There are few things I like more than unreliable narrators, reluctant heroes, dark protagonists, dogs, and Taco Bell. Some of my favorite characters on television shows, in books, and in comic books are the anti-heroes and villains that have deep, spanning character arcs. I just hate to love Gul Dukat from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, the perpetual heel no matter how hard I root for him to turn into a good guy. Who can say no to The Hound in Game of Thrones? All beefy, reluctant, melty-cheese-face goodness right there. And who isn’t charmed/terrified by Negan in The Walking Dead comics and his filthy, filthy mouth? Kim Coates’ portrayal of Tig on Sons of Anarchy? C’MON, man. The best! And the king of anti-heroes, from which my love of anti-heroes began: Conan the Barbarian.

There are few things I like more than unreliable narrators, reluctant heroes, dark protagonists, dogs, and Taco Bell. Some of my favorite characters on television shows, in books, and in comic books are the anti-heroes and villains that have deep, spanning character arcs. I just hate to love Gul Dukat from Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, the perpetual heel no matter how hard I root for him to turn into a good guy. Who can say no to The Hound in Game of Thrones? All beefy, reluctant, melty-cheese-face goodness right there. And who isn’t charmed/terrified by Negan in The Walking Dead comics and his filthy, filthy mouth? Kim Coates’ portrayal of Tig on Sons of Anarchy? C’MON, man. The best! And the king of anti-heroes, from which my love of anti-heroes began: Conan the Barbarian.

What most of these anti-heroes and villains have in common is this: their behavior is somewhat predictable from early on. Gul Dukat gonna be Gul Dukat, even if he does some good things on occasion. The Hound looks out for himself until paid to do otherwise, with only a few exceptions. Negan tells his enemies exactly what he’s going to do before he does it. He also loves Lucille, and he’s gonna bring her out to play and he’ll talk some poor character’s ear off while doing it. Tig’s always going to be weird on a supreme level, but he has his soft spots. Conan the mercenary, the pirate, the thief, the treasure hunter, the nomad, still lives his life according to a code.

As a good rule of thumb, the reader has to trust a character to do just one thing: act like him/her/themselves.

Gillian Flynn either didn’t get the memo, or doesn’t care about your fragile expectations of her characters. And boy is that ballsy. But if you know anything about her success, it’s turning out pretty well for her.

In the first half of Gillian Flynn’s bestseller Gone Girl, I was amazed. Flynn’s ability to communicate small issues in a marriage, how they can appear and fester just under the surface, was revelatory to me. I sure didn’t pick up Gone Girl expecting such an accurate and subtle commentary on American marriage and the differences between blue-collar and white-collar partner philosophies.

In the first half of Gillian Flynn’s bestseller Gone Girl, I was amazed. Flynn’s ability to communicate small issues in a marriage, how they can appear and fester just under the surface, was revelatory to me. I sure didn’t pick up Gone Girl expecting such an accurate and subtle commentary on American marriage and the differences between blue-collar and white-collar partner philosophies.

But I also didn’t pick up Gone Girl expecting the twist, either. Soft spoiler ahead, so cover your eyes for this and the next paragraph if you plan on reading the book or seeing the movie. As it turns out, BOTH of our narrators, married couple Nick and Amy Dunne, are unreliable to an extreme. Just when we start feeling sorry for Nick, and think he’s getting played by a master, we find that he’s been living a secret life all on his own.

What Gillian Flynn accomplishes in Gone Girl is to take the concept of an unreliable narrator and anti-heroes to another level. When we understand that Nick and Amy can’t be trusted (the first unreliable narrator twist), Flynn twists the narrative knife even further, taking their story to depths most people couldn’t dream up in a million years.

