A Guest Post by Brad R. Torgersen

A Guest Post by Brad R. Torgersen

One week ago, I got a call from the President of the Science Fiction Writers of America. He told me that my novelette, “Ray of Light,” was nominated for the SFWA Nebula award — one of Science Fiction and Fantasy literature’s top accolades.

In the week since that phone call I’ve had time to reflect. Being nominated for a Nebula means my story not only connected with readers, it connected with a readership composed of my peers. I’m very gratified and flattered by that, and whether I win the award or it passes to someone else in my category, I can say from now on that my fiction is “Nebula quality,” something I find more than a little astounding when I consider the fact that I didn’t have a single word in professional print prior to 2010.

How did it happen?

Simple: I didn’t quit.

You may or may not have seen this piece of advice floating around: those who can be encouraged to quit writing, should be encouraged to quit.

It’s an old saw, occasionally revived by this or that professional. It comes out of the observation that almost all books and stories that arrive on an editor’s desk — unsolicited — are not up to par. They don’t cut the mustard. They are not professional quality. And the more of this type of manuscript there are, the harder it is to parse out the good stuff. The stories that are worth a publisher’s time. The stories that sell.

There is also a bit of elitism happening, in that many writers — having become authors — want to pull up the ladder behind them. They function from an assumption of finite possibilities. Ergo, there are only so many pieces of pie to go around, and the fewer people jockeying at the table, the less difficult it is to compete for a slice.

I’d like you, as would-be author, to take such admonishment — the urge to quit — with a grain of salt.

Yes, it’s true, not everyone is cut out to be a professional (ergo, paid) writer. There are far, far more people competing for paid publication today than at any time in history, and thanks to the miracle of electronic publishing and cost-friendly on-demand printing, virtually anyone able to string three words together on a page can claim to have been published. Which simply puts the slush pile on display for all to see, whereas it was formerly the editors (and the close associates and family of the unsold writers) who saw such work.

Most of it below the zone. Not photo-ready. You may read some of this fiction on Amazon.com or Barnes & Noble and conclude that the author would have been better advised to take a torch to his computer, than e-publish and put his incompetence on display.

But this is the case for virtually all writers, when they are starting out. And even when they are well advanced into their “learning years,” during which they slog through book after book and story after story with little monetary or professional success to show for it. I know. I spent 17 years in unpublished obscurity, barring a tiny handful of token sales in unpaid venues. I generated somewhere close to 870,000 unpublished words, en route to my first professional-level sale — “professional” being defined according to the SFWA standard of $0.05 US or better, per word.

It’s probable that had a person seen my work at the two year mark, or the four year mark, or even the ten year mark, (s)he might have concluded with confidence: this fellow simply isn’t any good.

Lord knows when I look at my 870,000 unpublished words, I see a lot of stinker manuscripts. Some of them I’ve been able to mine for recent projects: total re-drafting, as new manuscripts which preserve the core characters and/or concepts, while draping these in entirely new prose. Last year I sold two stories which began life as resurrections from the bones of a single, much older story. Which is probably a good lesson in how ideas for stories are plentiful; it’s the execution of those ideas that counts.

Ten years ago I couldn’t execute very well. Ten years ago I was still waist-deep in my “wading pool” practice period. And if I’d had someone come up to me — a real professional whom I admired or esteemed — and he told me I was no good, that I should save my time and trouble, and quit, I might have been persuaded to do it.

Much as it would have killed me inside.

Thankfully, that never happened. I have a spouse who has been married to me literally as long as I’ve wanted to be a professional Science Fiction writer. A few years ago she put her finger in my chest and declared, “You’d better get off your ass and make this thing happen, or you won’t be able to look at yourself in the mirror.” She knew then, as she’s always known, that I was born to do this. That it was in my blood to do it. That even if I tried to quit, I’d unconsciously find excuses to keep doing it any way. In some form or other. And since anything worth doing well, is usually worth doing well enough to get paid for it, the path was clear: shoulder-to-the-wheel, no going back, no turning around, only forward.

Professional, or bust.

Now, some people just think they want to be pros. Having read or enjoyed fiction, or having gotten it into their heads that being an author is a good path to prestige, notoriety, or glamour, they sit down and embark upon the project without realizing that fiction-writing is more like playing a musical instrument, than it is like doing a term paper for school. Good fiction has to be engaging and emotionally transporting in ways term papers or other kinds of non-fiction writing are not. Just as the music we enjoy listening to every day is often several cuts above the barely-passable recital pieces of the technically-able (though passionless) player. Even blog writing isn’t necessarily comparable, because blogs tend to be repositories for stream-of-consciousness expression. Not constructed narrative of the sort that typifies fiction as we know it in the English language of the 21st century.

