Even with a fantastic opening hook and an explosive inciting incident, many stories spend time slogging through the “muddy middles.” As the name suggests, the middles are the time part way through act two where the story no longer benefits from the momentum of the inciting incident, but also hasn’t reached the point where it is drawn forward by the climax. This sag in tension is a dangerous time for any story as it allows the reader to put the book down. Therefore, deciding how to draw your audience through the middles is an essential part of any plotting.

If you ask a dozen authors how to best navigate the middles, you will often get fourteen answers. In truth, the “best” method depends on what sort of story you are trying to tell and what are the strongest emotional draws for your audience. Rather than listing all the possibilities, I’ll focus my discussion on four techniques that I think can be used in a variety of different stories.

Many thrillers and action/adventure stories will bridge the middles with a series of explosive scenes. By doing so, the author simplifies their task to propelling the reader from scene to scene rather than from initiating event to climax. As the reader progresses through the story, the duration between action sequences should shrink. This gives the illusion of accelerating right up into the climax.

Consider as an example the action/adventure film John Wick. The introduction and inciting incident occur in the first fifteen minutes of the movie and the climax occurs at roughly one hour and fifteen minutes. Taken at a very high level, what happens during the hour between those two points? First, there is a period of milieu and character work to establish the character of John Wick and the rest of the world. Then there is a beating delivered by the big bad and the big bad’s first try/fail cycle to resolve the issue without violence. This is followed by a gun fight, a short period of world exploration, a gun fight, a brief pause for recovery, a fist fight, a briefer pause for a few wise cracks, a gun fight, a yet briefer pause in which John Wick sets some stuff on fire, and once again a gun fight that ends in a capture sequence. John then escapes captivity and dives straight into the climax of the movie. The tension is not allowed to slacken for a moment because John is near constantly either in danger and/or kicking some ass.

Consider as an example the action/adventure film John Wick. The introduction and inciting incident occur in the first fifteen minutes of the movie and the climax occurs at roughly one hour and fifteen minutes. Taken at a very high level, what happens during the hour between those two points? First, there is a period of milieu and character work to establish the character of John Wick and the rest of the world. Then there is a beating delivered by the big bad and the big bad’s first try/fail cycle to resolve the issue without violence. This is followed by a gun fight, a short period of world exploration, a gun fight, a brief pause for recovery, a fist fight, a briefer pause for a few wise cracks, a gun fight, a yet briefer pause in which John Wick sets some stuff on fire, and once again a gun fight that ends in a capture sequence. John then escapes captivity and dives straight into the climax of the movie. The tension is not allowed to slacken for a moment because John is near constantly either in danger and/or kicking some ass.

Though the thriller model is effective, it won’t work universally. After all, mystery audiences won’t be satisfied by explosions and flying fists. Instead, they are looking for intellectual stimulation. However, it isn’t enough to simply give them a puzzle. As the story continues, they need to feel as if they are coming closer to the solution. The key here is to ensure that each new answer they find along the way complicates the puzzle by being either incomplete, misleading, or raising yet more questions. The best, recent example I can think of to illustrate this style of plotting is the movie Arrival. Don’t worry about spoilers. Unlike John Wick (2014), Arrival (2016) is still new enough that I will only speak in broad strokes.

I believe that the story of Arrival works as well as it does because everyone goes into a first contact story expecting an overt conflict between humanity and the aliens. However, twists this trope on its head, which is intriguing in and of itself. The main story is a mystery driven by the question, “What do the aliens want?” Along the way, we the audience are given pieces of the puzzle in such a way that they don’t all come together until the very end. This plotting structure latches onto our fundamental human curiosity and pulls us forward with the illusion of progress towards getting an ultimate answer.

I believe that the story of Arrival works as well as it does because everyone goes into a first contact story expecting an overt conflict between humanity and the aliens. However, twists this trope on its head, which is intriguing in and of itself. The main story is a mystery driven by the question, “What do the aliens want?” Along the way, we the audience are given pieces of the puzzle in such a way that they don’t all come together until the very end. This plotting structure latches onto our fundamental human curiosity and pulls us forward with the illusion of progress towards getting an ultimate answer.

