Does a series need an overarching story arc where a question or problem takes several books to resolve? Not all series have an overarching story arc and whether or not you need one largely depends on genre.

Fantasy and science fiction series often have a broader question which needs to be solved or an antagonist who needs to be conquered. Sometimes it is the same antagonist, like Voldemorte in the Harry Potter series, or an antagonist who can change like Larry Brooks’ Shannara Chronicles where after season one in the television series, the antagonist got a new face (but he’s still past of the evil cesspool) and the struggles continue.

Children’s series and crime/mystery or thriller novels don’t need to have an overarching plot problem to be a successful series. Both these genres rely on strong character development and setting to keep the series together. These books stand alone in that they deal with a crime or issue independently and the antagonist or issue is completely resolved. In these series, the character doesn’t need to grow or change, not a lot at any rate. Readers enjoy the characters unique quirks and relationships and they come to rely on their unchanging nature. That is why some series, such as James Bond have lasted for so long. Viewers know what to expect and that’s why they keep coming back.

Crime novels which have stand alone plots can still be tied into a series through their subplots. Such subplots can deal with relationships or fatal flaws such as alcoholism. In these novels, the crime may be solved, but the personal issues are not. Crimes become the setting for character development and the theme of each book speaks to some personal element of the subplot. An excellent example of this is James Runcie’s Grantchester Mystery Series which has been made into a BBC television series in which amateur sleuth and vicar, Sydney Chambers, helps solve a crime. Subplots in the form of personal and local issues resonate in the theme of each episode for main and secondary characters. At the end of each episode, Sydney’s Sunday sermon sums up the theme quire brilliantly.

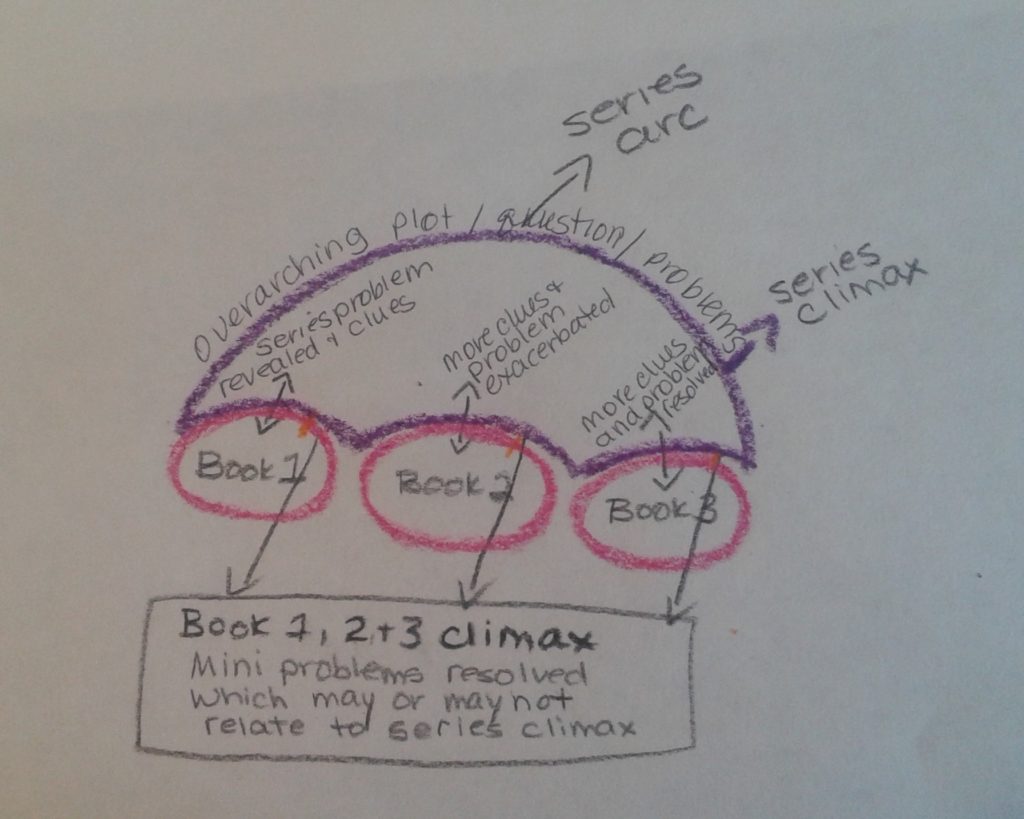

To create a series whether it be fantasy, science fiction or crime and which has an overarching plot or question, it’s best to map out a few things so that series focus and perspective isn’t lost. Even if you’re a pantser, there are a few things to know before you start writing. Writing a series with an overarching plot or question looks like an umbrella.

