Like many of you, I read a lot. I love the new stuff and the classics. LOTR, Les Miserables, Moby Dick, all fantastic books. But there is no denying that they hold a different voice than novels of today. It’s not just words either.

First Person POV like, “Call me Ishmael. Some years ago- never mind how long precisely- having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought…” has changed. Before it was like the telling of something that happened. But now, even though most First Person POVs are written in past tense, there is a closeness to them that makes it feel as if it is happening now. Present tense often has the effect of feeling like it is taking place in the near future.

First Person today or Close Third allow the reader to get inside the POV character’s head. This sets the medium apart from movies or television and I would propose that this is why the book is most often better than the movie.

For an author to do this effectively, the character needs to be alive with real thoughts and preferences and opinions. How else will they react to what comes their way? And isn’t this fantastic story telling? When the characters take hold and even argue with us the author.

I saw a documentary about the filming of Indiana Jones, Raiders of the Lost Ark. There is a scene where a samurai guy whips around his sword and taunts Jones. The documentary said that the original script called for an intricate fight scene where Jones eventually beats the Samurai. But Harrison Ford argued that his character had a gun and would simply shoot the Samurai dead. The story was rewritten.

Recently I have been writing a thriller involving a hitman, an FBI agent, a financial guru in witness protection, and I needed another character to round out the mix—a face of the evil corporate conglomerate. Fei. She is a middle-aged Chinese national and she runs a section of the corporation, laundering money made from sex trafficking and drugs.

I’m a discovery writer so often times I start with an idea and see where it goes with a distant idea in mind. I did not expect what Fei decided to do.

I needed her to ask the hitman to kill this guy, but Fei let me know that this was not an easy thing for her to do and that she’d developed feelings for this dude. I pushed it. She had her lover killed. Part of her was sad, and another felt power and control. She handled the death in a very interesting way. Two chapters later and Fei is now a serial killer. I did not expect that at all, but Fei, with her personality, her childhood issues, her lust and disgust for men, her struggling marriage with a husband who is reluctant to come out of the closet, all of these dynamics have formed and created Fei, a person, a character, someone that I would recognize if I bumped into her on the street (and then I’d run like hell in the opposite direction).

Real characters aren’t cliché. They aren’t faceless drones. They are a compilation of many people. They have wants and goals and dreams and they struggle and have weaknesses. And when they are real, we as readers recognize that and the story resonates with us.

I watch people. (Not in a creepy way). I observe their mannerisms. I listen to their word choices. I notice their posture and eye movements. These things make someone unique. And I ask them questions. I listen to how they respond. I strive to understand their ambitions and fears.

All of these mesh and mingle and come out in my writing.

I came up with Jared Sanderson about 7 years ago. He is very real to me. I could describe his physical features that are a mesh of three of my friends. But this little segment, which is his intro into the story, shows a bit of who he is as a character.

“Jared Sanderson gnawed on the side of his thumb as he waited for the attorney. He had forgotten to moisturize so his skin flaked and cracked at the sides of his fingers. By impulse, he chewed away the dead skin, especially when nervous.”

THE UNKNOWN SOLDIER

I live in Arizona with my family, wife and five kids and a little dog. I write fiction, thrillers and soft sci-fi with a little short horror on the side. I hold an MBA and work in finance for a biotechnology firm.

I volunteer with the Boy Scouts, play and write music, and enjoy everything outdoors. I’m also a novice photographer.

You can check out my books here or at my website www.jacekillan.com.

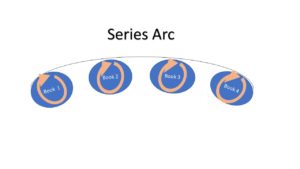

I speak to beginning writers all the time about crafting series. And, after leading off with the whole complete story deal above, I break out the Inception-esque logic of a book-within a book-within a book. Because, really, that’s what we’re writing. The story arc is our overall plot and each book can be seen as an act within the epic structure.

I speak to beginning writers all the time about crafting series. And, after leading off with the whole complete story deal above, I break out the Inception-esque logic of a book-within a book-within a book. Because, really, that’s what we’re writing. The story arc is our overall plot and each book can be seen as an act within the epic structure.