If you are a fan of long, epic fantasy, there are plenty of series that either you or others will describe as “un-adaptable.” They even said it about A Song of Ice and Fire at one point. In fact, George R.R. Martin, disgusted by Hollywood at the time, specifically wrote the series to be impossible to adapt. But as big-budget as Game of Thrones has wound up being, it has one major advantage over a lot of other fantasy epics: very little magic, and none of it used day-to-day. That lets the creators splurge on big moments where needed. Other series like The Wheel of Time, where magic is used almost constantly from early on, would be much costlier to adapt.

If you are a fan of long, epic fantasy, there are plenty of series that either you or others will describe as “un-adaptable.” They even said it about A Song of Ice and Fire at one point. In fact, George R.R. Martin, disgusted by Hollywood at the time, specifically wrote the series to be impossible to adapt. But as big-budget as Game of Thrones has wound up being, it has one major advantage over a lot of other fantasy epics: very little magic, and none of it used day-to-day. That lets the creators splurge on big moments where needed. Other series like The Wheel of Time, where magic is used almost constantly from early on, would be much costlier to adapt.

But there is a way.

The Wheel of Time is reportedly heading toward a television adaptation. I would like to humbly suggest that any attempt to adapt such a vast and sprawling series do so via animation.

Animation doesn’t get used as an adaptation technique all that often. Despite The Simpsons being almost 30 years old (ugh), it still often carries a stigma of being “for kids.” Star Wars has bucked the trend, with the animated Clone Wars and Rebels scoring well with both kids and adults. And no wonder, for animation has several advantages over live-action, two of which factor heavily into adapting a sprawling, multi-volume epic.

- Budget Leveling:Let’s say you’re making Star Trek: The Animated Series, and you are lamenting the fact that the aliens in Star Trek almost always look like humans with various ridges on their faces and heads. There were very real budgetary constraints on the low-budget live show when it aired in the 1960s, and humanoid life was the easiest alien life to achieve, because actors in makeup were easier to manage than puppets or nascent visual effects. But in an animated series, Captain Kirk costs as much to draw as an alien that bears no resemblance to a human. Thus do you get Lieutenant Arex, the three-armed, three-legged, long-necked Edosian who would have been impossible to realize in live action at the time. Thus also do you get scenes with the characters wearing “life support belts” that enable them to explore areas of open space and hard vacuum, because one setting costs as much to animate as another, giving the writers far more options to play with.So imagine an adaptation of The Wheel of Time as an animated series. The budget for visual effects is the budget for the entire show. Animating Rand al’Thor battling Ba’alzamon in the sky above Falme costs the same as having them fight in a forest. Having characters channel (use magic), something that a live action series would have to depict sparingly, could be treated as the everyday occurrences they were in the books.

- Actor Aging:Above I discussed the first big problem in adapting sprawling epics, the “epic” part. Now I’ll tackle the second: sprawl. Specifically, I’m referring to temporal sprawl, or rather, the amount of time it takes to translate multi-volume epics to the screen. For reference, let’s look at Harry Potter. The series spans seven years in the lives of the characters over seven volumes. The movies (there are eight of them in the main sequence) were released over ten years. Now believably saying that child actors aged only seven years when in fact they aged ten isn’t difficult. Audiences have long been conditioned to accept older actors as younger characters.But consider this: the events of The Wheel of Time take place over the course of approximately three years. The series is fourteen books long. Even with the inevitable paring down of the number of seasons, it’s a much taller order to convincingly look as though only three years have passed when a decade has.

Or, you could not even bother, because animated characters can stay the same age forever, and when the only element of the actor required is their voice, you needn’t limit your casting decisions by adding a “must look young for their age” requirement. To once again reference The Simpsons, perpetually ten-year-old Bart Simpson is voiced by 59-year-old Nancy Cartwright.

