A guest post by VICTORIA MORRIS.

There’s an oblong granite stone just behind a wrought iron fence. You can’t see it clearly unless you walk around the gate. Continue through the hallowed ground until you’re standing just to the left of the gatehouse, under the shade of a hundred year-old weeping willow lending relief from the day.

There are three names on that headstone. The first two, on either end, aren’t similar in any way. The numbers beneath the names are as different as the names themselves. But what is carved between them, binds them all together.

We’ve all seen grave stones. They bear cherished titles: Beloved wife, sister, mother, grandmother. Written just below the name are years. In this case, 1927 ~ 2007.

Have you ever pondered what is really being said in that short last phrase? It isn’t the day of birth and the day of death that tell the story. It’s the dash between them.

Hidden inside that one mark, is a lifetime. All the choices and the entire world of that person. Every joy and every sorrow. Every minute of every day that became the pages of her life.

Changes happened. She grew up during the great depression. She helped work on a farm, and she made sure that she, her little brother, and sister all made it to school. Then she married at fifteen. And promptly sent her brand new husband off to fight in World War 2.

More changes came. He almost didn’t come home when a bullet found his chest, and death swarmed all around him. If a member of his troop hadn’t seen him just barely pointing to his own pocket, to where the rain slicker each of them kept was held, they would have left him in their retreat. Instead, they would use that thin plastic to carry him off the still engaged battlefield. Had they not, children never would have been born.

But he did come home. And their choices together added more pages to their story.

They tried and failed at a few things. But they didn’t give up. They kept on moving, together.

They changed their scenery, moving from the farm into a little white house on an island, where they raised their family of ten children.

The story of the life goes on, adding more chapters. Many more years. Many more joys and happy days. Along with ones that brought tears. All of this, happening during that dash chiseled in a few skillful taps into a white-gray granite.

We all face trials, joys, choices, successes, and failures in life. It’s how we choose to view them, that determines how we classify them and how we embrace, rather than resist them, that helps to make our life great.

Sometimes, it’s within the trials and errors that we find the paths to the greatest joys. Who among the writers here, hasn’t found inspiration by changing the scenery. Inspired images come raining down in the shower, that moments before were no where near existing. And you have to rush to dry off to get them all onto paper. Found the answer to a perplexing scene where you least expected. Located the keys in the last place you looked.

Great inventions nearly always happen that way. Penicillin, capable of saving and helping a life, first existed as mold on a piece of bread. But someone looked at that moldy bread differently, and saw the flash of an idea.

Plot twists change the way we see things. One thousand ways to not make a light bulb happened, before the light bulb did.

Losing something worth everything can be the hardest place to start again. But if you have the courage to begin again, perhaps some of your greatest yet-to-bes, are waiting for you there.

Changes kept happening for that couple. He passed away the day after their 49th anniversary. Cancer finally taking him, after the bullet that stayed in his lung the rest of his life couldn’t.

She mourned him. But before too long, another man crossed her path. Having dealt with his own dash, life had been hard. He didn’t smile much. He spoke with a very soft voice, if at all. But she showed him how to smile. And in showing him, found a joy she’d never experienced before, even in a life-long love.

Then cancer came again. And twice, she had to bury that love.

We all face things that seem insurmountable. Troubles, illness, job losses, moves to places unknown. Things that will shape our stories. But we have the power to choose how that new shape looks. We have the opportunity to turn the unknown into the greatest thing that will ever happen, just by deciding to see it that way in the beginning.

She mourned a second time. This time in a completely different way. She was so sad that she had to choose where to go, whom to lie beside when her time came. Until she realized, she didn’t have to choose between them. She felt she needed to share it with her family, but not a single one of them objected to her idea.

She moved her first husband to lie at her left. Her second would be buried to her right. Leaving the space between them for herself. Connected to them both in death, the loves of her life.

She spent her last years happy. Even though the pain of losing each of them was always with her, the joy that each had given surrounded her completely. There nearly wasn’t a day on her wipe board calendar that did not celebrate a birthday of someone close.

Then the day came when she was laid to rest between her two loves, and her dash was chiseled. Though there were many many tears, there was even more laughter. Because if there was one consistent thing about her, my grandmother knew how to laugh.

A different outcome on that Okinawa battlefield would have caused an enormous difference in my life. I’m very thankful for those men that stopped and looked, so very far away and long ago. Without their bravery in the face of an ongoing destructive force, my mother would have never been born. Without her, me. A scary choice faced them when they stopped for one wounded soldier, not unlike some of choices we ourselves face today.

