A guest post by Amy Groening.

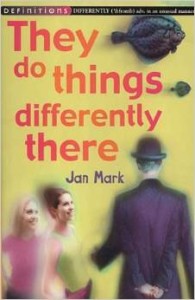

My family unearthed They Do Things Differently There (Jan Mark, 1994) at a library book sale when I was twelve years old. We had been consuming Jan Mark books for years and were very excited to discover a relatively new book of his shoved in amongst the clutter of salable discards. Every Jan Mark book I have read has endowed me with some new discovery of how to both play with the English language and appreciate life in general, but They Do Things Differently There was a crown jewel when I was young, and now, thirteen years later, I appreciate it all the more.

My family unearthed They Do Things Differently There (Jan Mark, 1994) at a library book sale when I was twelve years old. We had been consuming Jan Mark books for years and were very excited to discover a relatively new book of his shoved in amongst the clutter of salable discards. Every Jan Mark book I have read has endowed me with some new discovery of how to both play with the English language and appreciate life in general, but They Do Things Differently There was a crown jewel when I was young, and now, thirteen years later, I appreciate it all the more.

The account of a beautiful yet fleeting friendship between two dizzyingly creative teenaged girls, They Do Things Differently There offers clever descriptions of the realities of growing up in small-town Britain, a sardonic criticism of insincere aestheticism, and, most importantly, periodic vignettes of the deeper and much more bizarre episodes of an alternate reality, showing through in patches where the veneer of clean living has worn through.

I’m not talking about Blue Velvet, severed-ears-in-the-backwoods-type double lives; I’m quite sure Elaine and Charlotte would have balked at a crime so underwhelmingly average. Beneath the flowery, scrubbed-clean town of Compton Rosehay lurks Stalemate, a half-forgotten city that boasts a mermaid factory, a corpse-collecting manor lord and the respectable bunch of blackmailers keeping him in check, missionaries from Mars, and the Nobel Prize-winning creation of the Auger Scale of Tedium.

As ridiculous as the world of Stalemate sounds, Jan Mark uses these elements to create an effortlessly bizarre, unapologetically irreverent, and thoroughly enjoyable reading experience. It wasn’t until this year that I noticed the underlying references to pop culture and highbrow art that riddled the work. When I was twelve, mentions of Daleks flew right over my head, and I was under the impression that Mark’s cheeky rewriting of Wordsworth’s verse—Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive/But to be a fish was very heaven—was, in fact, just a clever bit of writing she had come up with herself. Even the book’s title is pulled straight from The Go-Between by L.P. Hartley. When Charlotte breaks the fourth wall and admits they’ve missed half a story because two pages of the book got stuck together, I was practically in convulsions of wonder. While I have now become accustomed to viewing this as a favourite trick of postmodern writing, back then it was the most mind-bogglingly clever writing twist I had come across.

This is one of the many things I love about Jan Mark: she created stories that I could enjoy as an uncultured preteen, and yet she didn’t seem to concern herself with the idea that a twelve-year-old might not catch references to high-brow literature (or British sci-fi shows from the 1960s). She didn’t pander to the lowest common denominator of undereducated schoolchildren, and yet she wrote books that said schoolchildren could still enjoy. I truly believe she wrote for a juvenile audience not because it was easier, as many people seem to think, but because it allowed her to freely exercise her complex, zany, and joyful yet melancholy writing style.

That being said, her novels do address serious matters—They Do Things Differently There is chock-full of loneliness, desperation, and the pain of being a social outcast. The stress of growing up, the terrifying powerlessness of childhood, the cruelty of adolescent alliances, and the dangers of depression come up in many of her stories.

Jan Mark was a prolific and well-respected British writer. When she passed away in 2006, she had published over fifty novels, plays, and short story anthologies, and had won the Carnegie medal twice, and yet the majority of her books are tragically difficult to come by.

When my family discovered They Do Things Differently There, it was out of print, as were Nothing to Be Afraid Of, a book of short stories we seemed to check out of the library several times a year, and Hairs in the Palm of the Hand, a book we finally procured a battered old copy of, which my sister still does dramatic readings of every Christmas. I have often wondered how a collection of books could be so principle in shaping my adolescence and my own writing aspirations, and yet so underappreciated, at least by a North American public.

For the longest time, I was under the impression we were the only Canadians who knew about these books. I was almost disappointed when They Do Things Differently There went back into print, assuming it meant Jan Mark was going to sweep North America and become a household name instead of a much-loved secret.

However, I still haven’t met any Mark fans who were not blood relations of mine; a quick visit to Amazon reveals not a single comment has been left on the They Do Things Differently There page, few ratings have been given, and while she does have a loyal fan base and blog articles devoted to singing the praises of her writing, her books are clearly still not being given the attention they so richly deserve.

Amy Groening is a publishing assistant at Word Alive Press. She is a passionate storyteller with experience in blogging, newspaper reportage, and creative writing. She holds an Honours degree in English Literature and is happy to be working in an industry where she can see other writers’ dreams come to life. She enjoys many creative pursuits, including sewing, sculpture, and painting, and spends an embarrassingly large amount of time at home taking photos of her cats committing random acts of feline crime.

Amy Groening is a publishing assistant at Word Alive Press. She is a passionate storyteller with experience in blogging, newspaper reportage, and creative writing. She holds an Honours degree in English Literature and is happy to be working in an industry where she can see other writers’ dreams come to life. She enjoys many creative pursuits, including sewing, sculpture, and painting, and spends an embarrassingly large amount of time at home taking photos of her cats committing random acts of feline crime.

East of Toronto, just off Highway 48, you will find a beautiful tree-lined campus right across the road from the famous Miss Scrimmage’s Finishing School for Young Ladies. It is Macdonald Hall, where generations of boys have been educated and prepared for manhood. Named for Sir John A. Macdonald, the Hall, with its ivy-covered stone buildings and beautiful rolling lawns, is the most respected boarding school for boys in all of Canada.

East of Toronto, just off Highway 48, you will find a beautiful tree-lined campus right across the road from the famous Miss Scrimmage’s Finishing School for Young Ladies. It is Macdonald Hall, where generations of boys have been educated and prepared for manhood. Named for Sir John A. Macdonald, the Hall, with its ivy-covered stone buildings and beautiful rolling lawns, is the most respected boarding school for boys in all of Canada.