When it comes to writing horror a lot of readers and authors assume that the actual horror has to come from something otherworldly — vampires, werewolves, demons, etc. Otherworldly horror is cool but for some readers and authors it’s not something they enjoy. Personally, the second a demon appears in a scene I’m out. So it’s a good thing that horror is a lot more broad and versitile then that.

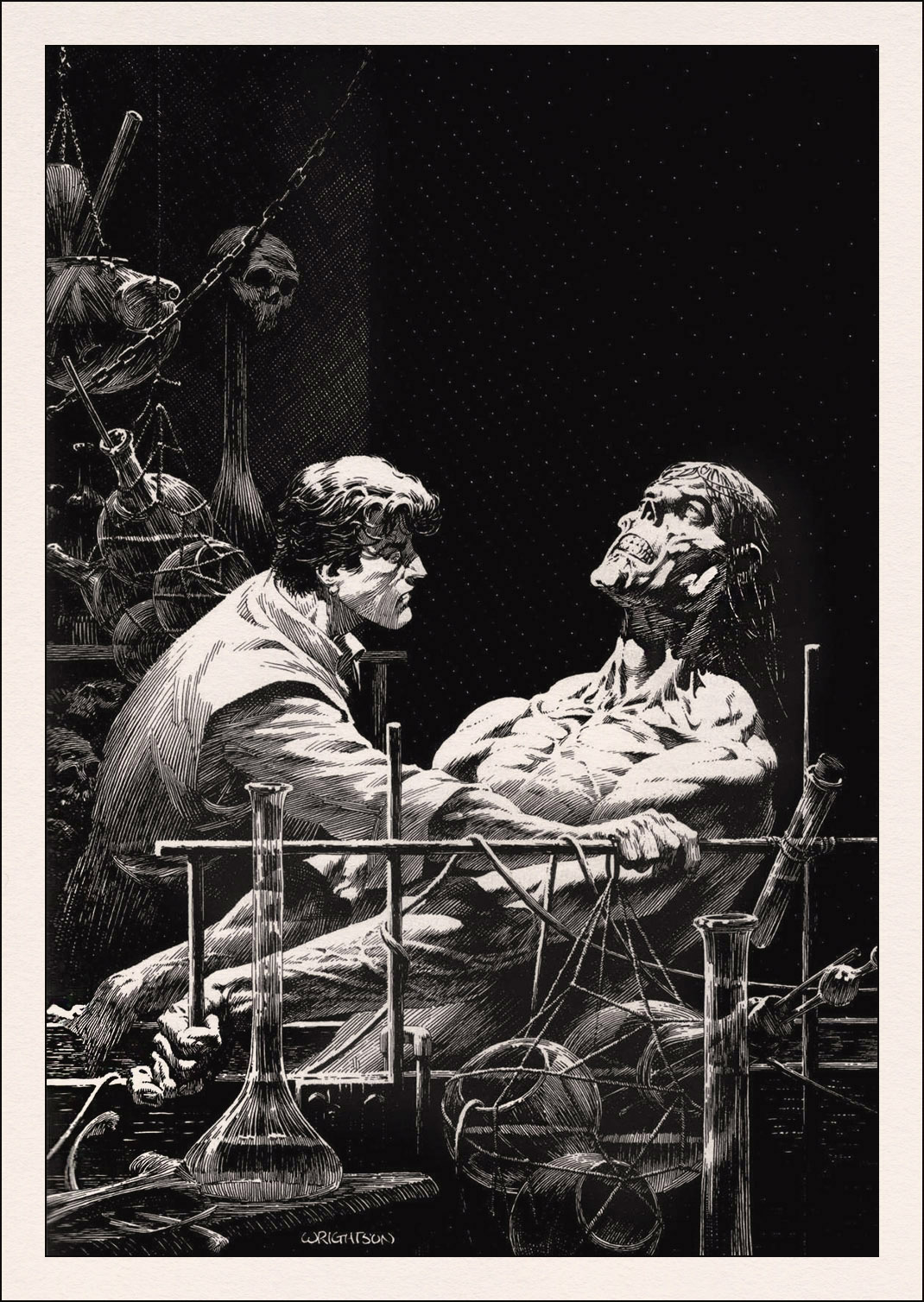

While the otherworldly is terrifying, the everyday is just as scary. In my opinion the otherworldly is scary because it’s the unknown. It’s unknown why they exist, why they want to harm or kill someone, and how powerful they will become if they aren’t stopped. It’ s human nature to fear the unknown which is why this works so well despite the fact that no one is ever going to be accosted by a real Swamp Thing at summer camp.

The whys may be known for the everyday threats (why a person snapped and went on a killing spree, for example) but it’s usually not known until afterward. In the moment it’s still unknown and terrifying. Add to that the fact that these are threats that actually could happen and that multiplies the fear factor. Take Silence of the Lambs. It’s not usually thought of as a horror film but Buffalo Bill and Hannibal are terrifying psychopaths. The scene where Bill’s captive discovers the bloody fingernails of previous victims in the pit? Pure horror.

Not comfortable with something that psychotic? How about this: In Joe Hill’s The Fireman (spoiler alert) the scariest people aren’t those with supernatural abilities. It’s the ordinary humans. High stress situations often bring out the worst in people and Joe highlights that in this book. The actions of the “normal” people are far more horrifying then those affected by the supernatural. Dan Wells does something similar in I Am Not a Serial Killer. In this book Dan pits a teenage sociopath against a demon serial killer. It’s a fascinating contrast! Yes, both of those examples are technically horror novels but I think that they do a marvelous job showing how the supernatural and everyday horrors can be juxtaposed to highlight the other.

How about something far more ordinary. What if your character has Alzheimers? Their memory fades in and out. As the story goes on they know less and less until they have no idea who their caregivers are. They think they’re being held against their will and try to escape but their captors catch them every time. From whichever POV you choose it’s a scary situation. The Alzheimers patient thinks they’ve been abducted while the caregiver is terrified of them getting lost in a nearby wooded area or hit by a car if they get out of the facility/house.

I feel I should mention that this type of horror should be used with care. Because you don’t have the safety of reality to reassure the reader it can linger in the mind. Also depending on the everyday horror that you use it might even overshadow the plot. It’s definitely something to be considered carefully before inserting it into your story. If that’s the exact effect you want, then perfect! But if you’re writing a light romance novel, having the villain go full Hannibal Lector on the heroine might be a bit too much. Plus it’s a good idea to at least hint at these elements being present in the blurb. A lot of real world horrors have real world survivors and the last thing any writer wants do is to unwittingly trigger a reader’s PTSD.

As terrifying as Lovecraftian horrors are, using real world horrors can make your stories far more terrifying. Whether you use a small one or a big one, it’s really useful and effective way to make your story interesting without falling into a trope.