Where action/adventure plots seek to satisfy a sense of physicality and mysteries work to stimulate intellectual curiosity, romances play on the human need for connection. Will our point of view character be able to woo their paramour? Can our protagonist choose between two appealing, yet opposing romantic interests? How will our two (or more) romantic leads be able to overcome whatever forces hold them apart and end the story together? No matter the details, the drive is still the same. Will our protagonist(s) be able to achieve their need for connection? As such, we writers need to maintain tension by repeatedly denying our characters, and by proxy the readers, the connection they desire. We can do this in two major ways.

First is by introducing conflict internal to the relationship. By giving the romantic interests compelling personal conflicts and reservations, you allow them to stand in the way of their own happiness. It’s important to note that the reasons holding your characters apart need to be fundamental to their character, something substantial enough that it can withstand several try/fail cycles and significant enough that it poses a legitimate threat to the relationship. An example of this technique can be found in the early relationship between Eve Dallas and Roarke in Naked in Death by JD Robb. During her investigation of a sensitive homicide, Lieutenant Dallas meets Roarke and sparks fly. She feels conflicted because she can’t eliminate him as a suspect in her case, but also increasingly can’t deny her developing feelings for him. Her gut tells her that Roarke is innocent, but she can’t prove it. Robb draws us through the romantic arc by having Dallas’ blooming feelings clash with her sense of duty.

First is by introducing conflict internal to the relationship. By giving the romantic interests compelling personal conflicts and reservations, you allow them to stand in the way of their own happiness. It’s important to note that the reasons holding your characters apart need to be fundamental to their character, something substantial enough that it can withstand several try/fail cycles and significant enough that it poses a legitimate threat to the relationship. An example of this technique can be found in the early relationship between Eve Dallas and Roarke in Naked in Death by JD Robb. During her investigation of a sensitive homicide, Lieutenant Dallas meets Roarke and sparks fly. She feels conflicted because she can’t eliminate him as a suspect in her case, but also increasingly can’t deny her developing feelings for him. Her gut tells her that Roarke is innocent, but she can’t prove it. Robb draws us through the romantic arc by having Dallas’ blooming feelings clash with her sense of duty.

The second option is to introduce some element of external conflict, where your romantic interests strive together to try to overcome a barrier from outside the relationship. Again whatever the threat is, it needs to be big enough to possibly end the relationship. Twenty three books later in Innocent in Death, Robb introduces one of Roarke’s old girlfriends into the storyline to give Eve an extra emotional complication on top of her homicide investigation. The ex-girlfriend’s presence causes friction between Eve and Roarke and in so doing threatens their, by then well established, relationship. In both cases, the emotional distance between the characters drives our readers forward; they want to make sure that Eve and Roarke end up together.

The second option is to introduce some element of external conflict, where your romantic interests strive together to try to overcome a barrier from outside the relationship. Again whatever the threat is, it needs to be big enough to possibly end the relationship. Twenty three books later in Innocent in Death, Robb introduces one of Roarke’s old girlfriends into the storyline to give Eve an extra emotional complication on top of her homicide investigation. The ex-girlfriend’s presence causes friction between Eve and Roarke and in so doing threatens their, by then well established, relationship. In both cases, the emotional distance between the characters drives our readers forward; they want to make sure that Eve and Roarke end up together.

It is important to note that though all the techniques I have described are different, they all appeal to the readers’ emotional draws. Ultimately, we need to ensure that our readers are always having fun, even when the momentum slows. Lucky for us, writers start their careers as fans of their genre. We know what fun is for the genre and our own enjoyment can serve as a metric for how well we are achieving that goal. Granted, this doesn’t hold true for the twenty seventh edit where you brains are leaking out of your ears. Rather, how much fun are you having in the moment of drafting? How much do you enjoy reading your story after letting it rest for a time? If you as the writer aren’t having fun, chances are that your readers will feel much the same way.

