A guest post by DAVID HEYMAN.

2014 for me was a year of education. As I made the decision to move my writing out of the realm of hobby and move towards publication, I immersed myself in every book, course and workshop I could find.

An immediate focus for me was on my characters, as I felt that my initial takes on characters tended to be a bit drab, especially on the protagonists. I wanted my readers to like my characters, to care about them and root for them. One lesson I heard articulated often was something David Farland referred to in his workshop as “petting the dog.” In effect, show your character being nice to someone and people will naturally start to invest in their trials and goals themselves. People like nice people.

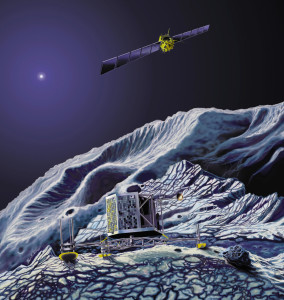

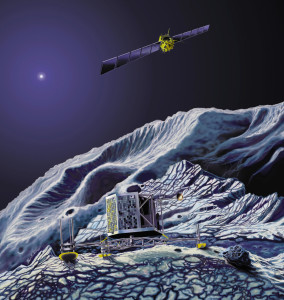

I began to look for examples of this in media, and once I knew to look for it I found it pretty easy to spot. While it was often fairly obvious in television shows, movies and novels, my favorite example of it was not in the realm of fiction at all. It was, instead, in the Twitter feeds of the two ESA probes investigating the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

I began to look for examples of this in media, and once I knew to look for it I found it pretty easy to spot. While it was often fairly obvious in television shows, movies and novels, my favorite example of it was not in the realm of fiction at all. It was, instead, in the Twitter feeds of the two ESA probes investigating the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko.

The investigation of the comet was fairly well captured by the standard media. If you followed the approach and landing on the television news or via news websites, you were given an accounting that was factual, if a bit dry. If you followed the ESA Twitter feed however, you were given an emotional epic. Through the use of nothing more than 140 characters at a time, the ESA wove a story that made its readers care.

The ESA started by anthromorphizing the probes, allowing them to speak on their feeds in the first person. I felt this was a good first step, and one that plays on human nature. As people we seem to be drawn to this model easily, as we go about our lives ascribing emotions and whole personalities to our cars, our favorite shoes and so on. By making the probes speak for themselves, they started to become characters.

Making something a character is not that hard in the perfunctory sense. The trick I have been studying is how to make them likable, and in this I feel the ESA engineers gave a clinic, as these two probes quickly became characters I was invested in. The trick was not in simply letting them speak, but rather what made me care about Philae and Rosetta is that they clearly cared about each other.

Consider the following message orbiter Rosetta sent lander Philae, just after the small probe had separated from the larger lander:

@ESA_Rosetta: Also now back in contact with @philae2014! Good to hear you again buddy 🙂

The probe responds back:

@Philae2014: Nice to talk to you again, @ESA_Rosetta!

The two went back and forth like this, with Philae sending Rosetta pictures of itself and promising postcards from the comet’s surface. They would comment and compliment each other as they went about the work of the landing. When Philae finally completed its historic landing, it was with Rosetta cheering it on by re-tweeting the probe’s landing announcement:

@ESA_Rosetta: Well done my friend! RT @Philae2014: Touchdown! My new address: 67P!

Unfortunately, things did not go as planned for the mission. For a time, the ESA scientists could not locate Philae’s position on the comet. During this period the two probes exchanged humorous messages about the situation, like actual humans would, both trying to keep each other calm in the crisis:

@Philae2014: I’m in the shadow of a cliff on #67P. Where exactly? That’s what my team is in the process of finding out!

@ESA_Rosetta: @Philae2014 you’re in a shadow? How am I supposed to spot you there?! Our teams working hard to find you 🙂

In time it was determined that Philae had bounced on landing, and was now located in an area with much more shadow than expected. Due to this, the solar batteries would not receive the expected charge and soon communications with the probe would be lost.

By this time, my wife and I were fully invested readers. Philae and Rosetta were no longer pieces of machinery, they were now characters we had grown to care about. Through the skillful use of 140 characters at a time, the ESA engineers had made these two matter to us on an emotional level. The writer in me was curious to see how they would handle this new dire situation Philae was in.

I was proud to see they recognized the path the story needed to take. If Philae was going to die, he was going to die a hero. His last tweets were brave, talking about the work he would do until the end:

@Philae2014: I will use all my remaining energy to “communicate” between @ESA_Rosetta and myself with @ConsertRosetta

@Philae2014: @ESA_Rosetta I’m feeling a bit tired, did you get all my data? I might take a nap…

This culminated with a final exchange, where you can almost see Rosetta kneeling by Philae’s bed, telling his young charge that it will be all right:

@ESA_Rosetta: S’ok Philae, I’ve got it from here for now. Rest well…

@Philae_2014: My #lifeonacomet has just begun @ESA_Rosetta. I’ll tell you more about my new home, comet #67P soon… zzzzz

My wife and I held back a few tears while reading this. I kept checking Philae’s Twitter feed for several days, but no new updates were forthcoming. Its batteries drained and its mission complete, Philae was at rest.

Long after the comet mission faded from the news, I continued to think about how emotionally invested I had become. I knew very little about the mission before the landing grew close, and I while I had followed similar missions like the Mars landing with great interest, that is all it had been. Interest.

Philae and Rosetta made me feel. That is a powerful reaction, the very goal of my writing, and I suspect a lot of the investment I grew to have in the mission was from how these two characters cared about each other. As I move forward in my own writing, the lessons I learned here will be ones I hope to emulate.

Guest Writer Bio:

David Heyman writes short sci-fi and fantasy and is working on a novel. He works as a director for a networking company.

Dave writes both novels and short stories in the various genres of speculative fiction. His other passions include his family, his job, gaming and reading about mountaineering. Sleep is added to the mix when needed. You can visit him at

Dave writes both novels and short stories in the various genres of speculative fiction. His other passions include his family, his job, gaming and reading about mountaineering. Sleep is added to the mix when needed. You can visit him at