That headstone is complete now. It stands as a quiet memorial of three lives that influenced my own deeply. My grandfather was an artist and a poet, my grandmother the first to show me what music could do for the soul. My second grandpa, who came and left too quickly for me to get to love deep enough, but to whom I am forever grateful for giving grandma so much joy. There, behind that wrought iron fence, shaded by that willow. Even though I don’t get to visit it very often, the symbol of those words and dashes and the stories they hold are always with me.

Every story deserves its chance to be told. Don’t be afraid to share the failures along with the successes. Don’t steer clear of the hard choices you may face, if you can imagine a different way of seeing through them.

Each choice, every chance, is one more way to learn if the vision of your life can work. And even if it’s not how you pictured it the first time, you may find something you never knew was there. And that something might very well change your dash forever.

Victoria Morris Bio: Victoria lives on the edge of a mysty magical forest in the Pacific Northwest with one husband, two daughters, a big white dog and one huge resident bald eagle that likes to circle over her house when she brings in the groceries. A lifelong artist and not quite as long writer, Victoria is building a universe inside her head that has taken form in a six book fantasy series, with a middle grade trilogy on the side. While illustrating the world and all its characters is always on her mind, she draws portraits in her spare time to relax. Find out more here.

Victoria Morris Bio: Victoria lives on the edge of a mysty magical forest in the Pacific Northwest with one husband, two daughters, a big white dog and one huge resident bald eagle that likes to circle over her house when she brings in the groceries. A lifelong artist and not quite as long writer, Victoria is building a universe inside her head that has taken form in a six book fantasy series, with a middle grade trilogy on the side. While illustrating the world and all its characters is always on her mind, she draws portraits in her spare time to relax. Find out more here.

There are many parts of creating a new novel, and creating realistic characters is probably one of the most challenging ones. Characters need to be believable. They need to have their own personality, habits, and traits that set them apart from others. If done correctly, the reader will be able to relate. They’ll understand and feel concerned. It’ll pull them deeper into the novel and they’ll keep reading to figure out what will happen. If done poorly, it will throw them out of the novel. They won’t be able to believe and before long, they’ll look elsewhere and leave your novel behind.

There are many parts of creating a new novel, and creating realistic characters is probably one of the most challenging ones. Characters need to be believable. They need to have their own personality, habits, and traits that set them apart from others. If done correctly, the reader will be able to relate. They’ll understand and feel concerned. It’ll pull them deeper into the novel and they’ll keep reading to figure out what will happen. If done poorly, it will throw them out of the novel. They won’t be able to believe and before long, they’ll look elsewhere and leave your novel behind.

Room. He has never been outside. He hasn’t received any sort of education, apart from the one his mother tries to give him, which makes his sentence construction short and plain. He only describes what he sees, not knowing exactly what certain things mean. But you, the reader, know exactly what it means. And it makes your stomach churn and your heart ache.

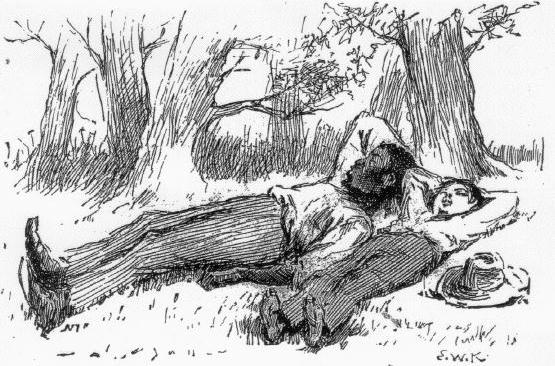

Room. He has never been outside. He hasn’t received any sort of education, apart from the one his mother tries to give him, which makes his sentence construction short and plain. He only describes what he sees, not knowing exactly what certain things mean. But you, the reader, know exactly what it means. And it makes your stomach churn and your heart ache. causing havoc. What Twain did so brilliantly was deciding to tell the story from Huck’s perspective, showing us the charm and charisma Huck has to offer, so we can’t help but love the little shit. Using stylistic voicing, Twain made us relate to an otherwise potentially annoying character.

causing havoc. What Twain did so brilliantly was deciding to tell the story from Huck’s perspective, showing us the charm and charisma Huck has to offer, so we can’t help but love the little shit. Using stylistic voicing, Twain made us relate to an otherwise potentially annoying character.