Guest Post by Natasha Fondren

The question I get asked most by my clients is this: “What else, other than the text, should I put in my book?”

POD books and eBooks can handle extra pages, images, color, fonts, and content without any cost (up to a certain point, and even with Kindle, it’s marginal). When you’re done writing your book, you want to add content that will first, sell your book, and second, sell your other books.

SELL THIS BOOK

In eBooks, the front matter serves only one purpose: to sell this book to your readers.

In bookstores, readers check out books in this order:

- They catch sight of the cover.

- They turn it over and read the back cover.

- They skim through the appropriate ad pages at the beginning.

- They turn to the first page of the text and read a bit.

With eBooks, it goes more like this:

- They catch sight of the cover on the website.

- They click on the title.

- They check out the average rating.

- They read the synopsis and maybe skim the reviews.

- They download a sample.

It’s important to note that once they download a sample, they haven’t yet bought it. You still have to sell your book with the sample: the first 10% of your book.

CONTENT OF THE SAMPLE

In a traditional book, the opening consists of ad pages, half-title page, title page, copyright page, list of other books by the author, dedication page, epigraph, table of contents, and sometimes acknowledgments.

In an eBook, we want to get rid of everything that doesn’t sell your book because it takes up space in that first 10% of your sample. First, the half-title page, a holdover from printing processes, is completely unnecessary.

The copyright page will not sell your book, nor will it magically prevent piracy. Send it to the back. The acknowledgments, likewise, should be sent to the back.

The list of other books by the author will only sell this book if you have a long list that proves you to be an author who’s had some practice at this. When in the front matter, this list does not sell those books; it only tells the prospective reader that you’ve some experience under your belt.

This list is better at the end, after they finish the book, when they’ll be looking for their next read. Probably they’ve already seen on the website that you’ve written other books, if you have.

The dedication? As interesting as it is to you, it should only stay up front if it’s truly going to hook the reader into buying your book.

The table of contents is accessed through a menu button, so it’s unnecessary to put it up front unless it sells your book, as is the case in nonfiction (telling the reader what is contained in the book) or in some fiction, where the chapter titles are so interesting that they hook the reader.

So what does that leave?

- Ad pages

- Title page

- Epigraph

- Text

Ad pages go first, and these should be an invitation to the reader. While you should take advantage of this opportunity, do not let the ad pages dominate your sample; you want to sell your book to readers, then give them enough of your content to hook them into your story.

There are several potential items that can go in your ad pages (I don’t advise using them all!):

- Reviews: If you have some exceptional reviews from respectable sources, or some funny, tongue-in-cheek reviews, then put two or three at the beginning. More than that, and you’re crowding out your sample.

- Synopsis: Reminding the readers what the book is about is not only a good sales tool, but it’s also one of the ways the human mind learns: big picture to little details. When readers sit down to a book, they want to know what it’s about. While this information may be on the website, they may look at the sample days or weeks later.

- Excerpt: A short excerpt, maybe one or two paragraphs, can work really well. There is an art to selecting just the right paragraph or two–make sure to get lots of feedback from your friends!

- Letter to reader: This is a bit of an old-fashioned technique that I’ve only seen in romance books. It’s been used quite a bit, so it must have some effect. If you pick this, please make sure your note to the reader is super good!

The title page sets the tone for the book, so embed a nice font and have a care for the design. The epigraph, as well, can set the tone for the book.

The text should be inviting: a nice chapter header, a dropcap, possibly some styling in the opening few words all help pull the reader into reading your text. Book design is important!

A PROBLEM WITH AUTO-CONVERSION

If you upload a Word document or use a converter to make a Kindle book, then when a reader opens your book, it will open to Chapter 1, skipping all front matter, ad pages, and even the prologue.

If you hire a professional, they’ll make sure your book opens where you want it to–except the cover. On Kindle, the book generally refuses to open to the cover, unfortunately. (Please do write them and complain, though! Maybe they’ll change it!)

