Which scene evokes more tension?

Which scene evokes more tension?

1 – Two master martial artists dueling in a high-flying contest of furious fists?

2 – A child trying to hold a door closed against a huge, rabid dog?

Most people choose number two, even though both contests could likely result in at least one person dying, and the first contest might be more visually impressive. Why is the image of the child against the rabid dog inherently more tense?

Here are a couple of reasons:

- Need a real threat of danger. If we don’t feel the threat, we don’t feel the tension. That’s why humorous confrontations lack tension. (Think most of the fight scenes in Get Smart) In the amazing martial-artist duel, there is a threat of danger, but if both men are equally matched, that threat alone is not enough to ratchet up the tension. We need to add in another element.

- Disparity of force. If the hero is most likely going to lose, we feel more tension. Think David vs Goliath (if we didn’t already know the ending). In the martial-arts example, it’s more tense if the hero is somehow at a disadvantage and more likely to lose. One of the major reasons we feel such tension in the child vs dog example is that the dog holds a huge advantage unless the child can lock the door. Add to that the natural tendency of most people to want to protect children, and the tension grows tenfold.

- Stakes. The higher the stakes, the greater the tension. If the outcome doesn’t matter, there’s no tension. If the hero’s life, or the life of a loved one, is on the line, the tension can shoot through the roof. Add to that the fact that the hero finds themselves at a terrible disadvantage, and the tension ratchets up another white-knuckled notch.

Also remember, often the lead-up to a fight is more tense than the fight itself. In the middle of a fight sequence, we get caught up in the thrill of the battle. Sometimes we get swept away by how cool the fight sequence is and may not actually feel so much tension as we did before the fighting started.

Let’s look at a couple of examples from well-known films. First consider Batman’s final fight with Bane in The Dark Knight Rises. An awesome fight scene, but what filled it to overflowing with tension was the fact that Batman had faced Bane before and lost. The hero faced a very real possibility of losing again, of getting broken and defeated. But he stood up and faced his enemy, despite the risks, and that made us cheer for him, even while filled with nervous tension that made the eventual victory that much more delicious.

Let’s look at a couple of examples from well-known films. First consider Batman’s final fight with Bane in The Dark Knight Rises. An awesome fight scene, but what filled it to overflowing with tension was the fact that Batman had faced Bane before and lost. The hero faced a very real possibility of losing again, of getting broken and defeated. But he stood up and faced his enemy, despite the risks, and that made us cheer for him, even while filled with nervous tension that made the eventual victory that much more delicious.

A nother great example is in The Matrix in the fight scene between Neo and Mr. Smith. The entire movie sets up the tension, with the viewers being told and demonstrated over and over again that the Agents were impossible to beat and that everyone who had ever tried to stand against them had died.

nother great example is in The Matrix in the fight scene between Neo and Mr. Smith. The entire movie sets up the tension, with the viewers being told and demonstrated over and over again that the Agents were impossible to beat and that everyone who had ever tried to stand against them had died.

Then Neo is forced into a position where he chooses to fight anyway, and the tension is awesome. The resulting fight scene is super-epic, our enjoyment magnified by that huge tension build-up.

An important note is that the stakes need to be believable. For example, in the recent hugely-popular movie Avengers Civil War, the tension didn’t work for me because I felt he set-up for the fight between heroes that I both thought were great wasn’t done well. I didn’t believe that they had sufficient justification to try killing each other, so the stakes felt hollow, and the tension weak. The fight scenes were well choreographed, but they lacked true tension because they felt forced.

And sometimes the most tense scenes are the ones where the hero and the antagonist are forced to be polite to each other, but are yearning to leap at each others’ throats. The tension in such pre-fight confrontations can be dialed up to delicious levels.

One great example is Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark, when Indy meets his arch rival, Belloq, in the café, right after the scene where we’re led to believe the leading lady, Miriam, just died. The conversation is laced with insults, and the threat of fatal violence bubbles just under the surface. It’s a great example to study.

So, let’s assume we’ve got a great confrontation planned, with serious stakes that have been well established, with a very real threat of danger, and with the bad guy holding every advantage. It’s still all too easy to destroy the tension by failing to manage the pacing, or by including too many details.

Conflicts have to move along at an increasing tempo. They can start slow – think the epic sword duel in The Princess Pride – but the tempo must increase, then increase some more, that rising tempo helping to raise the tension level.

Conflicts have to move along at an increasing tempo. They can start slow – think the epic sword duel in The Princess Pride – but the tempo must increase, then increase some more, that rising tempo helping to raise the tension level.

