A Guest Post by Sonia Orin Lyris

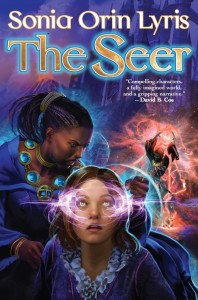

In this month’s theme of work-life-balance, author Sonia Orin Lyris tells us how a real-life encounter with an historian influenced the details in her novel. Sometimes it’s the people we meet in real life who have the most profound influence on our stories. Watch for my interview with Sonia next month on her new novel, The Seer.

Ace Jordyn

***

“I’m a historian”, she said darkly. “I don’t read fantasy novels. They get the details all wrong.”

I don’t typically beg first readers for comments, but this one was special. It was the early days of my world-building on THE SEER and I needed all the help I could get.

I don’t typically beg first readers for comments, but this one was special. It was the early days of my world-building on THE SEER and I needed all the help I could get.

I asked again, very politely, and it’s possible a bit of high-end dark chocolate changed hands. Never underestimate the power of a quality bribe.

World-building trade secret, folks: if you can get a historian to read your story and tell you their pet peeves, every one of them is going to be world-building gold. Whether you make use of their complaints or not, you’ll know something about the why of them, and that’s the path to creating a world that feels real.

I had already done my research, and plenty of it, but no matter how much you study, you’re still responsible for creating the world from scratch, and if it doesn’t hang together right, the reader can feel it. You-the-author are responsible for every detail. Every detail! Consider the world around you, the one in which you’re reading these words. How many millennia did it take to assemble? How many people — in this very moment — are busy making our planet what it is, right now?

A lot. Very, very many.

But to create your book’s world?

Just one. With a little help from first readers, if you’re lucky.

The historian finally agreed. She’d take a look. But she wasn’t making any promises.

I said thank you. (Always be appreciative for the time your advisers give you.) With trepidation, I sent her the first few chapters.

The next week my inbox was filled with indignant treasures, among them this: “No, no, no! This is NOT a D&D game. Coins have names! Coins have histories!”

I instantly knew how right she was. Knew it like the contents of my own pocket.

Pennies. Nickels. Dimes. Not “coppers.” Not “large silvers.”

I dove back into my research and emerged soaked in currency-related facts, from minting to metals, from Greece to China. The facts went on and on, as did the likeness of people and horses and birds and insects, of ships and buildings, of angels and flowers, of myths and monarchs.

So many coins, each symbolizing their culture’s prosperity and priorities. Its very self-image.

I now understood that not only did coins have names and histories, but they were keys to wealth and power, to trade and politics. Coins affected everyone, from rulers to merchants to the poorest of the poor. Coins mattered, and mattered quite a bit.

Coins had names and histories. They had faces. Coins traveled.

That’s when it hit me: Coins are stories.

I felt chills.

Armed with this new insight, along with an overview of thousands of years of currency history, I went back into my world’s empire and made money, and a lot of it. I emerged with sketches of coins and knew what I could buy with each one. I could feel in my hand the weight of the coins and hear the sound they’d make clinking together. I understood how each had come into being, how they were manufactured, and the politics and symbolism behind them.

I already had money in my world, but now I wove it more tightly into the story, and the repercussions of this affected the plotline, and the plotline in turn affected the currency. A circle, much like the coins themselves.

When I came out the other side, my story and its setting had a new shine and hard solidity that had not been there before.

I can tell you, for example, that the most common imperial coin of the Arunkel empire can be broken into quarters, and pieced back together like a puzzle, so you can see the picture of the dog, moon, and queen. Not just any queen, either — the Grandmother queen, a powerful monarch. Well-respected. Perhaps a little feared.

I named the queen and the coin after my historian first reader.

When I told her, she seemed pleased. She might even have smiled a little.

Sonia Orin Lyris is the author of The Seer (http://bit.ly/seersaga), a high fantasy novel from Baen Books (http://www.baen.com/). Her published fiction includes fantasy, science fiction, horror, mainstream, and more, and may be found at lyris.org/fiction . Follow her on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/authorlyris/) or Twitter (https://twitter.com/slyris). You can also read her blog at Noise and Signal.

Evan Braun is an author and editor who has been writing books for more than ten years. He is the author of The Watchers Chronicle, a completed trilogy. In addition to writing both hard and soft science fiction, he is the managing editor of The Niverville Citizen. He lives in Niverville, Manitoba.

Evan Braun is an author and editor who has been writing books for more than ten years. He is the author of The Watchers Chronicle, a completed trilogy. In addition to writing both hard and soft science fiction, he is the managing editor of The Niverville Citizen. He lives in Niverville, Manitoba.