Guest Post by Sarah A. Hoyt

So you’ve written a novel – but do you know in what genre?

So you’ve written a novel – but do you know in what genre?

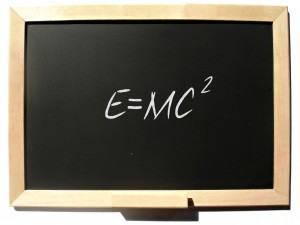

According to Kris Rusch and Dean Wesley Smith, whom I have no reason to doubt, you probably don’t. The reason for this is simple. We writers tend to work from the idea out. If we have – say – this neat idea where you use a machine to perform magic, we go ahead and write it that way. And then we send it out to agents or editors who are likely to run in circles, screaming. (Well, mine did, when I did just that.)

Genre is largely a marketing category. This means that no story fits it exactly. Take the story idea above, and throw in a hot magical engineer and the girl who loves him. Then have her father murdered for trying to market the machine.

Is that novel science fiction, fantasy, mystery or romance?

The answer is “yes.”

In general all novels, no matter how much they are science fiction have a hint of mystery and some romance. (Okay, some novels from the pulp era didn’t.) There is something that must be solved, and someone the character is attracted to.

What used to happen – in the bad old days when your only choice for publication was traditional houses mostly via agents – is that you’d take the book to your agent, and after she ran in circles, screaming, she might tell you “Look, you’re known as a fantasy writer. Knock off with the machine stuff, and emphasize the magic more.” Or “You’re a romance writer, just pump up the romance and wooing scenes and we’ll sell it as a quirky futuristic romance.”

Of course, sometimes they told you they just didn’t know what to do with it. Or they’d tell you what you thought was military SF was actually YA SF, because at the time it was easier to sell as YA and your character was seventeen.

What about now? Well, now it’s all about the tags. One of the things I’ve noticed, when I put up my back list short stories,  is that those I can possibly tag romance (not all shorts have a romance element strong enough to mention!) sell better. But the idea is to tag them or list them with all the genres you think you can get away with. Oh, by all means, tag it for the main idea. For instance, the one above I’d class as fantasy, but then in the description and the tags include the other genres.

is that those I can possibly tag romance (not all shorts have a romance element strong enough to mention!) sell better. But the idea is to tag them or list them with all the genres you think you can get away with. Oh, by all means, tag it for the main idea. For instance, the one above I’d class as fantasy, but then in the description and the tags include the other genres.

As for writing… Well, I tend to write stories as I read them, and I started reading long before I was aware of genres or the idea of genre. I gravitated, mostly, to science fiction and fantasy – but I also read a good bit of mystery because my dad belonged to a mystery book club and it was my sworn duty (I thought) to read every book that came in the house.

I didn’t read Romance until I was in my thirties. Not unless you consider my cousin’s collection of romances, which was in the house and therefore must be read. But those were Portuguese Romances (I was born in Portugal and lived there till 22. My family still lives there. English is my third language, and if you heard me speak you’d believe it. Or maybe not. You’d probably think I was Russian. No I don’t know why. Stop being nosy.) Portuguese Romances all seem to be based on Romeo and Juliet. In the perfect Romance, both die for love, but if you’re very lucky, the girl survives and mourns her boyfriend forever.

Anyway, so by the time I read Romance, I was aware of genre conventions, and how they work, so the book didn’t go against the wall the first time.

See, the thing you have to be aware of, when writing any genre, or tagging the story as a genre, is “genre conventions.”

These are normally invisible to the fan of any given genre, but you do know when they’re violated. They’re simply “the way things are done.” What they do in most cases is get around the awkwardness of telling the story. You know that new machine, in your sf story? You might know how everything works, but you don’t describe it in detail over 40 pages. That’s not the story. You tell us about things it does/is that are relevant to the story. In a Romance, you don’t spend half the book making sure the characters REALLY know one another, before they fall in love. You show instant attraction (usually. Or its polar opposite) and then hints that there’s more in it. In a Mystery, you don’t have the character go “yeah, okay, he’s dead. Big deal. Now, this machine-“ not your main character, at least.

So before you write cross-genre, you need to be aware of what readers of each genre expect. This is best achieved by reading both (all three?) genres you’re crossing, so you’re aware of what the readers expect from each. And hey, once you’re aware of it, you can give the readers special “genre cookies” which will make each of them very happy. For instance, my Darkship Thieves, winner of the Prometheus Award for 2011, has science fiction, romance, and definitely a mystery element. It also happens to be told in the style of Urban Fantasy. The fans of each of these will swear it belongs solely to them. While the Urban Fantasy elements are somewhat mitigated in Darkship Renegades and A Few Good Men, the sequel and not-so-sequel (it’s complicated) it’s still there.

In fact, at this point, I have so many fans from different genres, I have to make sure to put in cookies for all genres every single time.

***

Sarah A. Hoyt has sold over 23 novels and 100 short stories in science fiction, fantasy, mystery, horror and romance. She not only couldn’t confine herself to a single genre, but trying might break her permanently. Her science fiction — the Darkship series and the Earth Revolution sister series — and her Shifter series are published by Baen books. Her mystery, historic mystery, romance, historical fantasy, or whatever she might take in her head to write tomorrow, will be available from Goldport Press or Naked Reader Press (mostly and for now).

Sixteen-year-old me dried off after a long summer evening languishing in the family hot tub with one of my best friends from high school. The discussion that evening had been scintillating. With the tangy scent of chlorine still hugging me like a toxic cloud, I opened the patio door and stepped into the house, my damp feet sinking into the now-soggy carpet. I draped the towel over my shoulders and made my way towards the living room, where my friend was already spread out on the couch. I was pleased he hadn’t gone straight home; true, it was well after midnight, but I was awake. I wanted to converse. I wanted to think!

Sixteen-year-old me dried off after a long summer evening languishing in the family hot tub with one of my best friends from high school. The discussion that evening had been scintillating. With the tangy scent of chlorine still hugging me like a toxic cloud, I opened the patio door and stepped into the house, my damp feet sinking into the now-soggy carpet. I draped the towel over my shoulders and made my way towards the living room, where my friend was already spread out on the couch. I was pleased he hadn’t gone straight home; true, it was well after midnight, but I was awake. I wanted to converse. I wanted to think!