During a fight scene is not the time to suddenly pause to discuss the finer details of craftsmanship of the weapons being wielded, what types of metals were used in building them, or the history of their use. If fighting with guns, don’t pause to discuss the pros and cons of different calibers, or compare the ballistics. Nor is it the time for long monologues or exhaustive self-analysis. Such detours kill the tempo and pacing and snuff out the tension. If such details are important, include them somewhere prior to the fight so the reader already understands.

One must also be careful not to share too many details. Imagine trying to read a detailed blow-by-blow account of an epic martial-arts duel. Such a chronicle would run for pages and pages, and would bore the readers to tears and destroy any chance of maintaining pacing or tension.

So pick the most important details and focus on those. Paint the other aspects of the fight with broad strokes, including enough sensory detail to lock the reader into the scene. Make sure the blocking is clear so the reader understands the physical location and how the combatants are moving within the space, but don’t describe every punch, swing, or the trajectory of each bullet. Then dive deep into the critical final sequence, slowing the action and increasing the level of detail so the reader is absolutely dialed in to what is happening. This will increase tension even more, as well as the pay-off.

If those moments are properly set up, they will explode across the page with increasing tempo, careful choices of details, focus on the stakes and the ultimate conclusion, resulting in amazing scenes that will linger in readers’ minds long after they reach the last page.

About the Author: Frank Morin

Frank Morin loves good stories in every form. When not writing or trying to keep up with his active family, he’s often found hiking, camping, Scuba diving, or enjoying other outdoor activities. For updates on upcoming releases of his popular Petralist YA fantasy novels, or his fast-paced Facetakers sci-fi time travel thrillers, check his website: www.frankmorin.org

Frank Morin loves good stories in every form. When not writing or trying to keep up with his active family, he’s often found hiking, camping, Scuba diving, or enjoying other outdoor activities. For updates on upcoming releases of his popular Petralist YA fantasy novels, or his fast-paced Facetakers sci-fi time travel thrillers, check his website: www.frankmorin.org

Honestly? I’ve never thought about tension while writing. I’ve thought about conflict a whole lot: overarching conflict, conflict between characters, conflict with the environment, etc. But I’ve never framed it in my mind as “tension.” After some thinking, I decided it wouldn’t be quite right to offer advice about something that I don’t tend to think about while writing. However, I have noticed it while reading. So in lieu of offering advice, I’ve put together a list of memorable stories that created tension in a very unique way that may help you in your own writing. The fun of creating tension doesn’t have to be all your characters’ doing. By honing in on your narrative voice, you can create tension between you and your reader using a variety of techniques.

Honestly? I’ve never thought about tension while writing. I’ve thought about conflict a whole lot: overarching conflict, conflict between characters, conflict with the environment, etc. But I’ve never framed it in my mind as “tension.” After some thinking, I decided it wouldn’t be quite right to offer advice about something that I don’t tend to think about while writing. However, I have noticed it while reading. So in lieu of offering advice, I’ve put together a list of memorable stories that created tension in a very unique way that may help you in your own writing. The fun of creating tension doesn’t have to be all your characters’ doing. By honing in on your narrative voice, you can create tension between you and your reader using a variety of techniques. In the classic book One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez sets up tension in the first half of his book by dropping the same line over and over: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía remembered…” Instantly, the reader questions this. Aureliano before a firing squad? How did he get there? Also… Colonel? When does he become a Colonel? With this line, the author continues to keep these questions fresh in the reader’s mind, and the reader continues on with the book in order to get the answers to those questions.

