J. R. R. Tolkien famously created entire languages and histories as part of his creation of one of the greatest world building exercises in all of literature. Even that wasn’t enough to satisfy his desire to create a complex and vibrant world. He used those languages to create unique poetry and songs, which he then translated into English as part of putting the Lord of the Rings on paper.

Frank Herbert had reams of notes detailing the history, economies, royal house intrigue and genealogy of a “world” that was far too epic to fit even onto one planet.

Is it necessary to mimic their herculean efforts in order to create immersive, believable worlds for your own story?

No, it’s not. Certainly you don’t need to create entire languages.

But it can be helpful if your readers wonder if you did. And that might be easier than you think.

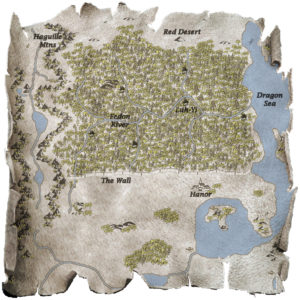

One of the more consistent compliments I get on my War Chronicles novels is on the depth of world-building. I made a determined effort in writing those books to create an epic feel, not just for the character story arcs, but for the entire world. Not just for the story’s time, but for thousands of years into the past. Not just for the physical geography, but for the spirituality and myth.

Sometimes less can be more. In that story we encounter an ancient empire, one that is tied to the current story through a thread that traverses millennia, and will likely continue on into the future. To create the sense of an ancient empire that was palpable and relevant to the story, I wove that empire into the story whenever I could, in the most natural ways I could devise. But I didn’t write a hundred page treatise on that empire, I didn’t create languages.

What I did, was to have the empire be remembered in the land itself. The great mountain range dominating the  main continent is named after that empire. Ancient structures dot the landscape. Terms are woven into the language of the townsfolk, idioms and proper names woven together even through dialog.

main continent is named after that empire. Ancient structures dot the landscape. Terms are woven into the language of the townsfolk, idioms and proper names woven together even through dialog.

The illusion all this brings forward is one of an ancient empire, so powerful that its great works of art, science and architecture are still the pinnacle of culture and technology. Bridges and temples not only still exist, but some are still maintained and revered by their descendants.

The same approach works for geography and biology. A little variety, consistently applied, can create a compelling sense of distance and scope. As your characters move through the world, change the details of the local flora, fauna and terrain. New sights, sounds, even smells can delight or disgust your characters, which flows through their eyes and into the minds of your readers. Smell, in particular, is a very powerful memory aid. If you can associate a place in your book to a smell the reader recognizes and has a strong emotional response to, you can almost guarantee that place will stand out in their mind as they read it.

Finally, one of the most powerful ways to give a sense of world-ness to your story is to weave these different techniques together. Flowers can be associated with ancient rituals. Tolkien almost literally wove his history into his scenery. Think of the Dead Marshes, The Old Forest, Fangorn forest, Lothlorian… each place unique, each place memorable, each place as much a part of the myth and folklore as it is a part of the physical geography.

Once you start thinking about the story this way, opportunities to use these techniques will appear as you write, or as you edit.

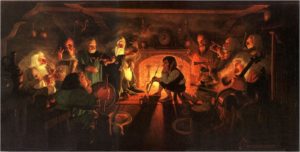

At this point we see Bilbo sitting outside smoking some pipe-weed. This is the kind of small detail that can transform a scene and make it rich and lively. He is enjoying his morning when Gandalf wanders by. Again, the small details about Gandalf’s background are sprinkled generously to immediately capture the attention of the reader, and it’s masterfully done. We want to know more about this wizard and the adventures he’s been on!

At this point we see Bilbo sitting outside smoking some pipe-weed. This is the kind of small detail that can transform a scene and make it rich and lively. He is enjoying his morning when Gandalf wanders by. Again, the small details about Gandalf’s background are sprinkled generously to immediately capture the attention of the reader, and it’s masterfully done. We want to know more about this wizard and the adventures he’s been on! That beginning spot where Bilbo is puffing away and getting a bit annoyed at Gandalf for butting into his quiet morning, only to be dressed down after Gandalf reads Bilbo the riot act “as if Gandalf was selling buttons at his door”, shows a lot of subtle worldbuilding. We learn a bit more about the culture of the hobbits and, at least at first, that this particular hobbit starts off with a cheerful outlook. When the idea of adventures pop up in conversation we discover that hobbits like being predictable, and that there are no adventurers around Hobbiton. The droplets of culture are helping to build out the world of the Shire without being obtrusive. Instead of handing the reader a laundry list of boring and sometimes unnecessary information, Tolkien slips us small doses that we can consume without getting bored.

That beginning spot where Bilbo is puffing away and getting a bit annoyed at Gandalf for butting into his quiet morning, only to be dressed down after Gandalf reads Bilbo the riot act “as if Gandalf was selling buttons at his door”, shows a lot of subtle worldbuilding. We learn a bit more about the culture of the hobbits and, at least at first, that this particular hobbit starts off with a cheerful outlook. When the idea of adventures pop up in conversation we discover that hobbits like being predictable, and that there are no adventurers around Hobbiton. The droplets of culture are helping to build out the world of the Shire without being obtrusive. Instead of handing the reader a laundry list of boring and sometimes unnecessary information, Tolkien slips us small doses that we can consume without getting bored.