So if you ever find yourself drafting your manuscript and just slogging through a slow section, take a moment to step back and reevaluate. Why aren’t you having fun? Is there something about this scene you can change to make it more appealing? Does this scene really need to be here or in the book at all? You don’t always have the luxury of changing or dropping a scene. Sometimes you just need to power through it and fix the problem in editing. However, writing should be a joy. If you aren’t having a good time, it’s okay to take a step back and find ways to make your story more awesome.

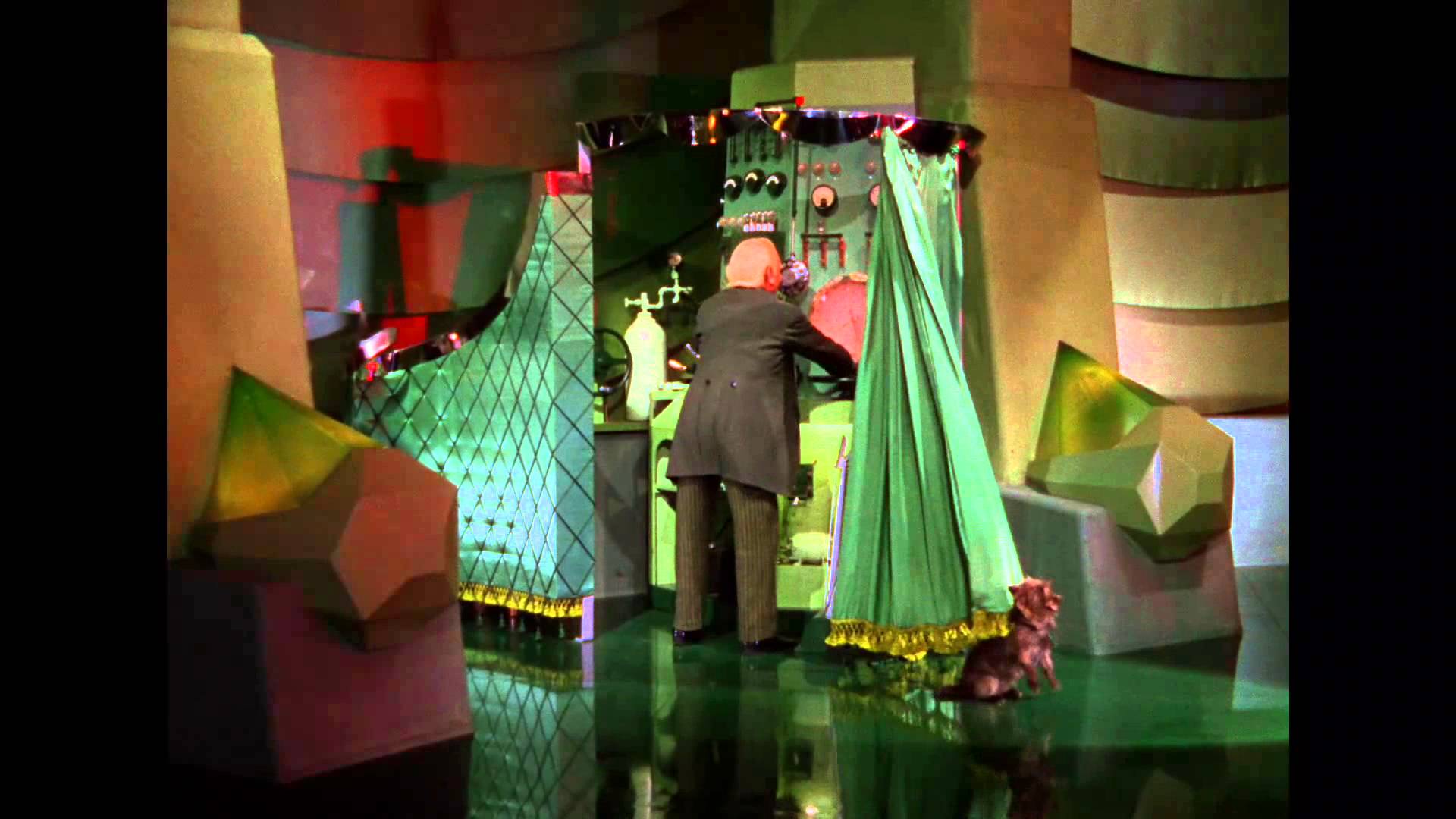

As a child watching The Wizard of Oz, I never suspected a bumbling old man hiding behind a curtain to be the “great and terrible Oz.” I was completely taken aback when Toto pulled back the drapes and revealed the traveling salesman who was pushing all the levers and buttons. I still revel in the concept of a man behind a curtain, but I prefer much darker motives, the pushing of people’s buttons more than any machine, and a more illusory curtain. A good example of this is Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn trilogy.

As a child watching The Wizard of Oz, I never suspected a bumbling old man hiding behind a curtain to be the “great and terrible Oz.” I was completely taken aback when Toto pulled back the drapes and revealed the traveling salesman who was pushing all the levers and buttons. I still revel in the concept of a man behind a curtain, but I prefer much darker motives, the pushing of people’s buttons more than any machine, and a more illusory curtain. A good example of this is Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn trilogy. Colette Black lives in the far outskirts of Phoenix, Arizona with her family, 2 dogs, a mischievous cat and the occasional unwanted scorpion. Author of the Mankind’s Redemption Series, The Number Prophecy series, and the upcoming Legends of Power series, Colette writes New Adult and Young Adult sci-fi and fantasy novels with kick-butt characters, lots of action, and always a touch of romance. Find her at www.coletteblack.net

Colette Black lives in the far outskirts of Phoenix, Arizona with her family, 2 dogs, a mischievous cat and the occasional unwanted scorpion. Author of the Mankind’s Redemption Series, The Number Prophecy series, and the upcoming Legends of Power series, Colette writes New Adult and Young Adult sci-fi and fantasy novels with kick-butt characters, lots of action, and always a touch of romance. Find her at www.coletteblack.net