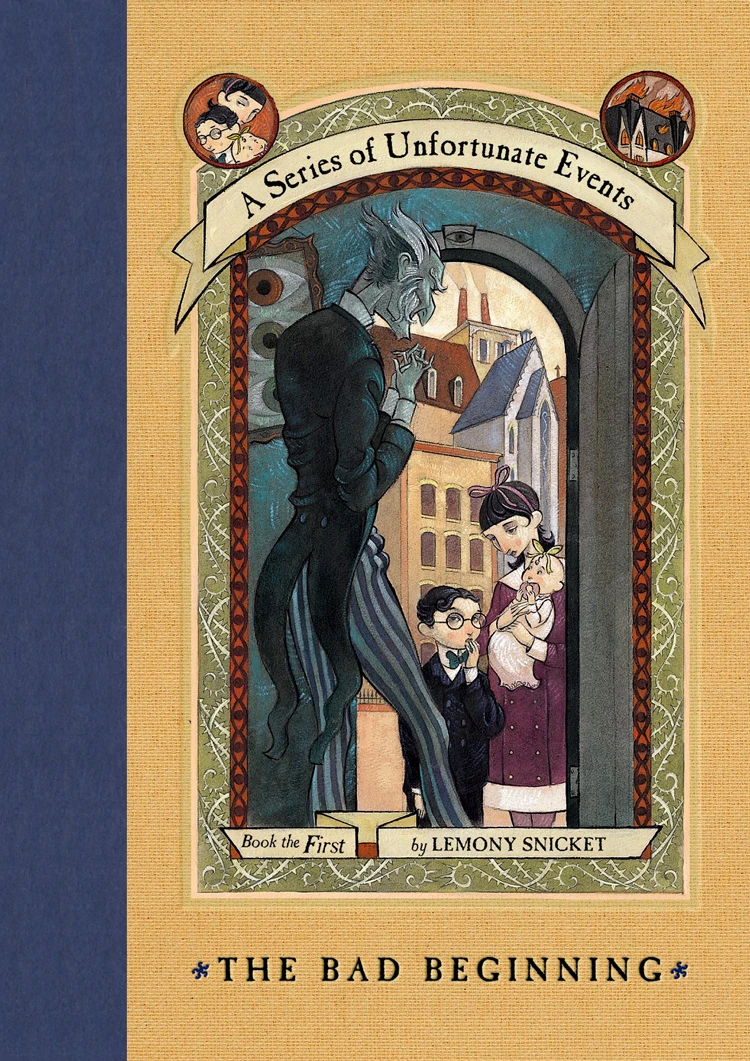

In the classic book One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez sets up tension in the first half of his book by dropping the same line over and over: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía remembered…” Instantly, the reader questions this. Aureliano before a firing squad? How did he get there? Also… Colonel? When does he become a Colonel? With this line, the author continues to keep these questions fresh in the reader’s mind, and the reader continues on with the book in order to get the answers to those questions. In one of the darkest children’s series out there, Lemony Snicket (Daniel Handler) adds a warning to the reader at the beginning of every book. In the very first book, he lays the land:

In one of the darkest children’s series out there, Lemony Snicket (Daniel Handler) adds a warning to the reader at the beginning of every book. In the very first book, he lays the land: This technique is a favorite among Literary Fiction authors and moviemakers. The author has one character telling the story as they remember it, allowing them to be the narrator. However, the switches from past to present is up to the author. That means right when something happens, the author has the power to pull back to present time, have the narrator reflect for a time, and then go back into the action. This undoubtedly drives some readers nuts, but can we deny it causes tension? Nope! An example of this would be Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, where our narrator, Cal, starts most chapters in the present, and then switches back to telling his grandparents’ and parents’ stories. The reader becomes anxious to see what’s going on in the present, and yet is forcibly taken to the past instead. This, in the best cases, builds tension by way of anticipation.

This technique is a favorite among Literary Fiction authors and moviemakers. The author has one character telling the story as they remember it, allowing them to be the narrator. However, the switches from past to present is up to the author. That means right when something happens, the author has the power to pull back to present time, have the narrator reflect for a time, and then go back into the action. This undoubtedly drives some readers nuts, but can we deny it causes tension? Nope! An example of this would be Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides, where our narrator, Cal, starts most chapters in the present, and then switches back to telling his grandparents’ and parents’ stories. The reader becomes anxious to see what’s going on in the present, and yet is forcibly taken to the past instead. This, in the best cases, builds tension by way of anticipation.

It’s important that things keep getting in the way of the characters pursuing each other. If they were so close to each other that they can smell each other’s toothpaste, have someone (such as the comic relief character) stumble into the room just microseconds before their lips were going to touch. Have the Sklorr set up a nice date with her human girlfriend, only to have the transport tube break down on the way to the restaurant. The human will be angry and wonder if her date stood her up, while the Sklorr will be frustrated that her romantic date she planned out in detail was ruined because of a tiny component she forgot to replace when she worked on the tube system this morning.

It’s important that things keep getting in the way of the characters pursuing each other. If they were so close to each other that they can smell each other’s toothpaste, have someone (such as the comic relief character) stumble into the room just microseconds before their lips were going to touch. Have the Sklorr set up a nice date with her human girlfriend, only to have the transport tube break down on the way to the restaurant. The human will be angry and wonder if her date stood her up, while the Sklorr will be frustrated that her romantic date she planned out in detail was ruined because of a tiny component she forgot to replace when she worked on the tube system this morning.