The unbrella metaphor helps keep the series in perspective and allows me to include things where they’re the most needed. It keeps issues separated, at least for plotting purposes, helps avoid the murky middle issue for the series and helps keep the series plot unresolved until the end. Here are a few tips for planning hte series and book arcs:

- Determine the plot or character problem to be solved by the end of the series. If the protagonist is after a villain, then the climax at the end of the series will be when the two battle it out. If unrequited love creates the resulting climax, know if it will be a happily ever after, an unresolved tragedy, or an acceptance or a moving on with a new person.

- Determine each book’s plot or character problem. Resolve that to a satisfactory conclusion. In a crime novel, the criminal is caught. In a fantasy, the fortress is safe and secure from the evil wizard.

- Develop the setting and determine key elements so they are consistent throughout the novels.

- If your character needs to grow and change, know the degree of this change in each novel. You can’t have the protagonist acting the put together and able to handle things effectively in Book 2 when their great ‘aha! moment’ isn’t supposed to happen until Book 3. If that happens, in Book 2, Book 3 will be redundant.

- Think of each book as an act in the series arc (for example, it could be a three or five arc plot). In a trilogy, Book 1/Act 1 introduced the problem and reveals clues. If it is a fantasy, for example, it may be that this is part 1 of the hero’s tussle with the villain and a resolution of some sort happens. The hero may have won the skirmish for now, but the bigger battle is yet to come. Book 2/Act 2 there are more clues and tension increases (murky middles are not allowed!). The hero tussles with the villain more, stakes increase, losses and wins occur. An unrequited love is so close yet so far – hope is won and lost. Whatever the series problem is, now is the time to keep it interesting and happening. Book 3/Act 3 is the most complex and fun to write. Both the book arc and the series arc are dealt with and concluded. All the clues, ideals, character quirks are resolved. But, keep a series diary so that details ad clues are consistent because if you mess up, your readers will tell you.

- If the book arcs don’t directly relate to the series arc, but support it, make sure the events reflect, at least in a thematic way the series issues. Think of it this way: whatever personal issues the protagonist faces, he will see the world through those lenses. For example, the self-absorbed alcoholic detective struggles for self control on the job. He will observe and understand issues of self control because he can relate to them. Or, the thriller hero. She may be the stereotypical adventurer who has no desire for long lasting relationships and approaches the world with an abject lack of sensitivity when it comes to understanding people on a personal level.

Have fun creating your own series umbrella. As you saw in the diagram, I like crayons and squiggles when brainstorming.

Some final tips:

- Understand the overall gist of what you’d like to write. Know the beginning, the climax and the end result of the series.

- Write Book 1.

- Step back and note the problem and the clues you’ve planted. Ask if this is going in the direction you want and most importantly as if the larger problem is sustainable? Does it have enough traction for the series or can it be easily resolved? This is the time to up the tension, the stakes and the problems to avoid the murky middle novels!

- Revise Book 1 with Book 2 in mind. In fact, I prefer to have even a broad outline. This will help ensure that factors, character traits, clues and setting issues don’t come back to haunt you in subsequent books. I have heard authors complain after Book 1 has been published that they have written themselves into a corner in Book 2 because they can’t change a small detail in Book 1 which greatly affects the plot in Book 2. So, plan and think ahead as much as you can and keep a series diary!

A series can be along and rewarding journey and you must be in love with it in the middle of Book 4 as you were in Book 1. With a little planning, and an eye on the series and individual book arcs, your writing journey will be filled with adventure, personal accomplishment, and the gratitude of loyal readers.