For all of you “Agents of Shield” fans, I think you’ll remember that wrench in your gut when you realized, but didn’t want to admit, that Grant Ward was Hydra. Not only was he Hydra, but he was also quite psycho. Everyone’s favorite character started betraying and killing all of his friends. Except for the recently acquired girlfriend, whom he creepily stalked.

For all of you “Agents of Shield” fans, I think you’ll remember that wrench in your gut when you realized, but didn’t want to admit, that Grant Ward was Hydra. Not only was he Hydra, but he was also quite psycho. Everyone’s favorite character started betraying and killing all of his friends. Except for the recently acquired girlfriend, whom he creepily stalked. r not effect his own goals or must further them in some way. He can save his friend’s life, it can seem that it’s because he legitimately cares, and we can find out later that it was only because the backstabber needed information. Besides Grant Ward in Agents of Shield, another great example is in Brandon Sanderson’s Warbreaker. (spoiler alert) Throughout the entire novel, Siri finds in Bluefingers a confidante she can trust, until the very end when he and the Pahn Kahl people turn against her and the kingdom. He was the one person she thought she could trust and with that paradigm shift is a plot twist that changes everything.

r not effect his own goals or must further them in some way. He can save his friend’s life, it can seem that it’s because he legitimately cares, and we can find out later that it was only because the backstabber needed information. Besides Grant Ward in Agents of Shield, another great example is in Brandon Sanderson’s Warbreaker. (spoiler alert) Throughout the entire novel, Siri finds in Bluefingers a confidante she can trust, until the very end when he and the Pahn Kahl people turn against her and the kingdom. He was the one person she thought she could trust and with that paradigm shift is a plot twist that changes everything. ueen in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe? We see his betrayal coming, but his poor siblings have no idea until he’s gone. We can unfold the tragedy with carefully placed clues that the reader puts together piece by piece, gradually discerning the awful news that they hate to admit may be true, like in the famed Narnia series. We can also slam the reader with the betrayal for greater impact, putting them suddenly on the edge of their seats as they wait for the protagonist to find out. Either way works and I think the best choice is whichever one fits with the flavor of your book. Is it wrought with mystery so the betrayal is one of many factors or is it a book of many twists, turns, and tragedies where this can be one more layer on the cake?