THE BACK MATTER

From the very second your reader reads the last sentence of your book, you need to sell your next book, or your backlist.

The back matter can contain:

Thank You: First up, it’s nice to thank your readers. Make it short and sweet; this is not an about-the-author page. Perhaps a sentence or two informing about (and linking to) what you’ve got in the back matter for the reader. For example:

“Thank you for reading Great American Novel! I hope you enjoyed it. A list of my other books is on the next page, and then the first chapter of my upcoming novel, Pulitzer Prize Novel, to be released in the spring of 2014.”

Second, offer a link to a very simple html sign-up form for your newsletter. (You do have a newsletter list, right?) This should be simple and ugly, easy enough for e-ink browsers to handle, such as my newsletter (free book on Indie Book Production coming soon to all subscribers!). Please note that this doesn’t have to be your only newsletter sign-up page, but for this purpose, you should stick to a sign-up page that can be handled by the worst of browsers.

A List Of Your Other Books: This can go before or after the next section.

Your Next Book: Like the sample, this should be in three parts:

- An image of the cover.

- A quick synopsis or blurb of the book that hooks the reader.

- An excerpt–you can make this substantial, such as the complete first chapter or two.

Other Ideas: I’ve seen some authors put a miniature version of their website in the back, starting with a home page that links to each section of the content that follows. Remember, the page count is nearly limitless, so be creative and give to the reader, and hopefully they’ll give profits back to you!

AND THEN . . .

After that, you can put an about-the-author page, so they know who you are. And then, (finally!) all the stuff you took out of the front matter that doesn’t sell this book or your next book.

Natasha Fondren is the founder of the eBook Artisans. Whether you’re a traditionally-published author looking to make an out-of-print book available, an indie author releasing a self-published eBook, or a publisher looking to make a backlist available, the eBook ArtisansSM is passionate about making your print book or eBook a welcoming and beautiful experience for your readers.

Natasha Fondren is the founder of the eBook Artisans. Whether you’re a traditionally-published author looking to make an out-of-print book available, an indie author releasing a self-published eBook, or a publisher looking to make a backlist available, the eBook ArtisansSM is passionate about making your print book or eBook a welcoming and beautiful experience for your readers.

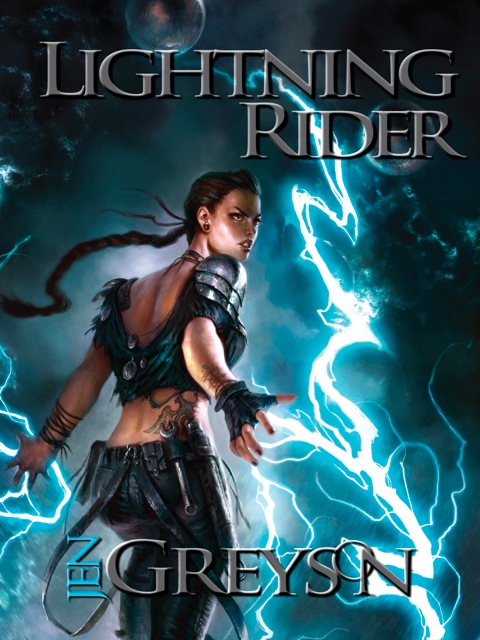

new adult genre was on the rise, in part due to the college age of the main character. My characters haven’t quite fit anywhere other than new adult, and I wanted a smaller publisher willing to go to bat for me and my characters without trying to force them into a different genre (like every other agent and editor I sent it to). TWCS had first-hand experience of launching a mega-hit and I wanted to take advantage of all that in marketing my book, Lightning Rider.

new adult genre was on the rise, in part due to the college age of the main character. My characters haven’t quite fit anywhere other than new adult, and I wanted a smaller publisher willing to go to bat for me and my characters without trying to force them into a different genre (like every other agent and editor I sent it to). TWCS had first-hand experience of launching a mega-hit and I wanted to take advantage of all that in marketing my book, Lightning Rider.