So you want to write an epic sci-fi or fantasy series…

Been there, done that.

I know authors who have written double-digit books in their series. I suppose that’s a great thing if it’s making money. But to me there’s a sort of hidden trap in creating a series that becomes self-perpetuating and endless. Part of that may just be my own proclivities as a reader. In general I find three or four books to be about as long as even the best writers can keep my interest in one story, one protagonist, and/or one set of supporting characters.

I just have too much interest in other stories to keep going back to that same water hole.

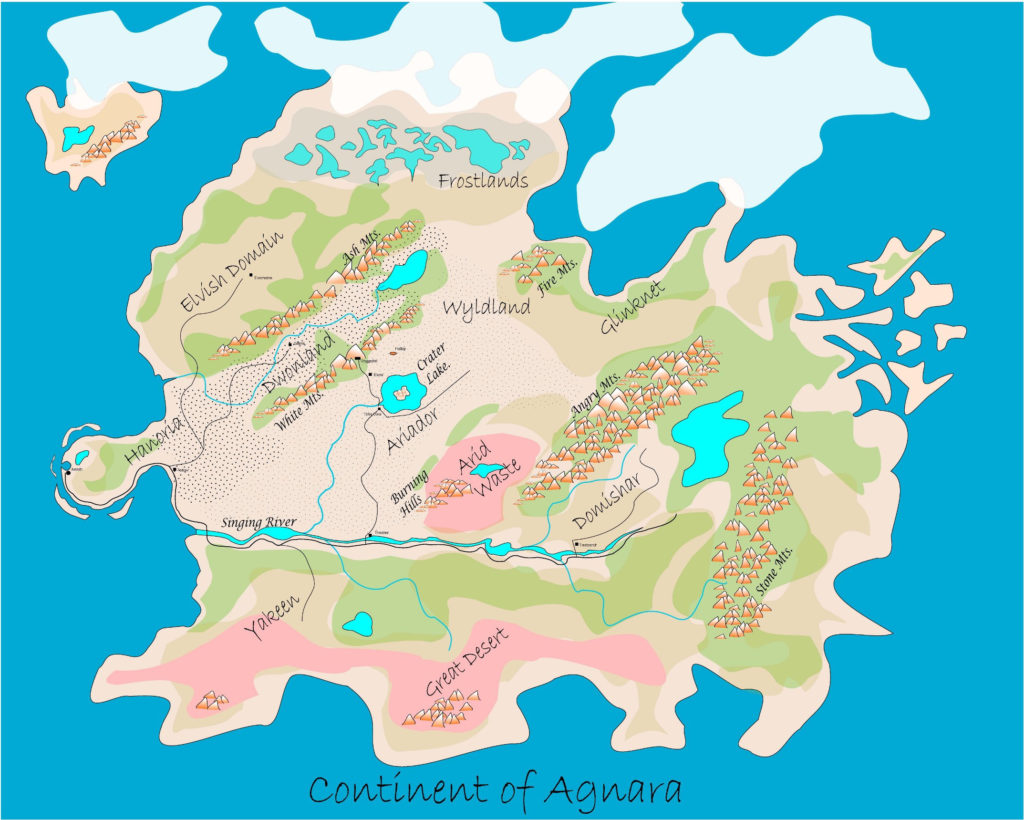

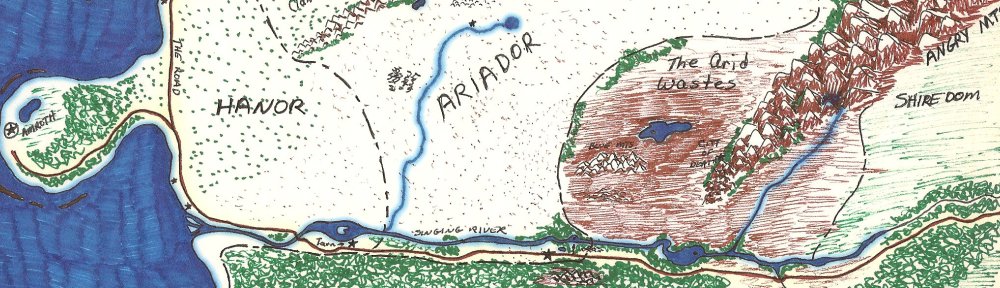

So when I started my War Chronicles epic fantasy series, I very deliberately set a story line that would be finished after three, maybe four books. I had no intention or desire to be writing War Chronicles books for years. I wanted to write other stories.

Now, had that series taken off like Harry Potter, and publishers were flying to my home to shove money in my mailbox, maybe I’d have a different perspective. But that didn’t happen, so I’m happy with what I did earn on my first series, and am glad that I have since written a sci-fi novel, and am now working on a contemporary murder mystery novel. From the first time I decided to pursue writing as a hobby and (hopefully) a career, I wanted to keep my options open and write widely in different genres.

I think that will make me a better writer in all genres.

Now, from a career perspective, maybe that’s a mistake. Maybe sticking with one sub-genre for my entire career might be a better way to establish a loyal fan base and churn out stories that are eagerly anticipated by those fans.

But even if it is, I’m enjoying my foray into contemporary murder mystery. Who knows, my next book might be a romance novel.