When I’m waiting at the bus stop, I see all kinds of people. People with skin colours from cocoa to olive, from toffee to porcelain. People in turbans, in hijabs, in saffron robes. People wearing crosses, pentacles, Stars of David. People of all ages, of all income levels, speaking a variety of languages.

When I’m writing, I want to reflect that kind of diversity in my stories. Unless there’s a specific story-based reason for everyone to look the same, believe the same, and exhibit the same behaviours, I like my fiction to encompass the wide variety of human experience.

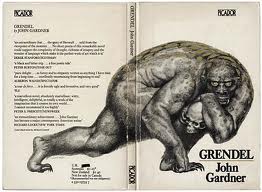

Growing up, I read a lot of stories based on Greek and Roman myth, Biblical personages, fairy tales, Norse legends, King Arthur. The prevalence of these tales made sense in a historical context; these mythologies form the bedrock of modern Western culture. I also found a few precious collections of different mythologies, containing very different personages: Nanebozho, the Ojibwe trickster. Rama, the hero from India. Fox spirits from China. I loved these stories. I’d memorized Cinderella and Snow White. These anthologies provided me with something new, something different. As I grew older, I found that readers, and publishers, are increasingly open to stories featuring a wider diversity of characters, based on legends and mythologies from all over the globe.

Full disclosure time. I’m white, female, of predominantly German ancestry, in a relationship with a man. But I write about all kinds of people. People whose life experiences I cannot base on my own; people whose cultures I was not raised in.

I have to be very careful when I write about these people.

Cultural appropriation is the act of taking something from another culture and using it to suit your needs. To an extent, all cultures in contact mix and borrow from each other. Suburban youth listen to rap songs about life in the hood; Canadian teenagers read Japanese manga; people all over the world go to movies based on American comic book characters. There is, however, a tension in these relationships, particularly when a group with power plunders groups with less power, taking their symbols and distorting them, commodifying them, stripping them of their cultural context and selling them. There is also a tension when people “try to be something they’re not,” particularly when this means they act out of fantasy and idealization rather than a true understanding, or forget their own heritage in the attempt to ape someone else’s. Appropriation can perpetuate stereotypes (think of how Vodun, aka “voodoo,” struggles to be recognized as a religion), water down symbols (it’s hard to take a powerful symbol seriously when you can buy it as a T-shirt or fridge magnet), and confuse with partial understandings and half-truths. Borrowing mythology from cultures not my own is tricky.

And yet, to write only about white, heterosexual people of European ancestry is both dishonest (in that it doesn’t reflect the totality of human experience) and dangerous (in that it insinuates these are the only people worth writing about).

The beauty of fiction is that it demands that I, as a writer, develop the ability to see through my characters’ eyes. I need to know what motivates them, what their dreams are, what their fears are, what their goals are. Their point of view makes sense to them and I need to understand it in order to figure out what they will do next. I need to see them both in the context of their cultures, and as individuals, whose behaviours and beliefs may vary a little-or a lot-from their cultures’ norms.

And so I imagine what it would be like to be a man. Or a lesbian. Or a Hindu. Or an Asian woman. Or someone who lives in the 18th century. I learn about issues these groups face that I do not, in the hopes that my portrayals are based on reality and not on stereotypes. I do my best to portray the myths of other cultures with respect for the context in which those myths were created, and with the reverence I would give to the figures of my own childhood. And I aim to honour, rather than use; to share in, rather than take.

It’s a balancing act, and I can’t please everyone, but when the alternative is to write about a world where everyone is White and European and middle-class and straight, I’ll take some risks, and do some research, to build a world that’s an honest portrayal of the human experience.