You’ve written several stories and the characters are all beginning to sound the same. How can you mix it up without using the same old characteristics that are embedded in your subconscious?

Try Tarot.

It’s fun and it’s easy.

Although the exact origin of Tarot cards isn’t known, we do know that during the Renaissance the cards were designed to explore archetypal and psychological patterns. For example, death is an archetypal event because it exists in all cultures and a psychological event because of the changes in a phase of life, changing events or people in our lives ,or because of personal emotional changes. Tarot cards are meant to be read on all these levels.

There are too many cards to summarize their individual meanings and the book accompanying the set you use provides that information. The deck I’m using is The Mythic Tarot: A New approach to the Tarot Cards. It was designed with the images of the Greek gods because of their influence on Western society.

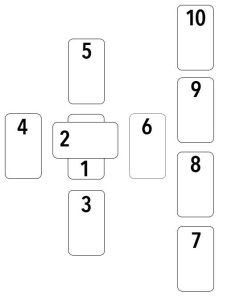

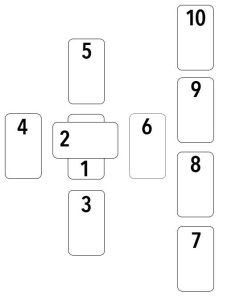

Let’s use the Celtic Cross and Sword Spread. The Cross Spread gives us information about the protagonist while the Sword Spread tells us what lies before our hero. Here’s how it looks:

The position of each card means something specific. There are books and websites which have reams of information on each of these aspects. This version has been grossly simplified for brainstorming purposes.

Now, we need a character and the story premise. Let’s have a hero who must save the world from an evil sorcerer. I know it’s been done a million times before but that’s why it’s a good example about how Tarot can be used to mix it up.

Allan, our hero, lives in the rural Midwest. Life on the prairies is hard but it’s a good community, strong with family values but there are things that make him miserable like his cruel father. The day before an old bookstore is torn down in the neighboring town of 500 people, Allan explores the derelict building and finds a book hidden in a wall. He opens the book, reads a verse out loud and unleashes a sorcerer. His best friend is a girl named Becky.

This exercise is in three parts:

A) What the card’s position means;

B) What the card itself means; and

C) What means for our character.

Cards 1–6 (Cross Spread) tell us about the protagonist.

1A) The Heart of The Matter

This card is the primary focal point for the hero. It focuses on a central issue or a major concern. It may be in the form of a dominant characteristic, a major influence or a basic worry.

1B) Five of Swords

With the capacity to create good or evil fate according to the strength of his beliefs or principles, the hero needs to face his limits to go forward. Doing so will allows him to accept his own destiny and to earn his right to manhood and eventual kingship.

1C) The Meaning

Allan has unleashed a sorcerer who is now on a rampage and that freaks him out completely. After having only read superhero stories and growing up in a rural community, he feels inadequate to the task of stopping the sorcerer. Allan needs to find and bolster his inner strength, overcome fears of inadequacy and step up to the challenge.

2A) The Opposing Factor or Adversary

Literally, as seen on the spread, that which crosses you. This is a contrary element, a complicating factor.

2B) The Hermit

The lesson of time and the limitations of mortal life – a lesson that normally comes with age and experience wherein the hero arrives at maturity, a deep respect for his limitations, and a firm sense of identity.

2C) The Meaning

Allan decides to do something because he’s the only one who can but he isn’t sure of himself, and doesn’t have the confidence to go it alone. For this reason, he seeks help from people he shouldn’t trust.

3A) Crowning Card/ Root Cause

That which hangs over the protagonist in the immediate present. It’s directly under the protagonist. It may be an unconscious influence, a hidden influence, or something from childhood. Whichever it is, it’s the source of the protagonist’s problem.

3B) Eight of Wands

Confidence and new energy is gained after triumphing over obstacles. A period of action after delay or struggle. Travel is implied.

3C) The Meaning

False confidence fills Allan’s head after experiencing a minor success. He now believes he can be the things his domineering father told him he could never be or do. Yet, his underlying fears and his father’s voice in his head undermine him.

