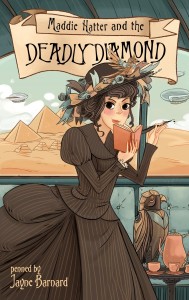

Welcome to my second interview with author Jayne Barnard and her steampunk novel MADDIE HATTER AND THE DEADLY DIAMOND.

In my previous interview with Jayne, Jayne Barnard on Maddie Hatter’s Steampunk Society, we spoke about Maddie’s life as a Steamlord’s daughter, the constraints  and attitudes of the Victorian era and how it affected Maddie’s quest for independence. Jayne’s historical accuracy made this steampunk novel very believable. Even the mechanical gadgets, like Tweedle Dee the mechanical bird who is Maddie’s companion, seem commonplace.

and attitudes of the Victorian era and how it affected Maddie’s quest for independence. Jayne’s historical accuracy made this steampunk novel very believable. Even the mechanical gadgets, like Tweedle Dee the mechanical bird who is Maddie’s companion, seem commonplace.

Today, we’ll learn more about how Jayne chose to create Maddie’s steampunk world, and about Steampunk’s fine sport of dueling with parasols.

Dueling parasols? It’s not in Maddie’s book, but I know you’re personally involved in this sport.

Victorian women’s lives were very much constrained by the clothing they wore and social rules of their class. Even more than in this age of internet slut-shaming, their behavior could be judged without mercy by their peers and, if their families were important, by the tabloid press. Their chances of marriage, the only career open to most of them, were dependent in large part on not attracting public notice. Thus they had to swallow a lot of subtly and overtly insulting behavior from other women who, because of their relative money and social power, did not need to be as well-behaved.

Men could settle combat by dueling with swords or pistols, by fisticuffs (aka boxing), by racing, or any other means they chose. They considered those means honourable, and a man who shirked, or who did not abide by the result, lost his honour. It was an outgrowth of the old trial by combat system. Parasol Dueling, a non-contact combat sport based on ranking parasol moves or ‘figures’, gave Steampunk women a means to settle insults rather than allow them to fester until the women broke out in mean-spirited or socially unacceptable behavior. Parasols allow for non-contact dueling that any two ladies may engage in at any place where a parasol might be carried.

Where can we learn more about dueling parasols?

Steampunks around the world now learn, practice, and occasionally duel with intent, but the World Championships are held annually in Calgary, where the sport originated. We’ve aligned with Beakerhead, that five-day festival where Arts & Sciences meet. Planning has just begun for next September’s Beakerhead, so I can’t give you details on that yet, but the Regional Championships are held during Calgary Comic and Entertainment Expo. Meanwhile, you can learn much more about the fictional and very real histories of Parasol Dueling at the Steampunk blog Gears, Goggles & Steam and on Facebook at Madame Saffron Hemlock’s Parasol Dueling League for Steampunk Ladies (hey, I didn’t give it that very long name!)

Fashion – that’s what I love about steampunk. You must have spent hours dreaming about the wardrobes, drawing them out and then finding just the right words to describe them so succinctly yet vividly. Can you tell us a bit about the process of creating your world of fashion?

Pictures. Lots and lots of pictures. That’s the short answer.

Steampunk fashion draws primarily from late Victorian style but interprets freely and is not as class-bound as it was in our history. Thanks be to Google for directing me to page after page of photos and discussions of original, preserved costumes as well as modern reproductions that are accurate in cut and – as much as possible – fabric down to the thread in the hand-stitched knickers. Before photography there were portraits, admittedly mostly of rich people, in which garments were thoroughly depicted. In Steampunk, I get to make my own fashion rules, and the rules governing Maddie Hatter’s fictional world are grounded in but not tightly bound by historical fashion.

But Maddie is a young woman skirting (pun not intended!) the precipice of the upper class and the middle class. How do her fashion choices reflect her chosen status?

But Maddie is a young woman skirting (pun not intended!) the precipice of the upper class and the middle class. How do her fashion choices reflect her chosen status?