Similarly, in Flynn’s novella The Grownup, the reader is presented with an anti-hero that, at first blush, seems honest and straight forward about who she is: a fake psychic. I’ll not mention her former job so you’re surprised when you read the short story yourself (I’ll just say this: the first two lines of the story are some of the best opening lines I’ve ever read. Talk about a hook! Winky wink). Now, as we, the readers, follow this opportunistic woman, we fall into a haunted house/evil stepson-type scenario. Nothing too surprising here – they are common horror movie tropes. And our protagonist, although a con artist of sorts, still has some admirable attributes, and it’s easy to slip into the story from her perspective. We’re even on her side. (Big spoiler here, so skip to the next paragraph if you want to read this story.) We’re on her side, that is, until we realize too late that she’s not an anti-hero – she’s the villain, and became so under our very noses. And this is Flynn’s trademark. Unreliable narrators to an extreme. Characters that seem like unreliable narrators and anti-heroes who become the villains before the reader can put two and two together.

Similarly, in Flynn’s novella The Grownup, the reader is presented with an anti-hero that, at first blush, seems honest and straight forward about who she is: a fake psychic. I’ll not mention her former job so you’re surprised when you read the short story yourself (I’ll just say this: the first two lines of the story are some of the best opening lines I’ve ever read. Talk about a hook! Winky wink). Now, as we, the readers, follow this opportunistic woman, we fall into a haunted house/evil stepson-type scenario. Nothing too surprising here – they are common horror movie tropes. And our protagonist, although a con artist of sorts, still has some admirable attributes, and it’s easy to slip into the story from her perspective. We’re even on her side. (Big spoiler here, so skip to the next paragraph if you want to read this story.) We’re on her side, that is, until we realize too late that she’s not an anti-hero – she’s the villain, and became so under our very noses. And this is Flynn’s trademark. Unreliable narrators to an extreme. Characters that seem like unreliable narrators and anti-heroes who become the villains before the reader can put two and two together.

As much as I drool over and admire Gillian Flynn’s storytelling, I must admit I don’t come away from her books feeling particularly… good. I feel uncomfortable, ill at ease. I certainly don’t need every book to be a happy ending, but I’m used to anti-hero stories ending in a different way (Conan always accomplishes the quest and gets the girl, after all).

What I take away from Gillian Flynn’s expert storytelling and success is this: do what you do, and do it well. If you’re good at pulling the wool over your readers’ eyes, do it. But always do it well. Flynn creates characters we can empathize with, she can humanize extreme situations, and then she slowly crumbles the foundation of what we thought we knew about those characters and their situation. Flynn uses our very fundamental trust of character (that the character will act like himself/herself/themselves) against us. And it is masterful.

Readers don’t always like to be deceived. In fact, a writer pulling a fast one often makes a reader feel betrayed. But looking at Gone Girl‘s success, it doesn’t appear the readers minded the deception because of how artfully Flynn pulled it off. Don’t be afraid to deceive your reader, but only if you can pull it off, too.

