A guest post by Ramón Terrell

The resident dictionary in my computer defines setting as “the place in time in which a play, novel, or film is represented as happening. As is its job, the ole dictionary gives you a sterile definition of something much more … alive.

A novel’s setting is its history, its present, and its future. It is the body inside which the story lives. Without it, you just have characters in a vacuum. I’m reminded of the time I took a mocap (short for motion capture) class. After I slinked into the skintight black mocap suit, and they fitted me with all the little white dots, I moved into the center of the circular space to go through the motions.

There was a giant screen on the far wall that displayed my movements in the form of all the dots on my body. For the purposes of this post, I’ll gloss over my elation at imitating Ken and Ryu movments from Street Fighter, or Scorpion and Sub Zero from Mortal Kombat. Or even Eddie Gordo from Tekken. While those moments were a fun and laughter-inducing reliving of childhood/young adulthood, the memory of this adds a layer to this subject. The character in a vacuum.

While I was busy playing characters onscreen, the guys on the computer were creating a troll to inhabit the white dots that I provided. Soon we had a big hulking troll monster on screen, and I was its brain. Now, while seeing the guys behind the computer screen work their magic so quickly was cool, and me making the thing move even cooler, it sat on a screen, by itself, in a vacuum. The truth is, they could have gone on to inhabit that screen with thirty more trolls, included a giant, or even a dragon. But at the end of the day, they would all have been really cool figures in a vacuum devoid of any life but themselves.

Setting, is not just the location a story takes place. It’s not just a mass of buildings, mountains, lakes, flowers and trees. It’s a character in the story, whether background or lead. In The Lord of the Rings, Middle Earth was very much a main character of that series. The sense of vastness and wonder of the place, the mines of Moria, the forests home to powerful sprites such as Tom Bombadil, the lush green homes of the Ents, on their endless search for the Ent Wives, who probably left because they were tired of picking up after their Ent husbands. The darkness and evil of Kazaad Dum. It goes on and on.

The setting is everything that a character loves or hates about their lives, their situation, their past, the anxiety of their future. It is that place of danger and deviousness that the protagonist has been told to avoid, yet dreads the inevitability of her having to go. Throughout her journey to this horrible land, the protagonist is filled with worry about what she will find there. She mentally and even physically prepares herself for the sly, conniving men, the whip-like wit of the women, and the defiant children she will encounter. She hones her senses, wary of the packs of feral dogs roving the city borders, the twisted and gnarled trees reaching their clawed branches over the trail to snatch up foolish travelers passing through the dark night. She thinks of the black buildings, sitting prostrate before the giant black tower glaring down on them.

But when our protagonist reaches what her friends have described as this place of unending darkness and despair, she discovers a city with buildings dark of color that appear black at night, but are quite beautifully designed homes, pavilions, tailor shops, bakeries. The old gnarled trees are actually thousands of years old, and she can feel the silent wisdom of many ages past wafting from the regal figures. Packs of dogs do indeed rove the city limits, chasing off bears, making wolves think twice about venturing too close to the meadow where families like to picnic. The families bring extra food that they happily share with their canine protectors.

The men of the city are excellent at a game called Spy’s Eye, in which their team uses treachery and deceit to win over their opponents. It is such a beloved game that they playfully prank each other in daily life. Women have a whip-like wit that is seemingly present at birth, since the society is matriarchal, and women hold the most powerful positions of politics.

Children are trained from a young age to be strong of mind, for the world is dangerous outside the borders of their home, and one never knows what or whom they will encounter during their travels.

Our protagonist is instantly overwhelmed at the sight of the dark-colored buildings downhill from the huge tower that provides a breathtaking view of the surrounding land. It is a tower of observation that all may enjoy. Climbing the steps of the tower is a tiresome affair that not many will complete, yet those who do reach the top are afforded the perspective of a view of a world much bigger than they are; a reward for the labor of achieving it.

