A guest post by R.R. Virdi

It’s a cool night, the sort you’d find in late Autumn. You’re in the dark and gritty underbelly of your city rooting out crime and all without a weapon. What’s left?

The concrete below you. Brick walls. Maybe the unforgiving and cold metal of the railings lining the old apartment buildings. Enter the 2008 film, The Spirit, an adaptation of the Frank Miller comic. We’re brought to Central City on a nighttime patrol along with the fictional character the movie is named after. It’s one heck of a showcase on how setting is more than just a place.

We’re treated to a near-romantic inner monologue about the relationship The Spirit has with his city. It’s his weapon, a tool to sleuth through, fight back with, and it’s really a she, and she’s one great character.

Rewind back to your early schooling. You’re taught that setting is a place. You’re told how to fill out neat little boxes and describe your surroundings a bit too literally. There’s no life. Everything’s a compilation of objects. That’s it.

Or is it?

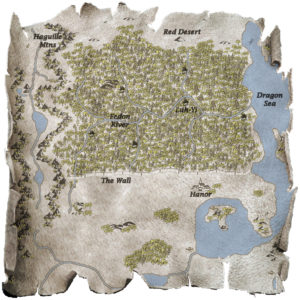

Setting is malleable—a living thing. One of the greatest places to see that as a working example is the cities littering the world around you. But, if that’s too much, try urban fantasy. From superhero comics, to novels starring magically powered protagonists, cities offer a certain complexity and variable use to the old writer’s tool of setting.

What do I mean?

Well, take New York’s favorite wall crawler, Spiderman. The boroughs of New York are microcosms of the world. Bustling hives of activity that add color and vibrancy to Spiderman’s life. But through those throngs of people are endless and often unseen dangers. There’s an undertone of possible threat each and every time Spidey is navigating the concrete jungle on the ground or in the air.

Urban fantasy relies heavily on its setting to put in place the tone of the series. You city is your character. It’s your maze, a living history, and a multi-tool. You can do nearly anything you want with it.

When you have a city, well, you know have all the sorts of people and institutions you’d expect with it to work with. Everything from billionaire CEOs as characters who’d call it home, to the less fortunate. Now, push either or both of those sorts of people to a life of crime. Congrats, you’ve now birthed someone like Gotham City’s Black Mask, or, Joe Chill.

Cities are melting pots of people and architecture that give you an endless literary sandbox to work in. Imagine the long, open streets of New York’s grid system. Pretty nice place to set a foot chase, even a car one. Great line of sight, tons of bright lights and activity. Now imagine you’ve taken a few wrong turns and are winding down unfamiliar alleyways.

Oops.

Great place for an ambush. Maybe cornering your target. Too bad you weren’t carrying a weapon to defend yourself. I hope you’re good with your hands. And if you are, you just might find yourself in a handy place to be. Hard surfaces can be your friend. Cities have no lack of those.

Navigating them can be a chore or an adventure, and in all of that, a bit dangerous if you want it to be. Within this page, you’ve already seen one city be a weapon, a threat, a multi-tool for different scenes and pacing, whether high pumping chases or heart pounding ambushes, to a home that shapes its people into protagonists or villains.

Urban fantasy relies on that. Jim Butcher’s Dresden Files is the perfect example. Bring on Chicago, an endlessly diverse city with a history of dirty politics and money, tough law enforcement, a forgotten under town, and a great balance of towering concrete monoliths and everyday suburbia as its landscape.

What can’t you do with all of that?

It’s a place that could be home to a hardworking blue collar father raising his kids in the suburbs. And at the same time, the city that birthed an iron-hard gangster who clawed his way to the top of the criminal underworld. One city, two different people coming out of it.

It nurses the beautiful and opulent Gold Coast, where some of the human and paranormal elite make their wealth and power known. The second you show up, you get the hint. It sets quite a tone. It also changes the battlefield. Slugging it out in a skyscraper business center is way different than the open ground of a suburb. But, if you’re Chicago’s resident wizard, you’ll be called on to do both, and more.

You’ll be asked to lurk and skulk through alleys, boxed in both sides with one way out ahead of you, and one behind. But, it’s not that easy keeping an eye over your shoulder in that setting and one on what’s before you. Nice way to get trapped or attacked.

Moving through one city environment allows a creator to control the pace however they want because cities offer it all. Sluggish public transport, leaving you crowded, pressed for time and up for danger, should the writer feel like it.

Enter any number of thriller novels and movies with a close quarters fight on a subway.

Or, let’s cut to hoofing it on foot through massive crowds on the streets. Always great if you need to eat up some of your character’s time. And through it all, it’s an experience. Cities always come with a five-way sensory assault. Ones that can go overboard.

Blitzing and jarringly bright colors, ear-rattling sounds, sometimes smells you wished you couldn’t pick out—ones you can almost taste. Not to mention the air that seems to cling to you like a second skin or a thin film of hot breath and unclean air.

There’s a certain set of voices to each city. Blaring traffic, clamoring people, chittering electronics, and let’s not forget construction.

Yeah, cities are certainly a setting, but they’re a living one. They’re something that you can’t really pin down. They’re something to be experienced and are in reality, entire world’s of their own. They certainly have enough slices of our globe nestled within them.

Setting isn’t just a place, it’s a tool. It can be as strong a character as you want it to be. Heck, cities already have names and reputations, what more do you want? They’re alive. Do something with them. Give them a chance to pop out and shine.

Want to really get into the mind of your reader, make sure you choose one heck of a place for your characters to live and act. If you do, that place may end up living on in the reader’s mind long after they close that book.

Cities, you can end up lost in them, and in more ways than one.

R.R. Virdi is the Dragon Award—nominated author of The Grave Report, a paranormal investigator series set in the great state of New York. He has worked in the automotive industry as a mechanic, retail, and in the custom gaming computer world. He’s an avid car nut with a special love for American classics.

The hardest challenge for him up to this point has been fooling most of society into believing he’s a completely sane member of the general public. There are rumors that he wanders the streets of his neighborhood in the dead of night dressed in a Jedi robe and teal fuzzy slippers, no one knows why. Other such rumors mention how he is a professional hair whisperer in his spare time. We don’t know what that is either.

Follow him on his website. http://rrvirdi.com/

Or twitter: @rrvirdi or https://twitter.com/rrvirdi