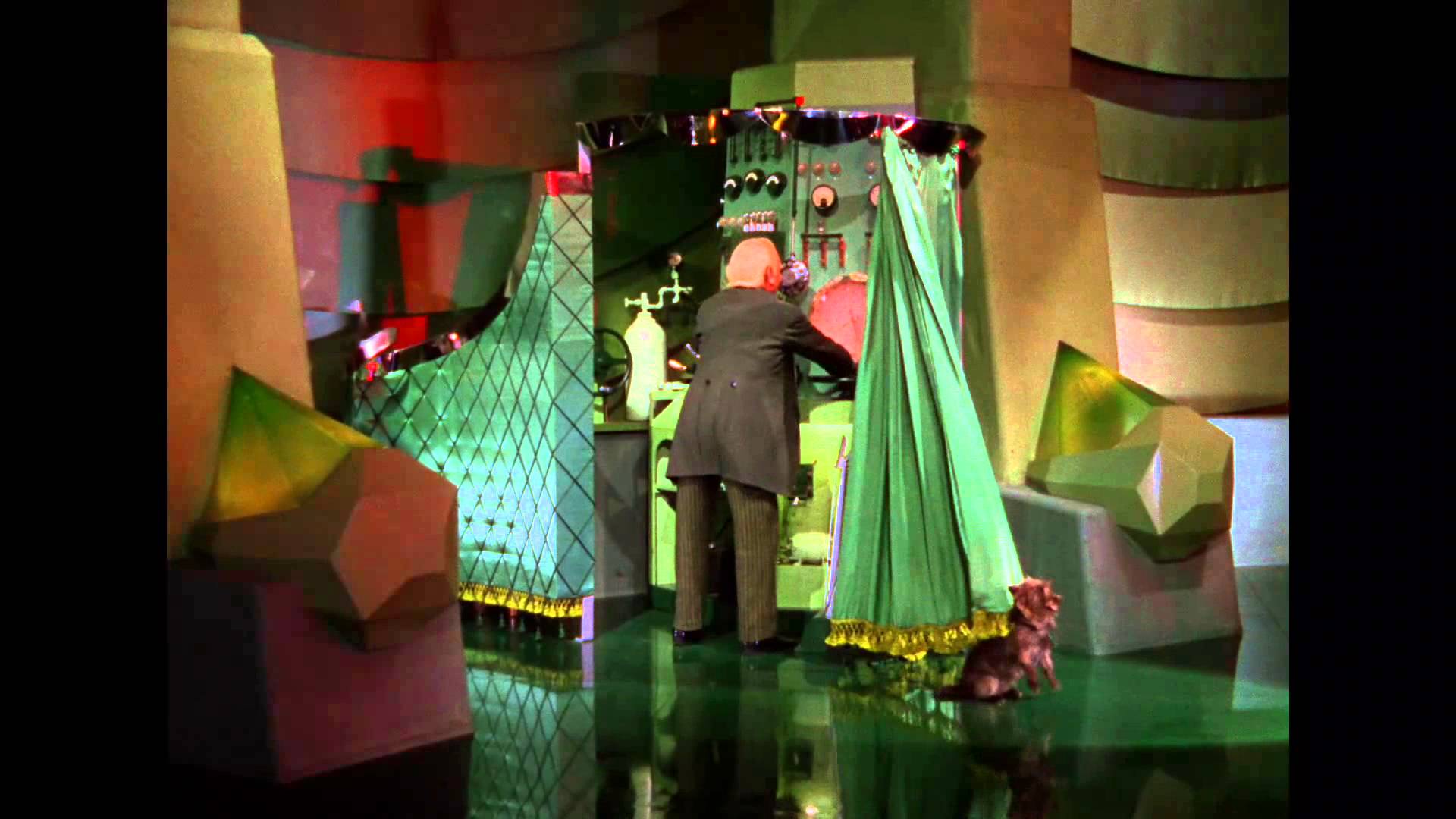

As a child watching The Wizard of Oz, I never suspected a bumbling old man hiding behind a curtain to be the “great and terrible Oz.” I was completely taken aback when Toto pulled back the drapes and revealed the traveling salesman who was pushing all the levers and buttons. I still revel in the concept of a man behind a curtain, but I prefer much darker motives, the pushing of people’s buttons more than any machine, and a more illusory curtain. A good example of this is Brandon Sanderson’s

As a child watching The Wizard of Oz, I never suspected a bumbling old man hiding behind a curtain to be the “great and terrible Oz.” I was completely taken aback when Toto pulled back the drapes and revealed the traveling salesman who was pushing all the levers and buttons. I still revel in the concept of a man behind a curtain, but I prefer much darker motives, the pushing of people’s buttons more than any machine, and a more illusory curtain. A good example of this is Brandon Sanderson’s

For all of you “Agents of Shield” fans, I think you’ll remember that wrench in your gut when you realized, but didn’t want to admit, that Grant Ward was Hydra. Not only was he Hydra, but he was also quite psycho. Everyone’s favorite character started betraying and killing all of his friends. Except for the recently acquired girlfriend, whom he creepily stalked.

