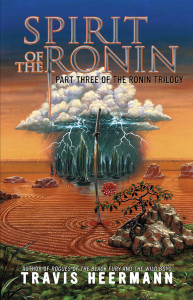

This year, the editor of my Ronin Trilogy gave me an incredible compliment: “In Spirit of the Ronin, every scene does exactly what you intend it to do.” On a day when I was dreadfully worried about whether the newly finished draft of the novel was any good, this came at the perfect time.

I’ll quickly avert my gaze from the implication that apparently I didn’t quite hit that mark every time in previous books. Chalk it up to the learning process.

A lot of know-how about writing scenes is packed into this one sentence, and it comes in levels and/or number of trunk novels.

Level 1 (Chum/Sharkbait, 0 novels): “What’s a scene?”

A scene represents a discrete chunk of a narrative’s time wherein a mix of stuff appears: character interactions, things happening, background information delivery. Changing scenes is useful for switching characters, locations, or time. Shakespeare divided his plays up into acts and scenes, and even numbered his scenes, so I should have scenes, too.

Level 2 (Remora, 1 trunk novel): “I understand that scenes are a dramatically useful way of dividing up a story, but what do you mean you can use them to propel the plot?”

Scenes can propel the plot along if you can end them at compelling moments. Cliffhangers are the most obvious example of this, but not every situation is appropriate for them. Some scenes are more introspective, reactive. Sometimes in a scene, Things Happen. Sometimes, the Character Reacts to Things That Happened.

At this point, think of it this way. To propel the plot forward, end every scene with either a “Yes, but…” or a “No! And moreover…”

To build dramatic tension, the protagonist must be constantly striving and failing against the antagonist, who should always have the upper hand, until the final climactic moment when Everything Hangs in the Balance. You can have the protagonist occasionally succeed at some dramatic moment, but their success should be thwarted or minimized in some way by a worsening of the situation. This represents a “Yes, but …”

Every time the protagonist fails, the antagonist’s advantage is strengthened. Protagonist tries, fails… and then things get even worse. This is the “No, and moreover…”

The reader should leave every scene with a major dramatic question. This question makes them hunger to know what happens next.

Credit goes to Odyssey Writing Workshop’s Jeanne Cavelos for this wisdom.

Level 3 (Tiger Shark, 2 trunk novels): “I understand how to set up scenes with cliffhangers or dramatic questions at the end of each one, but what do you mean scenes have structure?”

The vast majority of stories in the Western storytelling paradigm are structured in three acts. Just like stories, scenes have a Three-Act Structure. Movies, novels, short stories, all have a Three-Act Structure (the nature of this is a whole other topic). For our purposes here, we can break scenes down into mini-acts, each representing the Beginning, Middle, and End of the scene.

Each scene follows one of two patterns.

- Goal (what the character is trying to achieve is established at the beginning of a scene)

- Conflict (the things against which the character struggles in the middle)

- Disaster (the way everything goes to hell at the end of the scene, the cliffhanger)

OR

- Reaction (at the beginning of this scene, character reacts to how things went to hell in the previous scene)

- Dilemma (in the middle of the scene, the character is placed in an even worse situation)

- Decision (at the end of the scene, the character chooses how to move forward)

This pattern is often called Scene and Sequel—a potentially confusing choice of jargon—developed by Dwight Swain in his book Techniques of the Selling Writer. This is not the same kind of scene as Level 1, nor does sequel mean the next movie in a series. Use of Scene & Sequel has become relatively widespread or at least familiar to most professionals.

Level 4 (Hammerhead, 3 trunk novels): “I understand how each scene needs to have a beginning, middle, and end, but do you mean each scene needs a purpose?”

During the revision process—not the composition process—ask the question: What is this scene for? What do I want it to accomplish? I say during the revision process because this is the kind of thinking that is not always helpful when you’re trying to open up your subconscious and let the story bubble out. This is too much thinking, not enough feeling. You may be skilled enough that it happens naturally, un-self-consciously, but if not, this is for the polishing phase.

An effective scene requires it to do at least three things from this list.

- Advance the plot

- Develop character

- Develop the story’s world

- Pique the reader’s interest for the next scene

If you’ve managed the previous levels, #4 is pretty much built in, so you only have to worry about the other three.

And if you can hit all four, every time, that makes you a Literary Effing Great White, and you’ve either passed beyond the Trunk Novel Stage to some serious publication—or you soon will.

Unlocking Levels Beyond

There are doubtless higher skill levels. Becoming a better writer is a lifetime pursuit of excellence. I have not yet unlocked the Mythical Megalodon and Literary Leviathan levels so I don’t know what revelations they contain. I am only vaguely aware of their existence, in the way I was only vaguely aware of the higher realms when I was Level 1 Chum.

One of the hardest parts of writing is not knowing—really not knowing—whether your work is any good. You have to believe it is, even if it might not be—and when you’re shown it isn’t that good, to find a way past this particularly hard knock and keep striving to get better. Keep studying. Keep practicing. Keep learning. It’s all any of us can ever do.

Apparently, unbeknownst to myself, something clicked with Spirit of the Ronin, and my editor saw it. Having someone point it out to you is like ambrosia on the parched soul. There wasn’t anything specific that I learned, or studied. My only explanation is that study and practice came together.

The hardest part is wondering when it will happen again.

About the Author: Travis Heermann

Travis Heermann’s latest novel Spirit of the Ronin, was published in June, 2015.

Travis Heermann’s latest novel Spirit of the Ronin, was published in June, 2015.

Freelance writer, novelist, award-winning screenwriter, editor, poker player, poet, biker, roustabout, he is a graduate of the Odyssey Writing Workshop and the author of Death Wind, The Ronin Trilogy, The Wild Boys, and Rogues of the Black Fury, plus short fiction pieces in anthologies and magazines such as Perihelion SF, Fiction River, Historical Lovecraft, and Cemetery Dance’s Shivers VII. As a freelance writer, he has produced a metric ton of role-playing game work both in print and online, including content for the Firefly Roleplaying Game, Legend of Five Rings, d20 System, and EVE Online.

He lives in New Zealand with a couple of lovely ladies and a burning desire to claim Hobbiton as his own.

You can find him on…