4A) The Base of the Matter or the Immediate Past

Something related to the hero’s immediate past such as a belief, an event, an opportunity, a fear, a hope, or something resolved like a task, or unnecessary baggage. It may be an unconscious influence, a hidden influence, or something from childhood. Whichever it is, it’s the source of the protagonist’s problem. An unconscious motivation is brought to awareness.

4B) The Devil

The hero must face his own darkness must free himself by gaining knowledge by confronting all that is shadowy, shameful and base in his personality.

4C) The Meaning

This spread of cards continues to focus on Allan’s need to understand his inner self in order to conquer the sorcerer. There are several options. Will he face his own darkness through a dream or a situation the sorcerer has put him in? Will his untrustworthy companions betray him? Will they jeopardize a girl he secretly likes? What is that darkness? Had he done something that he perceives to be as cruel as his father, like pulling the wings off a fly?

5A) The Alternate Future

What could happen, a potential development. This card can also be used to determine aspirations or where trust is placed.

5B) Queen of Cups

Symbolizes the emergence of deep feelings and fantasies which may appear in the character of a woman who is may be either lover or rival. The woman may be mysterious, hypnotic or even seductive.

5C) The Meaning

Allan really likes Becky and she’s done nothing to deserve being held by the sorcerer. Allan finds he can dig down to do what’s right. Or, the sorcerer is a woman and he must overcome her hypnotic ways and again, he can only do that by facing and overcoming his sense of inadequacy.

6A) Future

What lies immediately in the hero’s future. It may be an event, a belief, a fear, a person, an event, an approaching influence, and unresolved factor which must be considered or even something to embrace.

6B) Seven of Pentacles

A difficult work decision must be made – continue with the project or do something new.

6C)The Meaning

Seriously? This card? We already know that Allan has to either overcome his beliefs about himself so he can move forward to be the hero he must be. Come on Allan – embrace your inner self! Actually, this card would fall perfectly in the scheme of the try/fail cycles. It’s the point where he must embrace his inadequacies, move forward and vanquish the sorcerer.

Cards 7-10 (Sword Spread) tell us what lies before our hero.

7A) Mirror

How does the hero see himself? This card reveals his temperament, his way of being or perhaps his self-image, how he presents himself, the idealized version of himself or a talent he can use.

7B) Three of Swords

Strife, conflict or separation, a painful state is necessary as blindness and self-delusion cannot continue.

7C) The Meaning

The Three of Swords says it all. Allan will face strife, conflict and pain because he’s not facing up to the realities of what haunts him and who he really is.

8A) From the Outside

How do others perceive the hero? What are their expectations, their view of the problem, the hero’s effect on them?

8B) The Lovers

Love makes people blind to their choices or actions so one must look carefully at his choices. It may mean making a choice between love and a career. It may mean a love in one’s life.

8C) The Meaning

His need for acceptance, even by the untrustworthy troop with him, makes Allan easily duped and keeps him from facing his fears and sense of inadequacy. This allows the group to take advantage of him for their own benefit and he suffers for that. He may have to choose between Becky (the girl) and the gang (vanquishing the sorcerer).

9A) The Guide or Hopes and Fears

What are the hero’s deepest hopes and fears? This card indicates how the hero will approach obstacles and opportunities.

9B) Ace of Cups

Ready for a journey of love, there is an outpouring of raw, overwhelming feeling. There is a potential for a relationship.

9C) The Meaning

He wants to be loved by his father, anyone. He wants assurance that he is not some horrid warped creature like his father, but a good person at heart.

10A) The Outcome

This card doesn’t mean ‘forever’ but rather tells us what the natural outgrowth from all the things we have divined about the hero. Everything leads to this point.

10B) Six of Swords

Insights smooth difficult times and insight and understanding and dignity and self-respect are maintained.

10C) The Meaning

I didn’t pull this card deliberately! But it is a story worthy conclusion. Insight, understanding and facing his inadequacies smooth the path for Allan who is now able to vanquish the sorcerer, save Becky and maybe even live happily ever after until the next villain appears for who knows what other demons the book holds?

This is a quick example of how Tarot can be used to develop a character. Authors also use Tarot to develop the plot. Mark Teppo’s book explains how he does that so check it out. Here are the two books I used to help divine this blog:

JUMP START YOUR NOVEL by Mark Teppo can be found here.

THE MYTHIC TAROT: A NEW APPROACH TO THE TAROT CARDS can be found here.