April 2018 was a great month to learn about the various ways we can approach the art of revision. Yes, it is an art. Although there are skills we all need to employ, like the skills of grammar, understanding theme, knowing how to revise a scene, knowing how to choose beta readers and accept their feedback, and so much more, all those skills must be combined to form our individual approach or art to revision.

Please come back to these posts any time and find those gems of wisdom which will help you create your best ever story told! For easy reference, I’ve summed up the posts and have added links to them. Cut and paste this blog into your Revisions folder so that you have an easy reference to answer any questions you may have regarding revisions.

Oh, and one last REALLY IMPORTANT note: let it rest, have fun, party and reward yourself for a job well done and then when you are ready, buckle down, and just do it! Revision can and should be a rewarding process.

In, Conquering First Draft Fear: How to Proceed with the First Round of Revisions, Kristin Luna tells us that time away from the manuscript gives us the ability to rise past the subjective fear and to recognize what is and isn’t working. All our fears about revisions are details – and in the details! You know you still love the story and you will do the necessary work. Kristin’s most important piece of advice regarding revisions – Just. Do. The. Revisions.

Mary Pletsch’s three part series on beta readers is a must read. – Beta readers are not editors although their feedback is invaluable; you may want to include non-disclosure agreement; always be sure they know your deadline; beta readers aren’t meant to be cheerleaders who are emotionally supportive. They need to be upfront and honest about what is and isn’t working and we as writers need to know why. Be clear what you don’t want (grammar, for example) and what you do want (plot, dialogue or character issues). Check out: What is a beta reader? Part 1 of 3; Beta Reading and Emotional Minefields (Part 2 of 3); and Beta Reading and Emotional Minefields (Part 2 of 3)

Being a couch potato is a good thing, Kim May tells us in Couch Potato Time For Health and Profit, Treat yourself for finishing the first draft and then do nothing for at least a week to give your creative side time to rest and so you don’t end up resenting your work.

Author and Editor Susan Forest – After you receive comments from your beta readers, how do you handle their feedback? Put their advice into two columns: line edits and global revisions. Phrase all comments in the positive. For example, even if you agree that the protagonist is weepy and weak, revise that comment to something more positive like Angela should stand up for her position. Divide the comments into small workable batches and note them at the beginning of each scene before you revise. For more great tips read Organizing Critique Comments for Implementation .

In When A Pantser Revises, Chris Marrs likens a pantser’s first draft to putting together a jigsaw puzzle and in the process of putting the puzzle together, a picture emerges in a way you haven’t dreamed. Pantsing the first draft gives free license to the imagination from where wonderful gens emerge.

Knowing where your writing is strong and where you tend to gloss over or not do as well in the first draft is a very cool approach to revising your novel. In Revising in the Wild West, David Heyman candidly talks about his strengths and weaknesses in the first draft and his approach to creating a better novel. Having the first draft read aloud to him helps David catch things he’d miss visually. Then, he looks for three things: things he does well (yay!); those he doesn’t do well; and things he doesn’t do at all.

Jo Schneider’s approach to having finished the first draft is a fun one – party! In This is Only the Beginning, Jo explains that as an outliner, she writes the first draft quickly and then after a rest period is truly excited to discover what unplanned things happened to her characters. She makes bother reader critique notes when she reads the first draft along with specific plot, scene and other notes. After that, it’s time to revise the outline and see what awesome hybrid has been created.

How do I know it’s a Rough Draft? It’s dull. Very dull, in fact. Fiction editor Barb Galler-Smith knows when an author has a story is ready to be polished for publication when it propels her from start to finish and she can over look minor errors. Drafts vary – there’s the UGLY draft which consists of everything as it came out of your head, the ROUGH draft where you’ve cleaned up the manuscript as much as you could, then after you’ve received feedback from your beta readers and made those corrections, you have your FIRST draft completed which could also be your SUBMISSION draft.

In Revisions, edits and proofing. The real work of writing., Sean Golden explains that it’s easy to be in the creative zone and to write the first draft but the real work is in the number of specific passes Sean makes to get his manuscript ready for an editor. First, he looks for the big things like character arc, conflict and plot holes. Then it’s passes on dialogue, contractions, passive and active voice.

Like a poker player, every writer has tells which make his voice unique but some of which are bad ones and need to be culled. In Your Writing Poker Face, Gregory D. Little explains that it’s important to understand our tics and the habits we fall into because then we have an opportunity to not only correct the bad ones, but also to celebrate those which make our writing voice unique. But best of all, it helps us avoid self-plagiarism where we tell the same stories, explore the same themes, and the similar characters over and over again.

Frank Morin reveals the agony of receiving feedback from editors in Embracing the Pain – Receiving Editors’ Feedback. However, the purpose of feedback is to make the story fulfill its potential and a writer’s growth comes from constructive criticism. Although much needed, it can still be a painful process Embracing the Pain – Receiving Editors’ Feedback The joy of revision comes after Frank’s embraced the feedback, accepted responsibility for the flaws and he embraces the work and the story truly becomes amazing.

Editor and author Adria Laycraft shares her 10 steps to take before seeking critiques from others. Highlights from her post include: writing a back cover blurb and a synopsis to know the story better; drawing up plot points, looking for tension, and assessing if scenes further the plot. Oh yes … let that manuscript rest a while! To read more, check out 10 Steps After “The End”

This month I wrote about three things we can do to understand out story and to approach revision systematically:

1) In Before You Revise, Know Your Story – 5 Simple Steps, the big takeaways were to write your About Statement in one line and change it into a question. If you’re climax addresses this question, you’ve been consistent with your theme and purpose. Create a scene by scene outline which will help you see if the story is cohesive and if each scene is doing its work;

2) If you’re writing a series, don’t revise your first draft until you’ve thought about and plotted your second novel, or at least the series arc. It’s too easy to perfect the novel and later, and tragically after publication, discover that there were certain things that should or should not have been included. So, Don’t Revise – Plot the Next Novel!; and

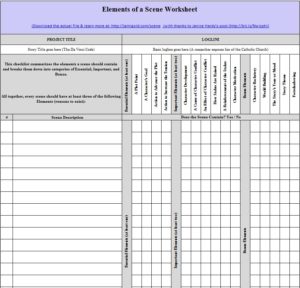

3) What does it mean to revise a scene and how do you do that? That’s the question I answer in How to Revise a Scene which includes all steps from identifying your scenes, to their role in the story’s structure and how to assess specific scene impact.

We hope you’ve found something to help make the revision process a little easier, more fun and rewarding. Happy revisions!