For all of you “Agents of Shield” fans, I think you’ll remember that wrench in your gut when you realized, but didn’t want to admit, that Grant Ward was Hydra. Not only was he Hydra, but he was also quite psycho. Everyone’s favorite character started betraying and killing all of his friends. Except for the recently acquired girlfriend, whom he creepily stalked. r not effect his own goals or must further them in some way. He can save his friend’s life, it can seem that it’s because he legitimately cares, and we can find out later that it was only because the backstabber needed information. Besides Grant Ward in Agents of Shield, another great example is in Brandon Sanderson’s Warbreaker. (spoiler alert) Throughout the entire novel, Siri finds in Bluefingers a confidante she can trust, until the very end when he and the Pahn Kahl people turn against her and the kingdom. He was the one person she thought she could trust and with that paradigm shift is a plot twist that changes everything.

r not effect his own goals or must further them in some way. He can save his friend’s life, it can seem that it’s because he legitimately cares, and we can find out later that it was only because the backstabber needed information. Besides Grant Ward in Agents of Shield, another great example is in Brandon Sanderson’s Warbreaker. (spoiler alert) Throughout the entire novel, Siri finds in Bluefingers a confidante she can trust, until the very end when he and the Pahn Kahl people turn against her and the kingdom. He was the one person she thought she could trust and with that paradigm shift is a plot twist that changes everything. ueen in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe? We see his betrayal coming, but his poor siblings have no idea until he’s gone. We can unfold the tragedy with carefully placed clues that the reader puts together piece by piece, gradually discerning the awful news that they hate to admit may be true, like in the famed Narnia series. We can also slam the reader with the betrayal for greater impact, putting them suddenly on the edge of their seats as they wait for the protagonist to find out. Either way works and I think the best choice is whichever one fits with the flavor of your book. Is it wrought with mystery so the betrayal is one of many factors or is it a book of many twists, turns, and tragedies where this can be one more layer on the cake?

ueen in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe? We see his betrayal coming, but his poor siblings have no idea until he’s gone. We can unfold the tragedy with carefully placed clues that the reader puts together piece by piece, gradually discerning the awful news that they hate to admit may be true, like in the famed Narnia series. We can also slam the reader with the betrayal for greater impact, putting them suddenly on the edge of their seats as they wait for the protagonist to find out. Either way works and I think the best choice is whichever one fits with the flavor of your book. Is it wrought with mystery so the betrayal is one of many factors or is it a book of many twists, turns, and tragedies where this can be one more layer on the cake? es for him. Mordo’s negative reaction when he discovers their leader has been using forbidden magic all along is a sign that not all is well. Mordo seems to come around, helping Doctor Strange save the world, and it’s not certain what Mordo will do until the moment comes. Even Mordo doesn’t seem certain what he’ll do. And then he turns his back on his friends and becomes the next super-villain. If we hadn’t already known that Anakin becomes Darth Vader, we might have been on the edge of our seats wondering if he’d really turn to the dark side or come to his senses. Because we do know, it becomes an example for the scenario above. We know it will happen, but how and when is the question. I think the unsure betrayer is one of the most compelling and heart-wrenching scenarios in fiction. It gives our protagonist’s friend a great sense of depth as they struggle with the decision. This one is also hard to pull off well, because we must show those forces of good and evil push and pull in a side character while still keeping the protagonist as the focus. Done well, it’s quite powerful.

es for him. Mordo’s negative reaction when he discovers their leader has been using forbidden magic all along is a sign that not all is well. Mordo seems to come around, helping Doctor Strange save the world, and it’s not certain what Mordo will do until the moment comes. Even Mordo doesn’t seem certain what he’ll do. And then he turns his back on his friends and becomes the next super-villain. If we hadn’t already known that Anakin becomes Darth Vader, we might have been on the edge of our seats wondering if he’d really turn to the dark side or come to his senses. Because we do know, it becomes an example for the scenario above. We know it will happen, but how and when is the question. I think the unsure betrayer is one of the most compelling and heart-wrenching scenarios in fiction. It gives our protagonist’s friend a great sense of depth as they struggle with the decision. This one is also hard to pull off well, because we must show those forces of good and evil push and pull in a side character while still keeping the protagonist as the focus. Done well, it’s quite powerful.