Whenever someone asks me where I grew up, I claim Atlanta. Though I was born in Ottawa and lived on or above the Mason-Dixon line for the first fourteen years of my life, the person I am today came into being through the time I spent there. Though, I’m not a true southerner (you can’t be unless your roots go five or six generations back), I have picked up on some of their tricks.

When I first moved to the south, I remember thinking how nice and polite everyone seemed to be. A large part of the Southern social contract is devoted to avoiding overt conflicts. True, brawling does happen, but relations often stay friendly after wards. Things happen at a much slower pace, and no one really cares if you are two or three hours late to a bar-b-q. Southerners have turned hospitality and friendliness into an art form.

They have also turned sneakiness and subtly into a competition sport. In this arena, southern belles are the Olympic athletes. I’ve met women who can flay you alive and leave you thinking that they paid you the sweetest of complements. It’s actually pretty amazing to watch.

This tendency comes from years of practice in a culture and social system that strongly discourages direct physical conflict and prizes politeness and civility. However, when you try to disarm someone they will simply find another means to fight. Humans are still apex predators no matter how much we work to “civilize” them. We are also social animals who constantly struggle for their place in the clan’s heiarchy. When you take combat into a social arena, you simply change the rules, not human nature.

Where physical combat is an attempt to damage someone’s physical body or possessions, social combat is a war of perception and reputation. The combatants are trying to insult, slight, discredit, and embarrass one another in such a way that it influences the opinions and views of those around them. In so doing, the combatants are trying to change how others react to and interact with their target. Though more difficult and much longer term, social combat can also be designed to change how a person views themselves and how they in turn interact with the world around them. Break down someone’s self esteem, make them feel worthless and stupid, and they will break.

We are taught to ignore social combat as children, that “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me.” Unfortunately words, and the perceptions they alter, have incredible constructive and destructive power. Don’t believe me? Look at the absurd amounts of money political candidates pour into their media campaigns or the budgets that companies devote to advertising. These avenues are just mass social combat.

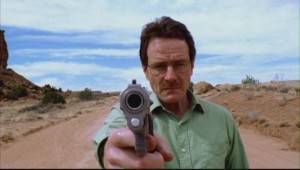

Social combat is nothing new to either life or fiction. However, it has seemingly had a resurgence in recognition and popularity. Reality TV is almost entirely based off turning social combat into a circus. Those sorts of bouts are more often like social brawls, however, lacking the refined elegance truly skilled combatants. For true social warfare, one can look to The Song of Ice and Fire books or their The Game of Thrones HBO made for TV adaptation. Many viewers love the politics and backstabbing as much, if not more than the physical conflicts. Some of the series’ most popular characters, such as Tyrion Lannister, Lord Varys, Little Finger, Tywin Lannister, Margaery Tyrell, and Melisandre, are beloved because of their skill and wit. In fact, the writers of The Game of Thrones directly call out the effects of social combat in a conversation between Varys and Tyrion in season 2 episode 3.

Varys: “Power is a curious thing, my lord. Are you fond of riddles?”

Tyrion: “Why? Am I about to hear one?”

Varys: “Three great men sit in a room, a king, a priest and the rich man. Between them stands a common sellsword. Each great man bids the sellsword kill the other two. Who lives? Who dies?”

Tyrion: “Depends on the sellsword.”

Varys: “Does it? He has neither the crown, nor gold, nor favor with the gods.”

Tyrion: “He’s has a sword, the power of life and death.”

Varys: “But if it is the swordsman who rules, why do we pretend kings hold all the power? When Ned Stark lost his head, who was truly responsible? Joffrey, the executioner, or something else?”

Tyrion: “I have decided I don’t like riddles.”

Varys: “Power resides where men believe it resides, it’s a trick, a shadow on the wall, and a very small man can cast a very large shadow.”

Social combat has a lot to offer fiction writers and our stories, but it is also difficult to use well. However, if you keep these six tips in mind, you can quickly find places to integrate this sort of conflict into your own writing.

- Not everyone is cut out to be a master of social combat. Most people are not particularly good at it or even aware enough to notice when it is going on. Do all your characters have huge muscles and advanced military training? Then why would they all be able to fence with grace and skill in the social arena? Characters who are masters of this sort of conflict are some combination of intelligent, witty, clever, well spoken, charismatic, and mentally nimble. Most importantly, they have experience using those attributes to influence others.

- People who are really good at social combat are also highly empathetic and perceptive. They understand how people will perceive their words and actions, and use that knowledge to create a desired effect.

- Social combat is still combat and should therefore have real and damaging stakes. After all, the diplomat and the swordsman both may be trying to kill you, but only one is doing so overtly. To ensure that proper tension is maintained, it is critical to make the consequences of failure are clear to the reader and the pacing appropriate to the conflict.

- Social combat is layered and filled with misdirection. Verbal sparring and the artful insults are rarely direct. Be sure to make full use of sarcasm, innuendo and referential humor (within the context of the story). Subtext is also a powerful tool. David Jon Fuller wrote a comprehensive post on this very topic last week, so I’d recommend taking the time to go look at it for some practical tips.

- If the conflict is too obvious, social combat becomes melodrama. However, if it is too subtle, it’ll be missed by all but the most astute. Where you shoot for on that continuum depends on your audience and how important the conflict is to your overall story. I have found a lot of success in using sequels and deep immersion to highlight social combat and its effects. After all, if your character is skilled at social combat they will be aware of when it is happening and will both plan for and react to social sparring matches.

- As writers, we have two major advantages over our characters when it comes to social combat. First, we have time to carefully think through and tweak each move in the conflict. Second, we enjoy unparalleled access to the thoughts and reactions of all sides of the conflict. Make sure you use these advantages for all they are worth!

Good luck and happy writing!

About the Author:

Though Nathan Barra is an engineer by profession, training and temperament, he is a storyteller by nature and at heart. Fascinated with the byplay of magic and technology, Nathan is drawn to science fantasy in both his reading and writing. He has been known, however, to wander off into other genres for “funzies.” Visit him at his webpage or Facebook Author Page.