In these two examples, we have a setting built in the imagination of our protagonist based on rumors from her childhood. Her friends may have ventured to this place when very young, been frightened by the trees, the large buildings, the people who might have been very different from those from the land of their birth. This setting is stays with us and the protagonist all the way to her destination. Then we see that this is actually only partially true, and that with her own eyes, the protagonist sees the buildings, the trees, the dogs, the people, for what they really are.

Our setting has changed.

In any given story, we will more often than not have multiple settings. Even if it takes place in only one city throughout the entire story, there will be more than one. Our characters will venture from the slums of their home, to high society once they’ve attained a job. They may perhaps earn enough money to move from the slums to middle society where they will own a home in a nice community.

One day a dragon may fly overhead and torch the entire city. Now we have another setting; one of fire, ruin, and death. To stop the dragon, our protagonist may seek the help of a wizard who gives him the ability to breathe underwater, and he ventures deep into the caverns of the ocean to seek help from a water dragon to battle the evil wyrm who destroyed his home. In his journey to the water dragon, we see all manner of sea life.

Why have I illustrated all of this? That’s the fun part. We go to a film, open a book, go to a play, to suspend real life for a while. We wish to be transported into a setting not our own, whether real or fictional. Some readers love political thrillers, while others enjoy flying on the back of a dragon. With either of those genres, a character must be somewhere. Be it in a courtroom, in front of the desk of the Prime Minister of a country he was just caught spying in, or in the lair of a dragon who would love to know why he shoved that one coin into his pocket. A character’s journey cannot happen without a place to journey within. Even in their own mind, there is some kind of setting.

So go forth, lovely readers. Find a setting and dive into it. Pick up a game controller and do things in ancient Egypt, Rome, Japan. Open a book and leap through the treetops over the shoulder of a band of wood nymphs. Settings are as endless as our imaginations, and our abilities to use the built-in virtual reality of our own minds to visualize them. And isn’t that, a truly wondrous and wonderful thing?

About the Author:

Ramón Terrell is an actor and author who instantly fell in love with fantasy the day he opened R. A. Salvatore’s: The Crystal Shard. Years (and many devoured books) later he decided to put pen to paper for his first novel. After a bout with aching carpals, he decided to try the keyboard instead, and the words began to flow.

As an actor, he has appeared in the hit television shows Supernatural, izombie, Arrow, and Minority Report, as well as the hit comedy web series Single and Dating in Vancouver. He also appears as one of Robin Hood’s Merry Men in Once Upon a Time, as well as an Ark Guard on the hit TV show The 100. When not writing, or acting on set, he enjoys reading, video games, hiking, and long walks with his wife around Stanley Park in Vancouver BC.

Connect with him at:

http://rjterrell.com/

R J Terrell on facebook

RJTerrell on twitter

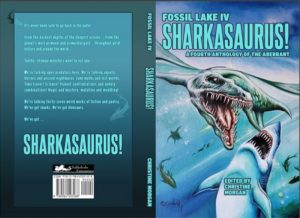

Have you been swimming in Fossil Lake?

Have you been swimming in Fossil Lake?

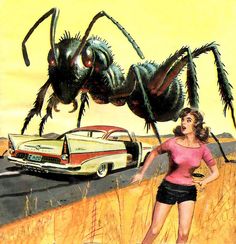

Yes, this is an option. You can set your mutant giant ant story in Nevada, and they all die because they’re allergic to saguaro cactus. The problem with this is saguaros live in the Sonora Desert in Arizona.

Yes, this is an option. You can set your mutant giant ant story in Nevada, and they all die because they’re allergic to saguaro cactus. The problem with this is saguaros live in the Sonora Desert in Arizona. You could always make up an establishment, but make sure you’re vague enough that people can’t say, “Oh, that’s where DiFara’s Pizza is. He’s been there since 1965. Also known as one of the very best places to get a pizza in the galaxy.”

You could always make up an establishment, but make sure you’re vague enough that people can’t say, “Oh, that’s where DiFara’s Pizza is. He’s been there since 1965. Also known as one of the very best places to get a pizza in the galaxy.”