A guest post by Sherry Peters.

Be sure to read A Mountain of Goals, Part One, published yesterday right here on the Fictorians.

Be sure to read A Mountain of Goals, Part One, published yesterday right here on the Fictorians.

I always knew that if I were ever published, I would do everything I could to make my books succeed. The same is true for self-publishing. I’m not going to do what I did with my previous book, Silencing Your Inner Saboteur, which I gave very little promotion (though I may be stepping that up soon as well), because that book was a bit of an experiment and a useful tool.

Once I made the decision to publish Mabel, I began doing a lot of research on the self-publishing/indie industry. It is my responsibility to make my book succeed. I have no one else to blame. Some days I love it. Some days it is incredibly overwhelming. My to-do lists are pages long every week. I could probably make a book of those alone once they’re all compiled!

Aside from the obvious “write the best damn book possible” advice, building a platform is the main form of advice. Platform means building a mail list, blogging, sending out a regular newsletter, facebooking, tweeting… to paraphrase William Shatner, it should be “all Sherry all the time.” I’m supposed to be super interesting and fun and likeable, and apparently highly opinionated in a likeable fun way. Now, I think I am a likeable person. I’m not sure how interesting I am.

What’s interesting about me? What do readers want to know? I’m not really of the generation that wants to know everything about my favorite author. Just write another book; that’s all I want from them. I don’t follow celebrities, and the only authors I friend on Facebook are the ones I already know personally.

You can get a lot of advice on pricing and giveaways, including free books. I must say, I find this a touch on the offensive side. Not that I’m actually offended by the idea, maybe just hurt or disheartened. I can’t imagine a traditional publisher putting out a book on Amazon for free for a day, or even at $0.99 for a day in the hopes of driving up the sales numbers. It feels like I’m cheapening my work, my product. It may be to my detriment, but I’m not sure I’m going to do that.

I realize that I’m at a disadvantage, putting out Mabel this August. I haven’t finished Book 2 in the series yet (though I’m hard at work on it). And putting out a single book means I don’t have what is called a product “funnel,” where readers can get the first book at a discounted price to lure them into buying the second book. That’s why I’m giving away three Mabel Goldenaxe short stories prior to the release of the novel as an incentive/thank you for signing up for my newsletter.

Promotion doesn’t end there, of course. I printed beautiful postcards (through Vistaprint) with the cover on it, and a “call to action”—for people to go to my website, sign up for my newsletter, and get a story—which I put out at my local convention (Keycon). I’m having my book launch at When Words Collide this August, and I’m going to have one at McNally Robinson Booksellers in Winnipeg.

Promotion, then, is probably the biggest headache which all authors, traditional or indie, have to deal with. That is the reality of the business. Publishers have less and less money to give to it, so we’re doing a lot of the same things. The biggest difference is that traditionally published authors get distribution, and get reviewed by major newspapers (well, they can, if they’re a big enough name, or local, or a specialist). That is to say, most newspapers still won’t consider reviewing a self-published book.

What about the book production? I go for coffee every other week with a friend, usually to a Chapters, and half our time is spent looking at books. I’ve turned this into a great time for surveying what’s out there, what I like, what I don’t, what works and what doesn’t. It’s amazing how many crappy covers there are. And there are some spectacular ones. The artwork matters. It matters. It matters. It matters. So do the interior aesthetics. If the type is too small or too crowded, if it doesn’t feel good in my hand, I don’t pick it up. If the art looks like the pulp editors would have rejected it for being cheesy, I won’t pick it up. If I can’t read the title or the author’s name, I won’t look at it.

There are three main categories for YA covers. Take a look the next time you’re in a bookstore or on the Amazon/Chapters/Barnes & Noble websites. First we have the uber close-up of the face. Usually this means the focus is on the eyes or the lips. Sometimes this pulls out a little further to where we have more of the body, but part is cut out of the frame so it’s only half a face. Sometimes it’s just the torso to show off a plaid pleated skirt (a lot of pleated skirts on headless girls). These are usually in the genre of what used to be called “chick-lit.” I’m not sure what they would be called now.

Then we have the full body, most often with the back to the reader, the head in half-turn. This fits mainly into the urban fantasy or paranormal romance category. But not always. There are some like this that are much more pure romance, as evidenced by the character on the cover wearing a ball gown of some kind.

And finally, we have the symbol on the cover. I think this was made most popular by The Hunger Games. Divergent is another example of this. We see this much more often in the non-YA books, like the adult editions of the Harry Potter books, and the Game of Thrones books are going the same way.

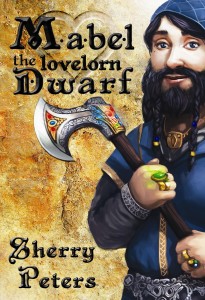

Given the prose style and content of Mabel, I opted for the semi-close-up. I had intended to go with a symbol, but there were already a few books out there with axes on them and while it could be stunning and unique, I couldn’t picture it. So I did my research. I spent days researching fantasy artists, finding out about their work, their rates, etc. To be honest, once I saw Jordy Lakiere’s dwarves, I knew he was the one I wanted. I didn’t think I could afford him, or that he’d want to do a cover for me, but I took a deep breath and e-mailed. Needless to say, it worked out great. I love the Mabel he did for me.

