The music was a dirge, some long-forgotten Celtic lament full of wailing. It washed over me like surf over a half-buried corpse at low tide. Ira stood behind the bar cleaning the same glass he’d been running a dirty towel over for the past ten years.

The music was a dirge, some long-forgotten Celtic lament full of wailing. It washed over me like surf over a half-buried corpse at low tide. Ira stood behind the bar cleaning the same glass he’d been running a dirty towel over for the past ten years.

I raised an eyebrow in his direction, just a flicker. It was all I needed. A beer slid down the bar at me. I smiled. We’d been doing this a long time.

I didn’t turn when I heard the door open. Didn’t have to. When Ira’s hand froze on the glass, I knew there was something worth looking at. I peeked at the mirror behind him. The thing in the doorway definitely wasn’t from around here. Neither was whatever it had on a leash, a beast of roughly the same species, but down on all fours.

Both of their heads turned in unison, the noonday sun casting a halo around, squat, inhuman forms. Their bloodshot eyes locked on me, and on they came. I lost an angle on them in the mirror, but the thump of bare, leathery feet and hands placed them right behind me. I took a sip of beer and stared straight ahead.

Your move, I thought as the stench of sulfur wafted around me. Seconds ticked by. A strong hand clamped down on my shoulder, turned me on the barstool, slow enough not to spill the beer still in my hand. That was polite, I thought.

It was the one on all fours that had the intelligent eyes. Strange, that.

“Hoar’thuft. Moid dan sul bree ik rael Jonny Stiles?” it croaked in a voice that was equal parts whisper and bandsaw.

I stared at the little one for exactly three seconds. “Yeah? Who’s asking?” My eyes shifted to the one standing. It smiled, or, at least did what demons use for a smile… all teeth and wide eyes, the sort of look that wakes old church ladies up with screams and sweaty sheets.

“Wuldrix cu sein Beelzebub,” the short one growled.

It was an order, not a request.

My eyes never left his… or its… I could never tell with demons.

“Ira,” I said slowly, “hold my spot. I’ll be back in an hour.”

It was the little one’s turn to smile.

* * *

Colette started April off with a prompt about aliens and bars, the intention being a discussion of voice and perspective in fiction. It sounded like a writing prompt to me, so I came up with what you just read.

(NOTE: Don’t be surprised if you see that in a short story from me one of these days.)

What’s germane to this month’s Fictorian topic is what we can deduce from just 380 words:

- This is going to be a first-person POV story

- We’ll pretty much only know what the protagonist Jonny Stiles knows

- The tone and word choices throughout let us know this is noir fiction and probably detective noir

- “Alien” doesn’t have to mean from another country or planet

- Jonny Stiles is a regular in Ira’s bar and might have a drinking problem

- Jonny isn’t surprised by the presence of demons

- Jonny speaks the language of Hell

- Demons know him by name

- Jonny isn’t surprised to hear that the Devil wants to see him

- Jonny is cool as a cucumber at the thought of going to Hell

I like to think this is the sort of prose that sucks a reader in and prompts the following questions:

- Who is Jonny Stiles?

- Why is he so calm about meeting the Devil in Hell?

- Why the hell does the Devil want to see Jonny?

It’s these kinds of questions that prompt a reader to care about a protagonist, and, more importantly, encourage the reader to keep going. Furthermore, the advantage of first-person is that the reader knows—or at least hopes—that they’ll be visiting Hell as “I” not as someone else. The reader has a vested interest in the outcome, because it’s happening to them as far as their brain is concerned. That little use of “I” rather than “he” or “she” makes a mountain of difference in the experience. Just imagine… a free trip to Hell, answering the question of one half of the afterlife, without having to pony up one’s immortal soul as part of the bargain.

There are few among us who don’t have that deep, dark little part that is just the teensiest bit curious about Hell, about the seedier side of human endeavor. When a writer offers up the tantalizing promise of feeding that desire, most are willing to take the bait, especially if the price of admission is just a few more words… and a few more… and a few more.

In many respects, that’s what writers need to do: convince the reader to invest the time for just a few more. Writers are crack-dealers when it comes right down to it… feeding brains with a very different sort of drug.

If you’re writing genre fiction, you really do need to consider two things. The first is what and how much of the story you want to expose to the reader. When using first person, the reader should know only what the protagonist knows (with very few exceptions). Using third person opens up doors to getting the perspective of other characters in the story. There are reasons to use both of them, and it’s important for the writer to understand and implement the right one.

The second thing to consider the tone of your language. Word choice is what differentiates your writing from another author’s. It also differentiates noir from tea-cozy from western. There’s a language for damn near every genre, and the people who read that genre speak it fluently. You need to work hard to get your words right, and it’s this process that sets the great writers apart from the good ones… and the bad. The good ones frequently ponder and haggle and angst over a single word. They hold it up to the light and determine if it’s as potent as they need it to be.

So give thought to your words. They can be as potent as crack cocaine or as bland as American cheese.

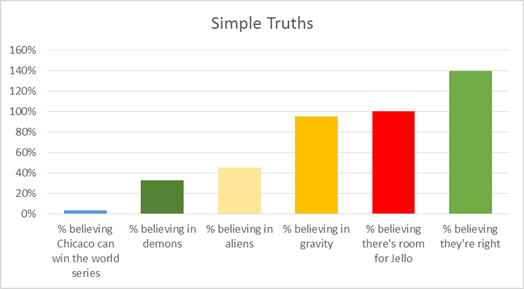

On a side-note, I have crafted this meaningless bar chart below (tongue in cheek, naturally) as both an experiment and an inside joke with my fellow Fictorians.

Q.