I would love to see more “un-adaptable” series I love find new lives in animation. It’s the best way of bringing a complex, effects-heavy story to life without cutting it to the bone or rendering it a pale shadow of its true self. Here’s hoping that more creators will follow the lead of Star Wars and Star Trek and explore this sadly underutilized adaptation option.

Leveraging your IP into a film or miniseries adaptation is one of the best ways to make money as a writer. Not only can you get the income from licensing your rights, but having a major motion picture or miniseries made will give your works access to a much larger audience. The phrase “based on a bestselling series” is good for both sides of the business. It attracts attention to the movie, but it will also give a healthy boost to your book sales leading up to the release.

Leveraging your IP into a film or miniseries adaptation is one of the best ways to make money as a writer. Not only can you get the income from licensing your rights, but having a major motion picture or miniseries made will give your works access to a much larger audience. The phrase “based on a bestselling series” is good for both sides of the business. It attracts attention to the movie, but it will also give a healthy boost to your book sales leading up to the release. However, film has significant advantages in its ability to employ complex visual elements. As authors, we rely on the power of our language to inspire our audience’s imaginations. Film, on the other hand, relies on the skill of the special effects, costuming, and set design teams as well as the training of the actors. When you write a book, be sure to feed those teams with strong, iconic visuals. Furthermore, a five second panning shot can show the thousands of tiny details that would take an author five pages to describe. You get the same effect without having to worry about slowing down pacing.

However, film has significant advantages in its ability to employ complex visual elements. As authors, we rely on the power of our language to inspire our audience’s imaginations. Film, on the other hand, relies on the skill of the special effects, costuming, and set design teams as well as the training of the actors. When you write a book, be sure to feed those teams with strong, iconic visuals. Furthermore, a five second panning shot can show the thousands of tiny details that would take an author five pages to describe. You get the same effect without having to worry about slowing down pacing. Though many of Dresden’s spells were fantastic, they were also remarkably low budget. Making the pentacle necklace glow? Not hard. Blasts of fire would take more skill, but can be done in a number of film editing softwares. As can Bob’s glowing campfire sparks.

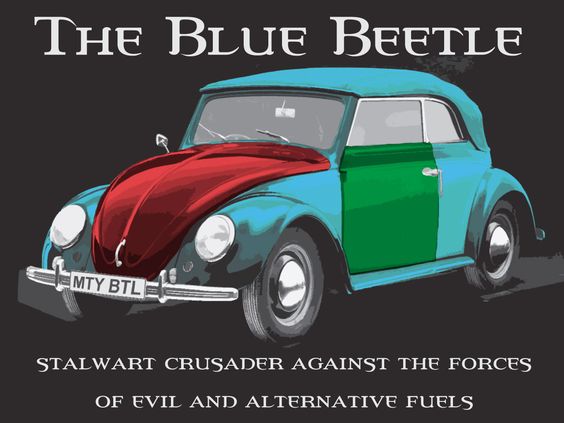

Though many of Dresden’s spells were fantastic, they were also remarkably low budget. Making the pentacle necklace glow? Not hard. Blasts of fire would take more skill, but can be done in a number of film editing softwares. As can Bob’s glowing campfire sparks. For example, the directors of the Dresden Files TV series chose to eliminate the beloved Blue Beetle in favor of a Vietnam era jeep. While the Blue Beetle provided good comic relief in the books, it would have been an extremely difficult set piece to shoot. The director’s camera angles would have been severely limited by how small and enclosed the vehicle was. The only way to get around this problem would be to have multiple Beetles – the first for exterior shots, and a second that was partially disassembled accommodate to the cameras for the interior shots.

For example, the directors of the Dresden Files TV series chose to eliminate the beloved Blue Beetle in favor of a Vietnam era jeep. While the Blue Beetle provided good comic relief in the books, it would have been an extremely difficult set piece to shoot. The director’s camera angles would have been severely limited by how small and enclosed the vehicle was. The only way to get around this problem would be to have multiple Beetles – the first for exterior shots, and a second that was partially disassembled accommodate to the cameras for the interior shots.