I hear from other authors or prospective authors that nothing is quite as intimidating as a blank page.

I won’t speak for everyone, but this simply isn’t the case for me. I love a blank page. A blank page represents the infinitely possible. A blank page represents freedom. When I have a blank page, I can fill the thing with whatever I want. It’s hope, it’s potential beauty, it’s raw creative space. I love a blank page.

For me, there’s nothing quite as intimidating as a page filled with a terrible story that I have written.

For me, there’s nothing quite as intimidating as a page filled with a terrible story that I have written.

You see, sitting down and drafting is easy. It’s the thing we all love to do. It’s the funnest part of writing a thing. It’s what makes NaNoWriMo so popular (and so problematic for some) Throwing down raw, fat word counts is, without a doubt, simply a joy.

Fixing a broken story? That’s hard.

So, let me take you back to the fall of 2015. I’m writing this story for a little anthology called Horseshoes, Hand Grenades, and Magic. I’m not going to lie–the call for this thing was weird. My task was to write a story wherein “close is good enough.” That’s a really esoteric theme, and I know I’m not the only author that struggled with it.

See, I got this idea in my head. A thief breaks into a vault and then has to use the enchanted items therein to get back out, only he has no clue what those items do. Sounds like a fun little story, right?

Nope. Nightmare.

I ended up with about four thousand words of me repeating the same joke over and over again as told from the persepective of a main character that, by virtue of this joke, had almost no agency. It. Was. Terrible. I haven’t drafted a story this bad since high school. I gave it a day, read the thing, and cringed.

I ended up with about four thousand words of me repeating the same joke over and over again as told from the persepective of a main character that, by virtue of this joke, had almost no agency. It. Was. Terrible. I haven’t drafted a story this bad since high school. I gave it a day, read the thing, and cringed.

My wife, who usually takes the second pass on our stories, tried to calm me down. She’s a lovely woman, and her initial reaction was “Frog, you say everything is terrible when you write it.” And she’s right, but I tried to impress on her how much I really meant it, this time. Still, she insisted that she should read it and take the second pass, as is our normal wont.

I don’t actually think she finished that first read. Very, very quickly she returned, and this time with a different attitude.

“Okay, this time you’re right,” she said. “It sucks.”

Now, we’re all going to have off days. We’re all going to muff it a time or two. Nobody hits a home run every time they step up the the plate. Insert failure platitude of choice here.

But I want you to learn from my mistake. Screwing up the initial draft was bad, but not unforgivable. It’s what I did next that really sets this baby apart in the annals of Frog’s terrible mistakes. It’s my response to writing this malformed chunk of text that marks this experience as being just slightly worse than trying to shave my beard with a cheese grater.

I tried to fix it.

I spent a month. An entire month’s worth of writing time. An entire month during which I could have been working on a novel, or churning out four other short stories. No, I threw good time after bad, and I tried to polish this turd until it shone. I tweaked the language, I moved paragraphs about, I tried everything I could think of to make the story readable, but nothing I tried worked. You know why? Because it was a bad story. It wasn’t bad writing, it wasn’t bad grammar or bad structure. It was a bad story. No matter how I told it, it was going to suck. But I latched onto the thing like a weight and let it drag all of my writing goals down with me for a month.

It was my wife that saved me. After a month went by, you know what she did? She handed me a blank page. She sat me down and told me to stop thinking about the way I had written the story, and to start completely over from my original concept.

It was my wife that saved me. After a month went by, you know what she did? She handed me a blank page. She sat me down and told me to stop thinking about the way I had written the story, and to start completely over from my original concept.

Two days later, the story was written, revised, and sent to the editor. It’s still got the same core concept as the original version, but this time it also has a story. You know, a whole plot arc, with dialogue and motivations and all that jazz that we put into stories that make them not suck. This second version is good; I’m actually pretty proud of it.

But mostly, when I did a reading of it at the last convention I appeared at, it made me think of that full month of pain in the fall of 2015 where I refused to cleanse a bad story with fire. Learn from my mistake, oh ye reader of writing blogs. Learn that sometimes, when you just can’t find a way to fix what you’ve done, the best thing to do is burn it to the ground and get yourself one of those blank pages everyone keeps talking about.

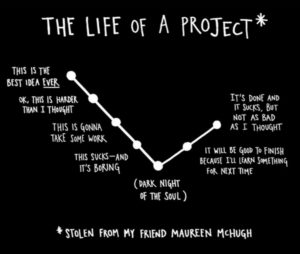

You know when you’re knee deep in a project and then you get that shiny new idea? And you’re like, “But Brain, I don’t write Historical Fiction. You must have me confused with a better brain that likes to research things to death.” And yet, you love the idea so much, you decide, maybe one day, you’ll write that shiny idea into a book or short story, or *gulp* a series.

You know when you’re knee deep in a project and then you get that shiny new idea? And you’re like, “But Brain, I don’t write Historical Fiction. You must have me confused with a better brain that likes to research things to death.” And yet, you love the idea so much, you decide, maybe one day, you’ll write that shiny idea into a book or short story, or *gulp* a series. Read.

Read.