Everyday living for most people can be compared all-too-easily to what drought means for farmers, what the dry seasons meant to American Indians. It’s a barren time full of silence and waiting and subtle, fatalistic dread that nothing is going to happen, that life will wither and perhaps even die. And it’s that need for green, for life and living, which brings comfort and joy and the heights of emotional salvation when the rains finally come. One could make the argument that we read drama and fantasy and horror because we have an inherent, hard-wired need for emotional input—a need for rain.

That’s a writer’s job, at least some of the time. We must don the doe’s skull and bright feathers. We must clothe ourselves in tanned hides and wrap bone rattles about our wrists and ankles. We must dance, sprouting clouds of dust as we stomp our feet and we sweat upon the hard-baked clay of everyday life.

It’s our job.

One of the hardest things writers have to live with is the uncertainty that their dancing has brought rain, sprinkled or poured a little bit of life into a reader’s existence. The truth is that most writers, especially at the beginning of their careers, never find out if their dancing has borne precipitation. There is this gulf—a fundamental disconnect—between writer and reader, one that leaves writers with cracked lips and dusty throats.

I recently had two experiences—more milestones in my career—which gave me tangible evidence that my own dancing was not in vain. Last fall I submitted a short story called Family Heirloom to the magazine Steampunk Trials. It’s a steampunk take on the Underground Railroad where a white widow and a freed slave build an Underwater Railroad in Missouri.

Included in the acceptance email was a very simple accolade, and one I’ll never forget. The story had brought tears the editor to eyes. When I wrote that story, it was with the absolute intention of touching, playing upon the heartstrings of the reader. I intended to bring forth the emotions of suffering and sacrifice, highlight the resolve of an individual to carry on and enrich the lives of the next generation in spite of tragedy.

Because of that first editor’s response, I chose Family Heirloom as the lead in a short story collection of mine that came out this summer. It’s not a best-seller in no small part because it contains cross-genre short stories, which is really a double-whammy against people even looking at it, let alone buying it. And yet, in spite of its uphill battle to gain recognition, I recently received another bit of rain. One of the reviewers up on Amazon said the same thing as the editor: that the story had brought tears to his or her eyes, and that other stories in that volume also had profound emotional effects. A reader took the time to let me—and the world—know that there was rain to be found between those pages.

For a writer, there’s nothing better than that.

So, to all the writers who read this, I can say but one thing: keep dancing. And to every reader, for all the rain you have been given by authors, give them some back. Give them the rain they need in the form of emails and reviews and word-of-mouth praise for the rain that has sustained you.

Drought is a fact of life, but we all possess the means by which we can bring rain to those who need it.

Q

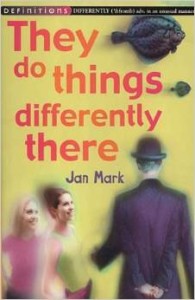

My family unearthed They Do Things Differently There (Jan Mark, 1994) at a library book sale when I was twelve years old. We had been consuming Jan Mark books for years and were very excited to discover a relatively new book of his shoved in amongst the clutter of salable discards. Every Jan Mark book I have read has endowed me with some new discovery of how to both play with the English language and appreciate life in general, but They Do Things Differently There was a crown jewel when I was young, and now, thirteen years later, I appreciate it all the more.

My family unearthed They Do Things Differently There (Jan Mark, 1994) at a library book sale when I was twelve years old. We had been consuming Jan Mark books for years and were very excited to discover a relatively new book of his shoved in amongst the clutter of salable discards. Every Jan Mark book I have read has endowed me with some new discovery of how to both play with the English language and appreciate life in general, but They Do Things Differently There was a crown jewel when I was young, and now, thirteen years later, I appreciate it all the more. Amy Groening is a publishing assistant at Word Alive Press. She is a passionate storyteller with experience in blogging, newspaper reportage, and creative writing. She holds an Honours degree in English Literature and is happy to be working in an industry where she can see other writers’ dreams come to life. She enjoys many creative pursuits, including sewing, sculpture, and painting, and spends an embarrassingly large amount of time at home taking photos of her cats committing random acts of feline crime.

Amy Groening is a publishing assistant at Word Alive Press. She is a passionate storyteller with experience in blogging, newspaper reportage, and creative writing. She holds an Honours degree in English Literature and is happy to be working in an industry where she can see other writers’ dreams come to life. She enjoys many creative pursuits, including sewing, sculpture, and painting, and spends an embarrassingly large amount of time at home taking photos of her cats committing random acts of feline crime.

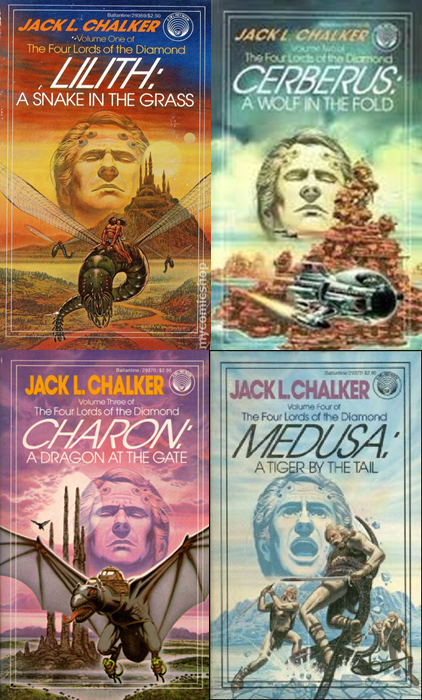

halker

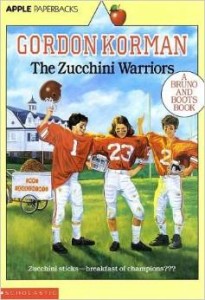

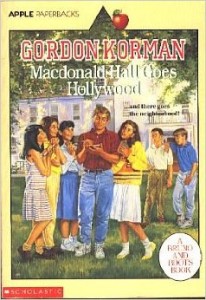

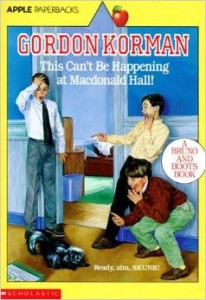

halker East of Toronto, just off Highway 48, you will find a beautiful tree-lined campus right across the road from the famous Miss Scrimmage’s Finishing School for Young Ladies. It is Macdonald Hall, where generations of boys have been educated and prepared for manhood. Named for Sir John A. Macdonald, the Hall, with its ivy-covered stone buildings and beautiful rolling lawns, is the most respected boarding school for boys in all of Canada.

East of Toronto, just off Highway 48, you will find a beautiful tree-lined campus right across the road from the famous Miss Scrimmage’s Finishing School for Young Ladies. It is Macdonald Hall, where generations of boys have been educated and prepared for manhood. Named for Sir John A. Macdonald, the Hall, with its ivy-covered stone buildings and beautiful rolling lawns, is the most respected boarding school for boys in all of Canada.