ueen in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe? We see his betrayal coming, but his poor siblings have no idea until he’s gone. We can unfold the tragedy with carefully placed clues that the reader puts together piece by piece, gradually discerning the awful news that they hate to admit may be true, like in the famed Narnia series. We can also slam the reader with the betrayal for greater impact, putting them suddenly on the edge of their seats as they wait for the protagonist to find out. Either way works and I think the best choice is whichever one fits with the flavor of your book. Is it wrought with mystery so the betrayal is one of many factors or is it a book of many twists, turns, and tragedies where this can be one more layer on the cake? es for him. Mordo’s negative reaction when he discovers their leader has been using forbidden magic all along is a sign that not all is well. Mordo seems to come around, helping Doctor Strange save the world, and it’s not certain what Mordo will do until the moment comes. Even Mordo doesn’t seem certain what he’ll do. And then he turns his back on his friends and becomes the next super-villain. If we hadn’t already known that Anakin becomes Darth Vader, we might have been on the edge of our seats wondering if he’d really turn to the dark side or come to his senses. Because we do know, it becomes an example for the scenario above. We know it will happen, but how and when is the question. I think the unsure betrayer is one of the most compelling and heart-wrenching scenarios in fiction. It gives our protagonist’s friend a great sense of depth as they struggle with the decision. This one is also hard to pull off well, because we must show those forces of good and evil push and pull in a side character while still keeping the protagonist as the focus. Done well, it’s quite powerful.

es for him. Mordo’s negative reaction when he discovers their leader has been using forbidden magic all along is a sign that not all is well. Mordo seems to come around, helping Doctor Strange save the world, and it’s not certain what Mordo will do until the moment comes. Even Mordo doesn’t seem certain what he’ll do. And then he turns his back on his friends and becomes the next super-villain. If we hadn’t already known that Anakin becomes Darth Vader, we might have been on the edge of our seats wondering if he’d really turn to the dark side or come to his senses. Because we do know, it becomes an example for the scenario above. We know it will happen, but how and when is the question. I think the unsure betrayer is one of the most compelling and heart-wrenching scenarios in fiction. It gives our protagonist’s friend a great sense of depth as they struggle with the decision. This one is also hard to pull off well, because we must show those forces of good and evil push and pull in a side character while still keeping the protagonist as the focus. Done well, it’s quite powerful. Consider as an example the action/adventure film John Wick. The introduction and inciting incident occur in the first fifteen minutes of the movie and the climax occurs at roughly one hour and fifteen minutes. Taken at a very high level, what happens during the hour between those two points? First, there is a period of milieu and character work to establish the character of John Wick and the rest of the world. Then there is a beating delivered by the big bad and the big bad’s first try/fail cycle to resolve the issue without violence. This is followed by a gun fight, a short period of world exploration, a gun fight, a brief pause for recovery, a fist fight, a briefer pause for a few wise cracks, a gun fight, a yet briefer pause in which John Wick sets some stuff on fire, and once again a gun fight that ends in a capture sequence. John then escapes captivity and dives straight into the climax of the movie. The tension is not allowed to slacken for a moment because John is near constantly either in danger and/or kicking some ass.

