(Guest post from Helen Savore)

Friendship, especially in the form of the companion is a key role in fiction. We’ve spent the whole month talking about the iconic greats, and discovering some new exemplars too. The companion does so much for our protagonist, providing support, knowledge, assistance, even generating sympathy for our readers.

In some stories, they help define the protagonist. Multiple perspectives in a story gives us different takes on a plot, but what about different views of our people? You don’t even need to do this through pov, the friend’s words and action, even filtered through our protagonist, can still provide a rich message to the reader. Sometimes we get so deep into the struggles of our leading person we need that reminder to come up for air and see there might be different takes on this situation.

Friendships are also a great way to introduce characters, either as the story starts, or coming in later. With friendships there’s an assumed history. When written right, it’s clear through every action, every word, every movement. In ensemble pieces you don’t have a lot of time to get to know your characters, so every scene has to do double duty. I’m not just meeting you, I’m learning about other folk too. Think how Danny and Rusty assemble the crew in Ocean’s Eleven. No one says hello. Each approach is unique, showing us their relationships, which teaches us about each of them. As Basher puts it “It’s good to be working with proper villains again.”

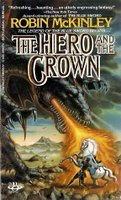

Then there’s the opposite. In a more lonely work, singleton stories, at least one form of companion gives us insight into our protagonist, gives them someone to share with. One of my favorite stories is The Hero and the Crown, but I admit McKinely writes a lonely story. As a classical introvert on the edges of my peer group, Aerin is an attractive character, but I’m not sure this beloved story would be bearable without her beloved Talat. (Don’t you dare tell me horses cannot be friends!) Even though he can’t strictly speak, that horse can communicate. Through his actions, and reactions to Aerin, we come to empathize with this DragonKiller from before the legends.

Another interesting case is the Legend of Zelda franchise. Though wonderfully puzzling and iconic the earliest incarnations didn’t have a lot of story, but this changed over time. With Breath of the Wild’s release my husband and I have been debating what are the best games. As a storyteller, that aspect obviously ranks high for me compared to others (don’t worry, I love my dungeons challenges too), but that lead us to question: what makes the best Zelda story?

Video game characters, are sometimes designed to be a blank slate sometimes to allow the player to become the character more easily. Link is one of our most classic silent protagonists, so without words how do we then empathize with a character? A premise might get us to start reading a story, or playing a game, but it’s the journey of our characters that keeps us going. Yeah Link returns constantly to the main settlement in some games, or passes through different villages and meets folk. However it’s only in the games where he consistently is meeting the same people that we really get a better feel for Link himself, and the struggles of the people Hyrule. We get a better feel of what we’re fighting for, not just to vanquish Ganon once again (because he always comes back!). Where is this stronger than in the stories where he has a companion? The companion serves a game mechanic of assisting the player, but provides us a voice, and an opinion on Link’s actions. It gives us someone to share the journey with.

In developing my own work, Tales of the Faerie Forge, I have races of beings that don’t age. As long as they aren’t broken they’ll continue to live. But I didn’t want them to exist in a perpetual stasis, and part of that was making sure they could continue to grow, and evolve. This meant establishing a culture with changing relationships, since people are so defined by who we are with. This is no pledge to a partner for life. Often it’s a deep friendship, so they form an alloy amidst each other for a time. But it can be reforged with others as they grow

I’ve shared some of mine, but who are your favorite companions in fiction? How do they compliment our protagonists?

***

When it comes to famous friendships, the one that first comes to mind is the bond between C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Their friendship developed through their writing group, The Inklings, which met in a pub called The Eagle and Child, or as they affectionately called it, The Bird and Baby. Over years of critiquing and beers, a number of the Inklings went on to be published, as well as become some of the most respected authors in history.

When it comes to famous friendships, the one that first comes to mind is the bond between C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Their friendship developed through their writing group, The Inklings, which met in a pub called The Eagle and Child, or as they affectionately called it, The Bird and Baby. Over years of critiquing and beers, a number of the Inklings went on to be published, as well as become some of the most respected authors in history. In college, I was fortunate enough to take a J.R.R. Tolkien class from one of the most renowned C.S. Lewis scholars in the world, Diana Glyer. Naturally her studies of Lewis led her to the study of Tolkien as well. Diana Glyer recently released the book

In college, I was fortunate enough to take a J.R.R. Tolkien class from one of the most renowned C.S. Lewis scholars in the world, Diana Glyer. Naturally her studies of Lewis led her to the study of Tolkien as well. Diana Glyer recently released the book