One potentially powerful and useful tool to have in your toolbox is the ability to write in a certain vernacular that makes your characters memorable. Stylistic voicing has been successfully used by some great authors. Let’s take a look at those, and why they were successful.

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

One of the most memorable characters I can think of is Holden Caulfield. The Catcher in the Rye is a staple for coming-of-age readers. It’s my favorite book, in fact. Why? Why did this book resonate with me so much? No, it’s not because I’m

a sociopath, as many critical readers think of Holden. I loved the book because it was real.

We understand that this is the first time Holden has ever truly spoken his mind, consequences be damned. And we get a front row seat! His raw vernacular often includes calling people “phonies” and using “goddamn” as a consistent adjective. This usage of stylistic voicing achieved a certain authenticity. Whether Holden was right or wrong about the other characters being phonies, we never question for a minute that Holden is completely convinced that they are.

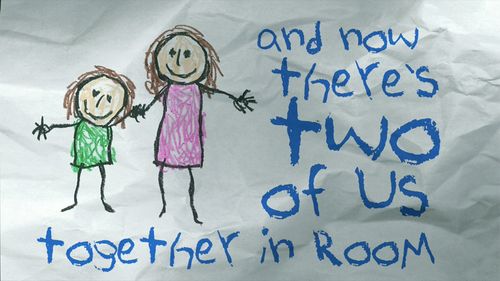

Room by Emma Donoghue

The book Room is told by a 5-year-old boy, Jack, whose main education is the television. Why? Because he is a captive, along with his mother, locked in a shed for years. Jack’s stylistic voicing is so convincing, so well constructed, that the reader is completely enveloped into Jack’s world, where he has only known the  Room. He has never been outside. He hasn’t received any sort of education, apart from the one his mother tries to give him, which makes his sentence construction short and plain. He only describes what he sees, not knowing exactly what certain things mean. But you, the reader, know exactly what it means. And it makes your stomach churn and your heart ache.

Room. He has never been outside. He hasn’t received any sort of education, apart from the one his mother tries to give him, which makes his sentence construction short and plain. He only describes what he sees, not knowing exactly what certain things mean. But you, the reader, know exactly what it means. And it makes your stomach churn and your heart ache.

You may want to pick up Room to see an excellent example of emotional transport with a stylistic narrative voice. It should also be noted that some readers simply could not get past the stylistic voicing. That is one of the risks you take when choosing a stylistic narration, but the rewards can be BIG. Room won Emma Donoghue over ten prestigious awards for her effort and risk.

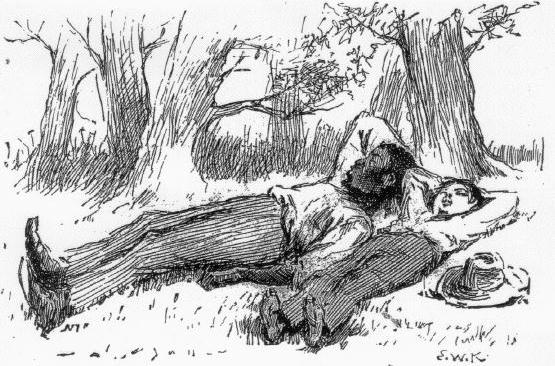

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

Perhaps the most well-known example of using stylistic voice is Huck Finn. It was, in fact, the very first novel published to use American vernacular, or more specifically, regional dialect (an example:“Sometimes you gwyne to git hurt, en sometimes you gwyne to git sick; but every time you’s gwyne to git well agin.”). Huck is described as a pariah, son of the town drunk, and the other children wish they dared to be like him. That’s one hellova introduction. If Samuel Clemens decided to write The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in third person, I venture to say everyone would hate Huck. A bratty little kid, running around  causing havoc. What Twain did so brilliantly was deciding to tell the story from Huck’s perspective, showing us the charm and charisma Huck has to offer, so we can’t help but love the little shit. Using stylistic voicing, Twain made us relate to an otherwise potentially annoying character.

causing havoc. What Twain did so brilliantly was deciding to tell the story from Huck’s perspective, showing us the charm and charisma Huck has to offer, so we can’t help but love the little shit. Using stylistic voicing, Twain made us relate to an otherwise potentially annoying character.

You may have noticed that I chose all first-person novels, as well as young narrators. Can you think of any examples of stylistic voice using adults, told in third person? Was it as effective as a first-person stylistic voice?

If you’re on the edge about whether or not to write a character’s unique voicing, take heart. Mark Twain had never seen it before, but did it anyway. Emma Donoghue received some unkind reviews of Room because of her style choice, and probably cries about it in front of her wall full of awards. Just kidding. She doesn’t. And Holden Caulfield wouldn’t be one of the most notorious voices in literature if Salinger hadn’t let him. Tell your character’s story in the most authentic way possible, even if that includes letting him or her speak for him/herself.