Consider as an example the action/adventure film John Wick. The introduction and inciting incident occur in the first fifteen minutes of the movie and the climax occurs at roughly one hour and fifteen minutes. Taken at a very high level, what happens during the hour between those two points? First, there is a period of milieu and character work to establish the character of John Wick and the rest of the world. Then there is a beating delivered by the big bad and the big bad’s first try/fail cycle to resolve the issue without violence. This is followed by a gun fight, a short period of world exploration, a gun fight, a brief pause for recovery, a fist fight, a briefer pause for a few wise cracks, a gun fight, a yet briefer pause in which John Wick sets some stuff on fire, and once again a gun fight that ends in a capture sequence. John then escapes captivity and dives straight into the climax of the movie. The tension is not allowed to slacken for a moment because John is near constantly either in danger and/or kicking some ass. I believe that the story of Arrival works as well as it does because everyone goes into a first contact story expecting an overt conflict between humanity and the aliens. However, twists this trope on its head, which is intriguing in and of itself. The main story is a mystery driven by the question, “What do the aliens want?” Along the way, we the audience are given pieces of the puzzle in such a way that they don’t all come together until the very end. This plotting structure latches onto our fundamental human curiosity and pulls us forward with the illusion of progress towards getting an ultimate answer.

I believe that the story of Arrival works as well as it does because everyone goes into a first contact story expecting an overt conflict between humanity and the aliens. However, twists this trope on its head, which is intriguing in and of itself. The main story is a mystery driven by the question, “What do the aliens want?” Along the way, we the audience are given pieces of the puzzle in such a way that they don’t all come together until the very end. This plotting structure latches onto our fundamental human curiosity and pulls us forward with the illusion of progress towards getting an ultimate answer. First is by introducing conflict internal to the relationship. By giving the romantic interests compelling personal conflicts and reservations, you allow them to stand in the way of their own happiness. It’s important to note that the reasons holding your characters apart need to be fundamental to their character, something substantial enough that it can withstand several try/fail cycles and significant enough that it poses a legitimate threat to the relationship. An example of this technique can be found in the early relationship between Eve Dallas and Roarke in Naked in Death by JD Robb. During her investigation of a sensitive homicide, Lieutenant Dallas meets Roarke and sparks fly. She feels conflicted because she can’t eliminate him as a suspect in her case, but also increasingly can’t deny her developing feelings for him. Her gut tells her that Roarke is innocent, but she can’t prove it. Robb draws us through the romantic arc by having Dallas’ blooming feelings clash with her sense of duty.

First is by introducing conflict internal to the relationship. By giving the romantic interests compelling personal conflicts and reservations, you allow them to stand in the way of their own happiness. It’s important to note that the reasons holding your characters apart need to be fundamental to their character, something substantial enough that it can withstand several try/fail cycles and significant enough that it poses a legitimate threat to the relationship. An example of this technique can be found in the early relationship between Eve Dallas and Roarke in Naked in Death by JD Robb. During her investigation of a sensitive homicide, Lieutenant Dallas meets Roarke and sparks fly. She feels conflicted because she can’t eliminate him as a suspect in her case, but also increasingly can’t deny her developing feelings for him. Her gut tells her that Roarke is innocent, but she can’t prove it. Robb draws us through the romantic arc by having Dallas’ blooming feelings clash with her sense of duty. The second option is to introduce some element of external conflict, where your romantic interests strive together to try to overcome a barrier from outside the relationship. Again whatever the threat is, it needs to be big enough to possibly end the relationship. Twenty three books later in Innocent in Death, Robb introduces one of Roarke’s old girlfriends into the storyline to give Eve an extra emotional complication on top of her homicide investigation. The ex-girlfriend’s presence causes friction between Eve and Roarke and in so doing threatens their, by then well established, relationship. In both cases, the emotional distance between the characters drives our readers forward; they want to make sure that Eve and Roarke end up together.

The second option is to introduce some element of external conflict, where your romantic interests strive together to try to overcome a barrier from outside the relationship. Again whatever the threat is, it needs to be big enough to possibly end the relationship. Twenty three books later in Innocent in Death, Robb introduces one of Roarke’s old girlfriends into the storyline to give Eve an extra emotional complication on top of her homicide investigation. The ex-girlfriend’s presence causes friction between Eve and Roarke and in so doing threatens their, by then well established, relationship. In both cases, the emotional distance between the characters drives our readers forward; they want to make sure that Eve and Roarke end up together.