A guest post by James Orrin.

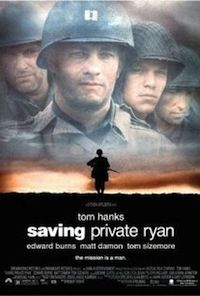

Saving Private Ryan is one of the most acclaimed World War Two films ever made, and also one of my personal favorites. It’s a heart-wrenching story that brings me to the verge of tears every time I watch it.

Saving Private Ryan is one of the most acclaimed World War Two films ever made, and also one of my personal favorites. It’s a heart-wrenching story that brings me to the verge of tears every time I watch it.

I love this movie for many reasons, but especially for what it taught me about fiction – that so long as the story is compelling, the differences between genres are not as severe as we tend to think.

Saving Private Ryan takes place during the Allied invasion of France and centers around a small group of Army Rangers who have been tasked to find Private James Francis Ryan (Matt Damon), whose three older brothers were recently killed in the war. As the sole surviving son of a single mother, Ryan has been given a ticket home. The problem for the Rangers, led by Captain Miller (Tom Hanks), is that Ryan is missing in action somewhere in the chaos of war-torn Normandy. The Rangers will have to sacrifice themselves and their friends in order to send one stranger home to his bereaved mother.

Writer Robert Rodat and director Stephen Spielberg did many things right with Saving Private Ryan. The first was to create a compelling story. It has well-formed characters struggling to maintain their humanity in the midst of war and death. It depicts warfare in its most visceral form: dirty and bloody and filled with moral quandaries. It forces us to ponder tough moral questions, particularly the value of human life and sacrifice.

The first time I saw Saving Private Ryan I was excited simply because it was a big movie about the Second World War. Growing up, I loved to study that period in history and even today I’ll read a book about it from time to time. I find it fascinating because it’s the war most associated with good versus evil – I shudder to think of a world in which Hitler and his allies won the war. But even so, there are examples of greatness and nobility of character on both sides, as well as atrocities. It was a brutal war, fought by humans, each with their own virtues and vices.

However, it took me a while to understand why I like the movie so much. It isn’t based on a true story. There was never a Private Ryan in these circumstances. There was no harrowing mission to rescue one woman’s last surviving son. Even the film’s climactic battle – the battle for control of a bridge in the town of Ramelle – never happened. In fact, Ramelle itself is a fictional town created for the film, and the 2nd SS Panzer Division (the German forces portrayed in the sequence) didn’t join the fighting in France for another month.

You could accuse me of being demanding for noticing these things, but we’re all pretty picky about our likes and dislikes. So how did Spielberg trick me into suspending my disbelief? How did he get me to pretend for nearly three hours that this film really happened?

The key was in the details.

The film opens with a spot-on portrayal of the D-Day landings at Omaha Beach, filled with little details that made me nod my head in approval. From the seasickness that many soldiers experienced on the landing craft as they made their way toward Fortress Europe, to the plastic bags wrapped around the Allies’ weapons to keep them dry during transit, to the types and positions of the German defenses. That first scene was so in-tune with the historical accounts that I found myself in awe of the amount of research it required. But that’s to be expected, right? After all, Army Rangers really did land on Omaha Beach that day… but what about the sections of the movie that never actually happened?

As the movie moved further from historical accuracy, they dropped in little anchor points to ground me to reality, to keep me believing the validity of the events portrayed. None of these anchor points were as large as the D-Day landings. In fact, most of them were small things. One that has always stuck with me is a small comment made during a conversation between Captain Miller and Sergeant Horvath. Captain Miller says about Ryan “He better be worth it. He better go home and cure a disease, or invent a longer-lasting light bulb.” This is a line that’s designed to make the audience feel the main characters’ reluctance to sacrifice their own lives for a faceless stranger, but it’s also more than that.

During WWII, light bulbs were still a pretty big deal, one of those inventions that had changed the world, and it was still a new enough technology that not every home in the United States had them. The light bulbs of the time were also relatively delicate things that didn’t last long. This line served as an anchor to reality in two ways: it showed an historical fact of the time (world building) and it made Captain John H. Miller feel real. The right details, sprinkled seamlessly throughout the movie, are what make this movie feel real for me, despite its historical inaccuracies. And this is true of any story.

These details usually deal with creating believable characters or vivid settings, and can be as simple as an offhand comment or as large as an entire battle. They are things that not everyone will notice. In fact, it’s better if they don’t draw too much attention to themselves – the details should never overshadow the story unless you’re only writing for the enthusiasts. They are there to trick the reader’s mind into believing, if only for a short time, that the events of the story are real.

Choosing the right details may seem daunting, especially if you’re creating your own worlds. But it’s simply a matter of doing the right kind of research. The world has seen a lot of history. Use it as a tool to allow your reader – both the casual observer and the enthusiast – to pretend that your characters and your settings actually exist.

Is your story set in a fantasy culture similar to feudal Japan that’s emerging into its own industrial revolution while religious figures call for a crusade? Research those three time periods, and then choose details that will give your story the flavor of reality you’re looking for. If you’ve done it right, and coupled it with relatable characters, even the exacting enthusiasts of feudal Japanese history (or the Crusades, or the Industrial Revolution) will suspend their disbelief to enjoy your story. In fact, those same enthusiasts will connect to your story on a deep level and become free mobile advertisements for your work.

That’s not so very different from writing a story set in the real world, when you stop to think about it. Are you writing a mystery set in 1930’s Saint Louis? Research that time period. Jot down names of significant people alive at the time, major historical events, popular bars, the local jargon of the time period, methods of 1930’s police investigation, etc. A simple, passing comment (such as a wish for a longer-lasting light bulb) may be all you need to strengthen your setting or make a character feel relatable.

So give your reader a compelling story, and then pay attention to the little details that will make that story feel real. With enough of the right details, your reader will follow you down impossible rabbit holes, or to the surface of a far away planet, or into the very midst of the Normandy invasion.

* * *

James Orrin lives in Northern Arizona, surrounded by the Rocky Mountains and the largest Ponderosa Pine stand in the world. He writes science fiction, fantasy, and a blend of both. His personal website is www.jamesorrin.com.