There are a lot of small presses out there publishing excellent books. Publishing with a small press comes with benefits but also drawbacks, and we’ve had some great posts this month talking about both. As someone who’s sold short stories to anthologies published by a number of small presses, I’ve had some illuminating experiences for both good and bad.

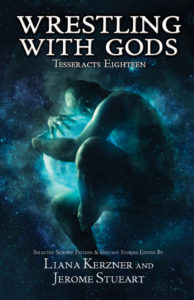

The good: Being published by a small press gave me networking “cred” that self-publishing likely would not have. I’ve run the editorial gauntlet, so to speak, and my stories were chosen to appear in venues such as the Tesseracts anthologies (published by EDGE), Women in Practical Armour (published by Evil Girlfriend Media) and my first sale, the e-book edition of When the Hero Comes Home 2 (published by Dragon Moon Press). These credentials have given me contacts and opportunities that I would not have gotten, or would have been much harder won, if I’d needed to convince those contacts that my self-published work was as good as the work that these presses published.

The bad: Small presses are small, and that means internal issues at the publisher, outside the writer’s control, can have a huge impact. Setting aside cases of deliberate fraud or well-intentioned bumbling: even the most professional of small presses can be vulnerable.

Case in point. I sold a story to an anthology that was going to be published by a small press. Shortly thereafter, the press’s owner (and primary operator) sadly passed away. There was no one to take over ownership of the press and it closed. The anthology went out of print only a few weeks after it first came out when the press closed. I say “out of print,” but in a digital sense…the paper copies had not yet become available.

Fortunately, the anthology was saved when the editor–who had independently published some of her own work–made arrangements that allowed her to publish the anthology as a “Second Edition” under her self-publishing banner. It is now, once again, available in both print and e-book.

It was, however, a reminder to me that even reputable small presses can find themselves struggling when personnel step down. The effects of financial issues, personal issues, and health concerns–all perfectly understandable–are magnified when they affect a small business owner or key staff member and there is no one else willing or able to fill the role.

There have been a number of calls for submissions for anthologies that I would have liked to have been part of, only to have the calls delayed or the anthologies cancelled because of life issues on behalf of the editors and/or publishers. I can count my good fortune that I either had not yet started writing the stories or else was able to adapt them enough to sell them elsewhere.

What does this mean for writers? It is a factor to consider. Can you sell your book or story to a large professional market, or do you need to seek out venues that accept unagented submissions or will consider a revised version of a work that other markets have turned down? Will the credit of passing the small press’s editorial gauntlet reflect well on you as a writer and open up new opportunities, or is it better off to self-publish and keep control of your work? The reputation of the press itself can play a big role. And there is no “one-size-fits-all” answer. There are certain stories written by certain writers at certain stages of their career that will benefit from being published by certain small presses, and there are factors that even the most careful research can’t uncover before a contract is signed. Weigh your options, research to avoid the predators, make your choices, and best of luck.