Guest post by Lauryn Christopher

I am a fan of short fiction. Most of the books on my nightstand are short-story collections, and I enjoy dashing off a short story whenever I can. There are many reasons for this, but for now I’d like to talk about short stories that connect to the larger world of an author’s novels, from the perspectives of a reader, a writer, and a businessperson.

As a reader, a short story is a great way to test the waters and see if I like a new-to-me writer’s work without the commitment of reading a full novel – and when that short story is set in the same world as the author’s longer world, so much the better. It’s like going to the store when they’re handing out free samples, knowing that if you like the little taste, you’re more likely to purchase the full-sized product.

As a writer, of all the things I like about writing short stories (which includes challenging myself, and using short stories to help me practice particular writing skills), I think my favorite is the opportunity they give me to wander the side-streets of a larger work. In a short story, I can:

- get to know a secondary character in greater depth

- explore a story idea that doesn’t require the complexity of a novel

- explore an idea or character to see if it’s a world I want to play in at greater length

As an example, my short story, With Friends Like These (at 9,500 words/~40 pages) was written as the result of an intensive writing workshop assignment. But as I got to know the main character, she let me know in no uncertain terms that she had many more stories for me to tell, and I quickly went on to write the novel Conflict of Interest. And thus my “Hit Lady for Hire” series was born.

As a businessperson, I routinely look at each short story in my inventory to see how I can best leverage it. That’s not to say that I don’t go all creative-artist during the writing process – I do, even when writing on demand for a particular market or to a specific theme – but when the story is complete, and the act of artistic creation is finished, I now have a new piece of inventory, and it’s time to put on the business hat.

It’s a simple truth that every additional piece of inventory we create provides readers with one more point of contact for finding our work. Because discoverability is such a critical part of a successful writing career, one way to think of your short stories is like the magic breadcrumbs that lead your readers to the rest of your work. Remember my “As a reader” comment at the beginning of this article – the more of those “samples” you have out there, the more opportunities you create for readers to find you.

Selling your short fiction in to the magazine and anthology markets is another way of leveraging your short stories. Be aware: There are a lot of unpaid markets out there for short fiction, and rates in short fiction markets are typically in the pennies-per-word range, so writing short stories probably isn’t your best plan if you’re looking to get rich quick. However, because short fiction markets only hold onto the rights for a very limited time, when those rights revert, you can then sell reprint rights, put the short story up as an ebook at low or no-cost as a loss-leader, offer it as an audiobook, etc., and continue earning from it. The more you learn about ways to license your intellectual property rights, the more you can put your short fiction inventory to work for you.

It’s often been said that the best publicity for your book is your next book. Well, you can also leverage your short stories as advertising for your related novels. Whenever you sell a short story into a magazine or anthology, in many ways, it’s as if they are paying you to put a multi-page advertisement in their publication and then sending your advertisement (in the form of your short story) to their subscribers – and unless you’re exceptionally well-known, it’s likely that they have a much more extensive mailing list than you do. That short story publication helps you:

- build name-recognition among readers

- keep your name visible between related novels

- give your new readers an introduction to your work and world

- build a collection you can eventually sell/self-publish to accompany your full-length novels

- gives you a “backlist” you can draw from (your previously published short stories). This is a great source of bonus, series-related material you can give to readers when they sign up for your mailing list!

As an example, working around the demands of everyday life (read: the day job), means my readers have to wait a while for the next book in my “Hit Lady for Hire” series of suspense novels. But rather than keep fans of the first book twiddling their thumbs and risk having them forget about me, I released Backstage Pass (at 8,000 words/~35 pages) in a mystery collection, and not only connected with my own readers, but also with the readers of all of the other authors in the collection.

In summary, short stories connected to the worlds of your full-length novels can be great workhorses:

- They keep existing readers happy

- They introduce new readers to your series

- They help you expand your fictional worlds

- They provide an additional income-stream

- They keep your readers happy (it bears repeating!)

If you enjoy reading short stories, there’s a wealth of material out there for you to enjoy. And if you enjoy writing short stories, there’s plenty of readers waiting to read them.

– Lauryn

Lauryn Christopher has written marketing and technical material for the computer industry for too many years to admit. In her spare time, she writes mysteries, often from the criminal’s point of view – they’re not always who (or what) you might expect! You can find information and links to more of her work, and sign up for her newsletter at http://www.laurynchristopher.com

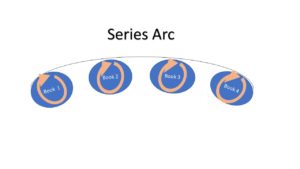

I speak to beginning writers all the time about crafting series. And, after leading off with the whole complete story deal above, I break out the Inception-esque logic of a book-within a book-within a book. Because, really, that’s what we’re writing. The story arc is our overall plot and each book can be seen as an act within the epic structure.

I speak to beginning writers all the time about crafting series. And, after leading off with the whole complete story deal above, I break out the Inception-esque logic of a book-within a book-within a book. Because, really, that’s what we’re writing. The story arc is our overall plot and each book can be seen as an act within the epic structure.