Most importantly, these people don’t yearn for it in their hearts. It is an aspiration that arises from places not rooted in their souls. Their egoes, perhaps? Or their pocketbooks? But not the very core of their being.

And every once in awhile someone of this type does make it professionally, managing some degree of monetary or critical gain.

But almost always, these people find a reason to put their writing away. And they move on, and are happier for it. Life has prepared them to accomplish other things. And this is absolutely fine. If you find you don’t have the proverbial “fire in the belly” for this work, that’s an important thing to discover and know about yourself, and it’s going to be part of your path to sleuthing out what does inspire and excite you.

But for those writers who discover — often at an early age — that there is almost nothing as satisfying as creating stories, the admonition to quit is a death sentence. Not literally. But a psychic and emotional death.

Many writers who fall into this purgatorial category don’t have the stamina for the long, long haul of the learning curve, but they can’t walk away from writing either, nor can they convince themselves to attempt new ways or new approaches which will help them overcome blockages in their craft. From this pool you can usually draw our critics — people who know something of the art, and may even practice it occasionally, but cannot or will not make the necessary final effort to become totally committed to what is (for me at least) a lifetime vocation.

Don’t be that person. Don’t be the writer who knows deep down in his or her soul that you burn for the stories inside of you, they excite and inflame your spirit like nothing else, but you’re too lazy to put in a 120% effort to overcome your amateur tendencies, fallacies, foibles, and short-sightedness. So you settle into being a sniper against other writers. Or, almost as bad, you become a bitter-ender. Someone who haunts writing forums or conventions and complains endlessly about how the game is rigged, success is about who you know, not how good you are, or that only random, pure luck determines the winners — everyone else gets to be a loser.

That’s horse shit.

The truth: winners across all competitive arenas of popular culture have this one thing in common — they never quit.

You might be deep into a literary adolescence that seems endless. When does it get easier? When do the rejection letters stop? Why aren’t your Kindle and Nook books and stories selling?

You just have to remind yourself of the 10,000 hour rule: it takes roughly 10,000 hours for a person to go from being a raw beginner, to possessing what more or less passes for competence.

Competence in the speculative and fantastic literary field being defined currently as: able to sell regularly to the SFWA-recognized publishers and editors of said field.

At about the 7-year mark in my adolescence, which I date to roughly 1999, I had expended a huge sum of effort and energy on a sizeable raft of short fiction, plus two or three aborted, rather meandering novel projects. I’d racked up a nice wad of rejection slips, a tiny handful with hopeful words on them, usually hand-written from editors: almost made it, or, close but not quite.

I was so frustrated I could taste it. Every day. My youthful idealism about writing had given way to an encroaching cynicism. Was I a permanent second-class citizen in the writing world? How come other people seemed to be leaping out into the vanguard of Science Fiction and Fantasy while I seemed utterly unable to penetrate? Was I a life-time wannabe? What more did I have to do to prove to the editors that I was worthwhile?

Several more years passed. I abandoned short fiction almost entirely, in favor of several newer, more focused novel projects. But here again I hit a wall: the novel (in my estimation) proved an entirely different animal, compared to the short story. It was impossible (for me) to navigate my way from point A to point Z in a book, by the seat of my pants, as I’d been able to do going from point A to point E in a short story.

I also got busy with life. I was still married. I had a full-time civilian career, and a new secondary career in the Army Reserve. I was also a new father. Whatever free time I’d been used to devoting to writing up to that point, vanished in the blink of an eye. No more could I rely on keeping “hobbyist hours,” it was either find a way to write, or the writing wouldn’t happen at all.

So, I did what a lot of writers at that point are prone to do: I lapsed into a state of near-quitting. If not in my heart, then in practice.

At which point my wife rescued me — good spouses are hard to find, but made of solid platinum. I highly recommend getting one.

In 2005 I had to come back to the effort almost like a beginner. Start from scratch. Clear the stable of old stories and ideas and prejudices and concepts and habits. Be bold. Go in new directions. Try things I’d never tried before.

It wasn’t an instant difference. The rejections I was getting in 2006 and 2007 weren’t any different from the rejections of 1996 or 1997.

But I was a different person. I was older. I’d lived more life. I’d had some scales fall from my eyes, and I’d been humbled by many setbacks. I’d seen some tough times and ridden out a few very rough spots. I’d learned the value of dogged, stubborn persistence in the face of almost overwhelming obstacles, thanks to my military experience. And I’d learned a thing or two about how people truly work, inside, thanks to my marriage, and raising a child. Both of which required me to subsume or subjugate my ego for the sake of more important things.

