they are common horror movie tropes. And our protagonist, although a con artist of sorts, still has some admirable attributes, and it’s easy to slip into the story from her perspective. We’re even on her side. (Big spoiler here, so skip to the next paragraph if you want to read this story.) We’re on her side, that is, until we realize too late that she’s not an anti-hero – she’s the villain, and became so under our very noses. And this is Flynn’s trademark. Unreliable narrators to an extreme. Characters that seem like unreliable narrators and anti-heroes who become the villains before the reader can put two and two together. When it comes to famous friendships, the one that first comes to mind is the bond between C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Their friendship developed through their writing group, The Inklings, which met in a pub called The Eagle and Child, or as they affectionately called it, The Bird and Baby. Over years of critiquing and beers, a number of the Inklings went on to be published, as well as become some of the most respected authors in history.

When it comes to famous friendships, the one that first comes to mind is the bond between C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Their friendship developed through their writing group, The Inklings, which met in a pub called The Eagle and Child, or as they affectionately called it, The Bird and Baby. Over years of critiquing and beers, a number of the Inklings went on to be published, as well as become some of the most respected authors in history. In college, I was fortunate enough to take a J.R.R. Tolkien class from one of the most renowned C.S. Lewis scholars in the world, Diana Glyer. Naturally her studies of Lewis led her to the study of Tolkien as well. Diana Glyer recently released the book

In college, I was fortunate enough to take a J.R.R. Tolkien class from one of the most renowned C.S. Lewis scholars in the world, Diana Glyer. Naturally her studies of Lewis led her to the study of Tolkien as well. Diana Glyer recently released the book