My Year in Review: A Tale of Disappointment, Fear, and Murder.

By L.J. Hachmeister

2016 started off with a bang. I just finished my first out-of-state convention with a group of established authors, and got asked to join their touring group. On top of that, I was promised a seven-book contract for my science fiction/fantasy series, Triorion, by the managing editor of my favorite publishing house. For the first time in my literary career, after years of frustration and despair, I had hope. And hope can be a dangerous thing.

In February, I attended Superstars Writing Seminars. Being a frugal person, I balked at the ticket price, but after the first hour, I realized it wasn’t an expense, but an investment. In that conference room were some very big names in the industry as well as up-and-coming authors, and talking to them without the craze of a Comic Con or being under the stress of selling books allowed us the time to trade secrets, and give each other insight into our publishing experiences. Finally, after years of feeling alone in my literary struggles, I felt like I had allies.

Things started to unravel not too long after Superstars. The seven-book contract fell through, and the touring group disbanded. My mentor, someone who I had deeply trusted, disappeared, leaving me stranded in a strange author limbo. Because of this, I felt plagued by disappointment and frustration, and full of doubt. Triorion was the most important story I had every written, and landing a publishing contract for that series was my greatest wish. Having hope like that—feeling like the publishing contract was right in front of me, only to have it evaporate—left me shattered.

I vowed to never hope again.

In the early spring, one of my good friends called me up and asked me to critique the short story he wanted to enter for the Superstars anthology, Dragon Writers. When he found out I didn’t have a story to enter, he gave me some much-needed encouragement. Still, I didn’t feel like I had much to offer. I was experiencing manuscript burnout from working around the clock on the Triorion series, and I didn’t like dragons. Seriously. Dragons frightened me; they represented a genre I didn’t feel comfortable writing in, and I feared what I didn’t understand about them.

Still, part of me understood that you shouldn’t pass up opportunities, no matter how intimidating or out-of-reach they may seem. But that didn’t mean I wasn’t terrified with every word I typed out for my story, Heart of the Dragon.

In the month it took the editor to get back to us about our entries, my fear turned into anger. I no longer hoped that Heart of the Dragon would be accepted; I knew it wasn’t, and I was all the more frustrated with myself, the writing industry, and all the blood, sweat, and tears I had put into my stories. Triorion fan letters dulled some of the hurt, but I felt beaten down.

And yet, I didn’t stop writing. I can’t tell you exactly what keeps me going. Encouragement from fans is fantastic, as is that ineffable feeling when a character truly comes to life on paper. But there’s something else. Perhaps it’s a mix of insanity and unrelenting desire, but even before I heard back about Heart of the Dragon, I made a decision: I wouldn’t stop, ever. There is no other choice. Writing is a need of my soul.

Now, keep in mind I had vowed off hope and prepared myself for rejection for Heart of the Dragon, but when I opened the email from the editor, and I didn’t see the words, “we regret that we will have to pass,” and instead, “congratulations,” I screamed. Finally, something real—and it was born from my lowest point.

But my biggest challenge was yet to come. Despite a successful convention year, I finally acknowledged something I had been down-playing: I needed to write something other than Triorion. It sold well, but it wasn’t catching fire like it needed to if it was going to get picked up by a big publishing house.

The truth about killed me. After all, I had already written book five, and was well into book six of the seven-book series. How could I stop now? Even with my meticulous notetaking, I was bound to forget some nuance, some critical component of the nearly million-word saga—and I left my characters right in the middle of a terrible intergalactic battle!

As I struggled with my decision, my editor gave me feedback on a short story I had written for another anthology. Along the top of the paper, she wrote in big bold letters: “murder your darlings.” A google search later, and I realized what she meant: I had to kill what I felt was brilliant and precious in my work if I wanted to be successful. I found that it didn’t just apply to that story, but to my biggest decision this year. I had to put aside Triorion.

Inspired by my friends and martial arts training partners, I sat down and wrote, Shadowless: Outlier, the first book in an illustrated novel series. I thought it would be difficult to write something new, especially since I had been writing in the original Triorion storyline for twenty-nine years. However, my 10,000+ hours of writing experience really smoothed out the process, and I ended up writing the entire novel in less than five months.