In 2009, it finally happened. Writers of the Future called to inform me that my story, “Exanastasis,” had won placement in the third quarter of the 26th annual installment of that anthology. 60 days later, Stanley Schmidt — editor of Analog Science Fiction and Fact magazine — wrote to inform me that my story, “Outbound,” was being purchased for publication. A double-win, considering that both stories had been focused efforts to secure a spot with Writers of the Future. “Outbound,” has since gone on to do wonderful things for me via re-sales and gathering the attention of Hollywood people, a top agent in New York, as well as a readers’ choice award. While the Writers of the Future Contest exposed me to a troupe of highly-successful professionals, some of whom — like Mike Resnick — have gone on to become important mentors, as well as good friends.

And that was just the start. Stanley Schmidt wasn’t the only editor buying. Other editors liked me too. Or at least, they liked my stories. Suddenly there was real money flowing into the family budget. Thousands of dollars! And success began to build upon success, sale upon sale, until I’d managed to grab the attention of a major novel publisher too, thus positioning myself to make the crucial (in my mind) expansion into that lucrative arena.

Now, the runway lights are lit — I just have to land the airplane!

An thus comes the call, for the Nebula nomination.

Oh wow.

Could I have planned on it? No. In fact, I would highly advise you to keep awards like the Nebula off your bucket lists, because the Nebula is a voted award (not blind, in the manner of Writers of the Future) and you could be a very successful, financially-lucrative author and never come close to either a Nebula or a Hugo — the other major award in Science Fiction and Fantasy. These things cannot be won through hard work or effort. Success can be won in this fashion. But the awards are entirely beyond your control.

Which is why it’s a unique surprise to discover that someone has decided to put you in for one. Or that enough someones have put you in to actually get you onto the short list, from which the eventual winners are to be picked.

None of it would be possible, if I’d quit. If I’d looked at myself in 1995 or 2000 or 2005, and concluded, “Nah, it’s a waste of effort, I will never be a writer,” and slammed the closet door shut on my dream. There was every reason to quit at those times. I wasn’t selling a word. I wasn’t making a dime. There were many, many things which were all far more immediately important to myself and my family, on which I could have devoted all of my time. And nobody — save my wife — would have blamed me if I’d been practical, sensible, pragmatic, and tried to stop being a writer. After all, everything up until then indicated I wasn’t any good at writing. That the best choice would be for me to stop wasting my time.

I never made that choice.

I hope you don’t either.

If you’ve got the stones for the project — whether male or female — and if you’ve concluded (either through long experience or perhaps through rare, personal insight) that you simply cannot walk away from it, then you owe it to yourself to keep going. To keep trying. To not give up. To absolutely refuse to fail.

There is far more of my new-found success rooted in persistence and long-suffering, than in talent. There are thousands of far more talented writers in the world. Yet I am the one with the Nebula nomination. And it’s because I didn’t give up or let myself make excuses. Also, my family didn’t let me give up or make excuses. And now I’m seeing the rewards of my labor, and I can state with conviction that there have been few greater or more satisfying experiences in my life, than seeing my stories — my words — reach professional print, and go on to some measure of professional acclaim.

Oh, and the money’s cool too.

Guest Writer Bio:

Brad Torgersen has sold his fiction to

Analog Science Fiction and Fact magazine,

Orson Scott Card’s Intergalactic Medicine Show, and has launched several novelettes on both the Amazon.com Kindle and the Barnes & Noble Nook platforms. He has collaborated with award-winner

Mike Resnick on a short story for Ian Watson’s

The Mammoth Book of SF Wars anthology, due out in 2012, and they are currently collaborating on a second military SF piece for a different anthology. He also has serial collaborations in the works with old friends from the

Searcher & Stallion graphic audio drama. His novelette, “Outbound,” won the

Analog “AnLab’ Readers’ Choice award for Best Novelette of 2010, and his novelette, “Exanastasis,” won the

L. Ron Hubbard Writers of the Future award, appearing in the Contest’s 26th volume. You can read more from Brad at

http://bradrtorgersen.wordpress.com/.

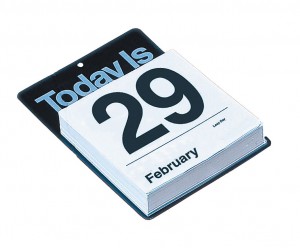

It always baffles me that more people don’t get excited about Leap Day. It’s not a holiday. In fact, this year it’s just a typical Wednesday. The morning shows might make some casual reference to the calendar oddity, but apart from that it will go largely unremarked upon by the world at large. A much bigger deal will be made of Groundhog Day, which is pretty mind-blowing when you stop to think about it. (Yes, I’ll say it: Groundhog Day is ridiculous.)

It always baffles me that more people don’t get excited about Leap Day. It’s not a holiday. In fact, this year it’s just a typical Wednesday. The morning shows might make some casual reference to the calendar oddity, but apart from that it will go largely unremarked upon by the world at large. A much bigger deal will be made of Groundhog Day, which is pretty mind-blowing when you stop to think about it. (Yes, I’ll say it: Groundhog Day is ridiculous.)