Maddie’s clothing, as befits her modest lower-middle-class job, is fairly conservative in cut and colour. Browns and grays and blues instead of crimson, purple, and metallics. She sometimes yearns for the vivid and beautiful – and very well-tailored – gowns she used to wear when her father was footing the wardrobe bill. She retained a few good dresses from her Society life, but only those that could pass for a well-dressed journalist’s. They are now a few years out of date, which is good. Their age (in a fashion sense) demonstrates to the upper classes, on whom she reports, that she both understands good clothing and is not in competition with her supposed betters.

The upper classes assume Maddie bought her best dresses second- (or third-) hand, and don’t think less of her for that. Historically, lower classes wore clothing that was at least one full style-generation behind the upper classes; this was partly because employers often gave their out-of-style cast-offs to their servants as part of their wages and benefits (along with food and shelter), and partly due to a thriving trade in strongly-made second-hand clothing, which was often all the working classes could afford before widespread mass-production of clothing (imagine finding one of Jackie Kennedy’s or Princess Diana’s gowns in a consignment store).

Much of my research, and my fascination to date, has been in English fashion; however I will be exploring some other countries’ and other cultures’ fashions in future Maddie adventures.

The world you created includes homage to only one historical personage, Mr. Flinders Petrie. Why him?

The world you created includes homage to only one historical personage, Mr. Flinders Petrie. Why him?

I have great respect for history, and for humans whose deeds were sufficiently great to be recorded for posterity. The only truly historical personage mentioned in the Deadly Diamond is Mr. Flinders Petrie, one of the most respected of European Egyptologists, who was working in Egypt during the real-life period covered by our alternate-history. Mr. Petrie is generally credited with curtailing the wholesale upheaval of archaeological sites in search of treasures, and with ushering in a new standard for the recording and preservation of Egyptian antiquities. Without him, the history of Egypt would be far less complete. But, in a novella, there’s not a lot of room to be true to the known facts and foibles of historical individuals – or not as true as I would prefer to be – and thus Mr. Petrie alone gets his name on the page, as a mark of my respect for a man who changed history.

To the best of my ability, though, I accurately recreated the ranks of the various military personnel, the colonial structure of the British Protectorate in Egypt, even the dining room of Shepheard’s Hotel Anglaise in Cairo as it looked in 1898. It’s a world one technological tweak separated from our own.

So then your decision not to write an alternate history by including real people was deliberate. What aspects of the society did you focus on?

Because English-language Steampunk is almost entirely based in the manners and social structures of the late Victorian era, Queen Victoria is there by implication. Like monarchs before and after her, she gave peerages to industrialists who revolutionized the country’s economy. The Steamlords, my fictional class of peers, were first granted peerages around the time of the Napoleonic Wars, when steam power was just beginning to be harnessed for industrial and military purposes. These technological trail-blazers naturally made fortunes licensing and exporting their steam technologies, and gained power and prominence quickly as the 19th century Industrial Revolution unfolded….much to the dismay of those families traditionally close to the reins of power in England.

That concludes our interview, but if you’d like to read MADDIE HATTER AND THE DEADLY DIAMOND and see what other people have said about it, you can find it at Amazon and Tyche Books, and there are reviews on Goodreads.

Jayne Barnard is a founding member of Madame Saffron’s Parasol Dueling League for Steampunk Ladies and a longtime crime writer. Her fiction and non-fiction has appeared in numerous anthologies and magazines. Awards for short fiction range from the 1990 Saskatchewan Writers Guild Award for PRINCESS ALEX AND THE DRAGON DEAL to the 2011 Bony Pete for EACH CANADIAN SON. She’s been shortlisted for both the Unhanged Arthur in Canada and the Debut Dagger in the UK. You can visit her at her blog or on Facebook.

Jayne Barnard is a founding member of Madame Saffron’s Parasol Dueling League for Steampunk Ladies and a longtime crime writer. Her fiction and non-fiction has appeared in numerous anthologies and magazines. Awards for short fiction range from the 1990 Saskatchewan Writers Guild Award for PRINCESS ALEX AND THE DRAGON DEAL to the 2011 Bony Pete for EACH CANADIAN SON. She’s been shortlisted for both the Unhanged Arthur in Canada and the Debut Dagger in the UK. You can visit her at her blog or on Facebook.