Cover art, in some ways, is just the beginning. I wanted to put out the most professional book I could. And what do traditionally published authors have that indies don’t (besides distribution)? A copyeditor. So I did more research, and I happened to also know a good editor personally, Samantha Beiko. She posted on Facebook that she was looking for freelance editing right when I was looking. Budget, of course, was a consideration, but copyediting was an expense I was willing to pay for. She also did my cover design and the back cover copy.

While the production of the book is well underway (thanks to having done Silencing Your Inner Saboteur, I’m confident in doing the interior layout myself), the promotion is still my biggest mountain to climb. I’d call it a hurdle, but it’s more of a never-ending process. I hope that at some point down the road, I’ll reach a plateau of sorts where, as the gurus keep telling me, promotion will generate itself.

I was going to conclude by saying that I’m off to go learn more about building my platform, but I think I’m going to go work on Mabel, Book 2. That’s one of the working titles. The others are Mabel the Misguided Dwarf—or my personal favorite, Mabel the Mafioso Dwarf. But for now, let’s just call it Mabel, Book 2.

Guest Writer Bio:

Guest Writer Bio: Hailing from Winnipeg, Sherry Peters is a writer and a certified Success Coach for writers specializing in the areas of goal-setting and eliminating writer’s block. She has taught her “Silencing Your Inner Saboteur” workshop online through Savvy Authors, and several Romance Writers of America chapters, and in person at When Words Collide in Calgary and Word on the Water in Kenora. Her book, Silencing Your Inner Saboteur, has sold internationally and has been recommended to graduate students at the University of North Carolina and the University of Winnipeg. Her first novel, a YA fantasy, Mabel the Lovelorn Dwarf, will be available August 2014. She attended the Odyssey Writing Workshop and earned her M.A. in Writing Popular Fiction from Seton Hill University. For more information on Sherry, her workshops, and her coaching, visit her coaching website or her author website.

This was not my plan. A part of me still wants to be rescued from this and put back on the track that was supposed to be. But the more I learn about the business of self-publishing, the more I realize that even authors on the track-that-was-supposed-to-be have to go through much of the same. And I’m a bit of a control freak at times, so being in control of every aspect of publishing my book is fabulous and terrifying at the same time.

This was not my plan. A part of me still wants to be rescued from this and put back on the track that was supposed to be. But the more I learn about the business of self-publishing, the more I realize that even authors on the track-that-was-supposed-to-be have to go through much of the same. And I’m a bit of a control freak at times, so being in control of every aspect of publishing my book is fabulous and terrifying at the same time. Let’s be frank. Writers are sympathetic characters, editors are not. Writers toil in romanticized isolation but get invited to the coolest parties. They create and share every moment of joy and sorrow experienced by not just one character, but by an entire world of their creation. They brainstorm and draft, rewrite and polish, and then one day they mass submit that perfect story to the editorial altars.

Let’s be frank. Writers are sympathetic characters, editors are not. Writers toil in romanticized isolation but get invited to the coolest parties. They create and share every moment of joy and sorrow experienced by not just one character, but by an entire world of their creation. They brainstorm and draft, rewrite and polish, and then one day they mass submit that perfect story to the editorial altars. As a writer, I’ve worked with a variety of editors, good and bad, from newspapers and books to literary and genre magazines. And as an editor, I’ve worked with sci-fi writers and romance novelists, journalists, and poets. There are countless essays about what editors are looking for, what their major peeves are, and how you can improve or kill your chances of getting published. Some of my favorite can be found right here on The Fictorians. After you’re done reading my essay, make it a point to check out Joshua Essoe’s “

As a writer, I’ve worked with a variety of editors, good and bad, from newspapers and books to literary and genre magazines. And as an editor, I’ve worked with sci-fi writers and romance novelists, journalists, and poets. There are countless essays about what editors are looking for, what their major peeves are, and how you can improve or kill your chances of getting published. Some of my favorite can be found right here on The Fictorians. After you’re done reading my essay, make it a point to check out Joshua Essoe’s “ If you’re a writer reading this, think about the last time you asked your friend, husband, wife, or dog to read the latest draft of your story. Did you notice how their eyes darted toward the door in a desperate attempt to escape? Did they sigh? Did they take your pages only to not have read them a month later? Did they say it was nice? Editors will never treat you like that. This bears repeating: editors want to read your work. You are their raison d’être.

If you’re a writer reading this, think about the last time you asked your friend, husband, wife, or dog to read the latest draft of your story. Did you notice how their eyes darted toward the door in a desperate attempt to escape? Did they sigh? Did they take your pages only to not have read them a month later? Did they say it was nice? Editors will never treat you like that. This bears repeating: editors want to read your work. You are their raison d’être. When a form letter goes out, the work that came in most likely was riddled with grammatical and spelling errors, displayed a total disregard of the publication’s submission guidelines, and/or wasn’t even a complete story. The form letter allows the editor to exemplify a level of professionalism with which the writer may not have treated his or her work.

When a form letter goes out, the work that came in most likely was riddled with grammatical and spelling errors, displayed a total disregard of the publication’s submission guidelines, and/or wasn’t even a complete story. The form letter allows the editor to exemplify a level of professionalism with which the writer may not have treated his or her work.