There are dozens of books on how to create characters. One that I like is BUILDING BELIEVABLE CHARACTERS by Marc McCutcheon. In it, he will guide you through the process of creating characters that have multiple dimensions–dealing with external traits, personality disorders, the kinds of clothes that they wear, habits and opinions, medical histories, and so on. If you’re a new author, I highly recommend such a book simply because most authors have one or two blind spots in their characterization. For example, when I was young, I wrote my first novel, and my editor called up and asked, “What is your heroine wearing on page 186?” I thought a moment and answered, “Clothes.”

There are dozens of books on how to create characters. One that I like is BUILDING BELIEVABLE CHARACTERS by Marc McCutcheon. In it, he will guide you through the process of creating characters that have multiple dimensions–dealing with external traits, personality disorders, the kinds of clothes that they wear, habits and opinions, medical histories, and so on. If you’re a new author, I highly recommend such a book simply because most authors have one or two blind spots in their characterization. For example, when I was young, I wrote my first novel, and my editor called up and asked, “What is your heroine wearing on page 186?” I thought a moment and answered, “Clothes.”

As a new writer, I didn’t care much about what my characters were wearing. Frankly, as those who have observed my closet first-hand can tell you, I don’t care much about what I am wearing.

I’ve seen new authors who create a cast of characters, and not one of them seems to have a personal relationship. I’ve seen authors who write all characters with the same voice. I once read a story by an author who described the love interest as “the woman with the big tits” for the first five pages. (I quit reading after that, though there a morbid sense of curiosity makes me wonder to this day if she ever got a name, a hair color, or any hint of a personality. Only the absurdity of the author’s approach got me five pages into the story in the first place.)

But I have to admit that all of this cataloguing of traits might be fairly worthless. I can’t see spending eighty pages to create a character’s background for a normal novel. It’s overkill.

An approach that I have found to be far more valuable is one that I haven’t seen in any book. The basic idea is this: stories aren’t about characters so much as they are about growth. In other words, your characters will change and grow throughout a novel, and it isn’t necessarily the character herself that is interesting, but that process of change.

So when I’m generating characters, I often find that I can kick-start a whole story by composing a character who is going to go through a change. Here are a couple of samples:

Sister Mary Teresa had never wanted to make love to a man until she met Father McFarland, and in that instant she repented of her vow of chastity and silently began to plan an affair.

It had only been three days since last I’d seen Sir Fader, yet immediately I knew that something was terribly wrong, for in that time his hair had turned from burnished red to snowy white, and there was a haunted look in his eyes that made me stumble away in fear when he glanced at me.

You can of course think of your own. If you’re writing a story, consider the growth or changes that your character will be required to go through, and then compose a sentence or two describing that moment when your character changes from what he was to what he will be. Eventually, that moment will become a pivotal scene.

For example, in heroic fiction, there is an archetypal moment that occurs when a young man or woman sets aside their fears and decides to risk everything to become a hero. Often, that moment follows the death of a loved one–a father or wife. At the very least, it will usually involve the hero witnessing some terrible injustice.

In the same way, you’ll find that villains need to grow. Many writers make the mistake of trying to create villains who are stagnant. They are bad simply because they are evil. But a far more interesting villain is one who is faced with moral choices, who struggles with them, and does not always do what is evil. He sometimes shows mercy. He sometimes is benevolent. But in the end, when faced with his biggest challenge of all, he falls. In other words, your story should not start with a villain, but should grow a villain.

You’ll find that when you enjoy a story immensely, there is almost always some character growth. One of my favorite movies in recent years was “As Good as it Gets,” with Jack Nicholson. In it, Jack is a horrible man–a smug novelist who is so neurotic that he can hardly step out of his own apartment. He’s both a homophobe and misogynist, and so he is a terribly lonely man. But during the course of the film, he grows tremendously, winning the love of a good woman and finally taking in the gay man next door as a roommate. In the film, each character experiences a life-altering moment that makes them more accepting of others, more loving, and ultimately more human than they had been before.

For each of your characters, you would be wise to look at them and not worry so much about how many nose hairs they have or what their social security number is, but to consider what kind of growth that character might experience in your tales.

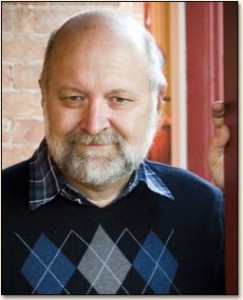

David Farland is an award-winning, New York Times bestselling author who has penned nearly fifty science fiction and fantasy novels for both adults and children. Along the way, he has also worked as the head judge for one of the world’s largest writing contests, as a creative writing instructor, as a videogame designer, as a screenwriter, and as a movie producer. You can find out more about him at his homepage at http://www.davidfarland.net/. Also check out more great advice in his book Million Dollar Outlines. And take some of his online workshops at http://mystorydoctor.com.