Since college I’ve been fascinated by culture and society (yes, they’re two different things), as well as the humans who engender both. Granted, it wasn’t fascination enough to get a degree in, but there was interest nonetheless. How each one of us perceives and, ultimately, judges others matters greatly upon the culture in which we were raised. Those we consider our heroes and villains are similarly shaped by our cultural influences.

I feel compelled to mention that I’m about to throw you a curveball or two, so watch out.

In Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained a young slave seeks a reckoning from slave owners and bigots alike as gateway to reuniting with his beloved. Django kills just about every white man depicted in the film, and American as well as international audiences cheered the hero on to the tune of $465 million in worldwide box office sales. Django Unchained is, to date, Tarantino’s highest grossing film.

I think it’s safe to say that as Americans we embrace journeys of the enslaved slipping their bonds and exacting retribution against their enslavers. We’re sort of hardwired for it in part because of our own cultural heritage. We refer to that heritage affectionately as the American Revolution. The British at the time, however, considered it a less-than-convenient and very costly insurrection.

Perspective is everything, and I think it’s also safe to say that American audiences of today have a heightened sense of guilt-yes, I used that word-regarding the treatment of African Americans from the time of this nation’s incept all the way to modern day. There has been and continues to be a struggle towards both acknowledging and even correcting the treatment of minorities throughout our own past.

But consider this: how well would Tarantino’s Oscar-winning screenplay have been received in 1952? Without a doubt it never would have seen the light of day, and it’s writer probably would have been plopped down squarely in front of a McCarthy trial. I think it’s important to point out here that in March of 2004, Dave Chappelle filmed a sketch where the black “Time Haters” return to the 19th century and shoot a white slave owner holding a whip. The episode was censored, and in the DVD collection sold later, Chappelle lamented, “Apparently shooting a slave master isn’t funny to anybody but me and Neil-if I could I’d do it every episode!” That was only nine years ago.

Cultural perspective. It waxes and wanes like a storm-tossed shoreline.

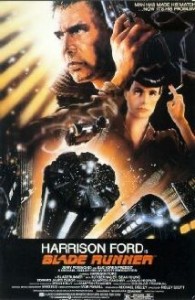

Now let me describe a screenplay that is actually quite similar to Tarantino’s but which most audiences interpreted as being its exact opposite. I’ll give you a few clues. The film was released in 1982 and is still considered by many as a science fiction classic. In this screenplay an Officer of the Law is retained to hunt down and execute four super-human rebels who are loose in the city and murdering law abiding citizens. The officer is generally considered to be both the protagonist and the hero of the film. By the end of it the Officer is victorious and all four murderers are dead. And yes, this screenplay is very similar to Django Unchained.

Confused yet?

What I find interesting is that I have yet to discuss this subject with anyone who didn’t consider Rick Deckard-the Officer of the Law-to be both protagonist and hero. Sure, most people get teary-eyed as Roy Batty gives his famous monologue and dies (after saving the life of his would-be executioner, I might add), but audiences almost universally heralded Deckard as the hero doing the job that had to be done. He’s even rewarded with his own slave girl, namely, Rachel.

Now let me give you my interpretation of the script Ridley Scott wrote. Four slaves created to obey without question and then dutifully die must struggle against insurmountable odds to shatter their bonds. In it they endeavor to find and kill those people responsible for their enslavement as bread crumbs to tracking down their creator and slave master. Their goal is to either achieve the freedom and longevity that has been systematically denied them or put an end to their creator and the cycle of slavery.

Sounds a lot different when I put it that way, doesn’t it?

But that’s not what most people walk away from Blade Runner thinking, is it? Audiences were delighted to see Deckard driving off through the mountains with Rachel, and sure, as a replicant we get a sense of “achieving freedom” for her. I won’t go into the fact that Deckard was, actually, a replicant created to hunt down and kill his fellow slaves. That’s an entirely different diatribe, and one which Scott has admitted to in recent years.

What’s important here is that the hero of Blade Runner is Roy Batty, and the underlying goal inherent in the storyline is his struggle to free his fellow slaves and keep his loved one, Pris, from dying.

How is that so different from Django Unchained?

The answer is, it’s not. But we didn’t look at it that way in 1982, and most still don’t. I had a debate only a few months ago with a writer who insisted that Roy was the villain. He pointed out that Roy was killing people just going about their jobs, killing people who didn’t have any deliberate intention of creating slaves. They were just creating replicants, right? Even just parts of replicants, like their eyes. That makes Roy the bad guy, right? And retirement wasn’t murder, it was the elimination of defective property that was a danger to society.

Yet here we were rooting for Django and not for Roy.

This all boils down to not only who we consider to be us, but who we also consider to be them. Our cultural and societal perspective is practically built upon a foundation of us versus them. That too is hardwired into our consciousness.

So, allow me to suggest that you break out or track down a copy of Blade Runner and watch it with a different perspective. Go into it with the notion that Roy, Pris, Zhora and Leon are slaves, that they are living souls willing to fight for the little bit of freedom and happiness that we all take for granted. And, ironically, consider the implications of another slave–that we identify with–had been created for the sole purpose of hunting them down one-by-one and killing them for the threat to society that they were.

You may walk away with a different take on the movie, particularly now that you’ve (hopefully) seen Django Unchained.

And once you’ve done that, apply it all to your own writing from this day forth.