My year was tough, but in the end, I met a lot of cool authors, sold out at every convention, got published, wrote a new novel, and landed a literary agent. If I could go back and give myself advice about how to manage through the toughest times, I would tell myself this: Stay flexible, say yes to as many opportunities as you can, and get everything in writing.

And it’s okay to hope.

Author L.J Hachmeister writes and fights—though she tries to avoid doing them at the same time. The WEKAF world champion stick-fighter is best known in the literary world for her epic science fiction series, Triorion, and her equally epic love of sweets. Connect with her at: www.triorion.com

Leveraging your IP into a film or miniseries adaptation is one of the best ways to make money as a writer. Not only can you get the income from licensing your rights, but having a major motion picture or miniseries made will give your works access to a much larger audience. The phrase “based on a bestselling series” is good for both sides of the business. It attracts attention to the movie, but it will also give a healthy boost to your book sales leading up to the release.

Leveraging your IP into a film or miniseries adaptation is one of the best ways to make money as a writer. Not only can you get the income from licensing your rights, but having a major motion picture or miniseries made will give your works access to a much larger audience. The phrase “based on a bestselling series” is good for both sides of the business. It attracts attention to the movie, but it will also give a healthy boost to your book sales leading up to the release. However, film has significant advantages in its ability to employ complex visual elements. As authors, we rely on the power of our language to inspire our audience’s imaginations. Film, on the other hand, relies on the skill of the special effects, costuming, and set design teams as well as the training of the actors. When you write a book, be sure to feed those teams with strong, iconic visuals. Furthermore, a five second panning shot can show the thousands of tiny details that would take an author five pages to describe. You get the same effect without having to worry about slowing down pacing.

However, film has significant advantages in its ability to employ complex visual elements. As authors, we rely on the power of our language to inspire our audience’s imaginations. Film, on the other hand, relies on the skill of the special effects, costuming, and set design teams as well as the training of the actors. When you write a book, be sure to feed those teams with strong, iconic visuals. Furthermore, a five second panning shot can show the thousands of tiny details that would take an author five pages to describe. You get the same effect without having to worry about slowing down pacing. Though many of Dresden’s spells were fantastic, they were also remarkably low budget. Making the pentacle necklace glow? Not hard. Blasts of fire would take more skill, but can be done in a number of film editing softwares. As can Bob’s glowing campfire sparks.

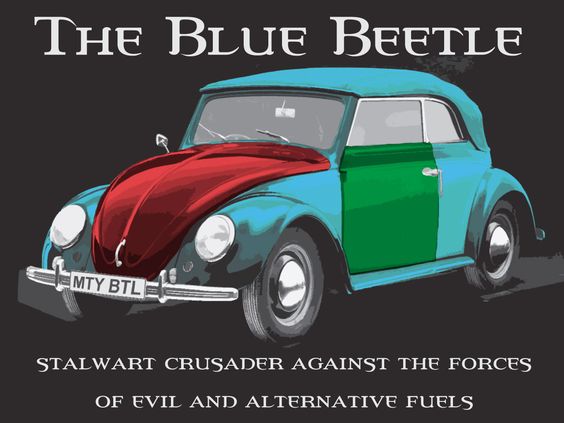

Though many of Dresden’s spells were fantastic, they were also remarkably low budget. Making the pentacle necklace glow? Not hard. Blasts of fire would take more skill, but can be done in a number of film editing softwares. As can Bob’s glowing campfire sparks. For example, the directors of the Dresden Files TV series chose to eliminate the beloved Blue Beetle in favor of a Vietnam era jeep. While the Blue Beetle provided good comic relief in the books, it would have been an extremely difficult set piece to shoot. The director’s camera angles would have been severely limited by how small and enclosed the vehicle was. The only way to get around this problem would be to have multiple Beetles – the first for exterior shots, and a second that was partially disassembled accommodate to the cameras for the interior shots.

For example, the directors of the Dresden Files TV series chose to eliminate the beloved Blue Beetle in favor of a Vietnam era jeep. While the Blue Beetle provided good comic relief in the books, it would have been an extremely difficult set piece to shoot. The director’s camera angles would have been severely limited by how small and enclosed the vehicle was. The only way to get around this problem would be to have multiple Beetles – the first for exterior shots, and a second that was partially disassembled accommodate to the cameras for the interior shots.