A guest post by David Farland.

I usually just hate flash forwards. Seeing one in a story is almost always a sign that the storyteller doesn’t know what he or she is doing.

You know what a flash forward, is, right? It’s when the writer violates the timeline by showing us something that will happen at the end of the tale.

Now, I’m the first reader for one of the world’s largest short story writing contests, so I see a lot of flash forwards. Most of them start with a tremendous amount of action, with the protagonist running for his life and then getting caught. Then the story flashes back to the character living up through the events that got him there.

The problem is, that in nine out of ten cases, those events are so slow, so boring, so routine or mundane that they just can’t hold a reader’s interest. On a conscious level, the author knows this, and so he or she will tack on a flash forward as if to say, “Keep on reading. It gets better!”

The problem is that the writer knows that the scenes as they are written can’t hold a reader. Usually, that’s because there is not enough conflict early enough. The protagonist doesn’t have any real problems, or they aren’t introduced within the first three pages. Or maybe there isn’t a central mystery that needs to be solved, or there just isn’t anything that is intriguing going on. There are just a few things that can hold a reader in the opening of a story. They are:

A fascinating setting or character, a character that is in pain or facing a significant problem, or a writer’s skill as a stylist and storyteller in presenting the story in an intriguing or powerful way.

If you don’t have any of those, you need them. In fact, if you don’t have them, you really should try to incorporate all of them.

Now, generally, a flash forward tends to be problematic. You see, when I begin reading a story, your goal is to engross me—to draw me into your fictive universe, transport me into your setting, let me take on the persona of your protagonist, and virtually live through a shared dream.

But a flash forward immediately kicks the reader out of that shared dream. Why? Because as soon as the flash forward ends, you yank your reader out of the dream. It’s as if the author is saying, “Oh, I was just kidding. This isn’t a story that you can get lost in. This is just me up here.”

In real life, you will never have a flash forward. You will never suddenly find yourself living through something that will happen in nine years. We are locked into a steady sequence of events, living from one second to another, and any violation of that law in fiction will cause a reader to disengage, even for a moment. You don’t usually want that.

Yet sometimes a flash forward can work. For example, in a science fiction novel, let’s say that you have a character who has prophetic visions. Go ahead and flash forward away!

Otherwise, you have to earn the flash forward. It can be done. Perhaps my favorite example comes from the plot of the television series Breaking Bad.

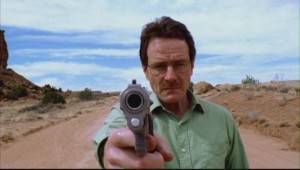

Here’s a description of that dramatic opening shot: A man (Bryan Cranston) wearing only underpants and a gas mask, drives a Bounder RV recklessly down a desolate road in the New Mexico desert. Another, younger man (Aaron Paul) with a gas mask covering a severely bruised face, unconscious, occupies the passenger seat. As the vehicle swerves down the dirt road, two bodies slide across the RV floor until the vehicle veers into a ditch. The hyperventilating driver climbs out with a video camera, wallet, and gun. Identifying himself as Walter Hartwell White, he records a cryptic, handheld farewell to his wife, son, and unborn child while sirens echo in the distance. Walt then steps onto the roadway, with the gun in his hand.

So why does the flash forward work so well on Breaking Bad but fail elsewhere?

- In this one, the audience really has to wonder what in the hell is going on—to the point that they’re willing to follow the story for an hour. Yeah, I really wanted to know how Walter White got himself into that kind of trouble.

- The following scenes must be interesting in themselves. They are. Breaking Bad was written beautifully, with an interesting character undergoing the fight of his life as he struggles with cancer, hoping to find a way to support his wife, his handicapped son, and his unborn child after his demise.

- The flash forward itself has to work as a hook for what happens next. At the end of this flash forward, Walter White appears to be making a stand—he’s going to confront the police. Too often, I see flash forwards where the protagonist dies in the flash forward, leaving no room for suspense as to what will happen next.

- The flash forward has to be interesting enough so that we are an audience are willing to see it twice.

- The flash forward has a twist in the end, taking us in an unexpected direction. When the flash forward does take its place into the story’s timeline, something happens afterward that changes everything—that either shows the protagonist in a new light, or shows the problem in a new light.

So, if you’re going to have a flash forward, you lose something. Most of the time, it’s not a tradeoff worth making.

If you are going to resort to a flash forward, make sure that every line of your story outside of it earns you the right!

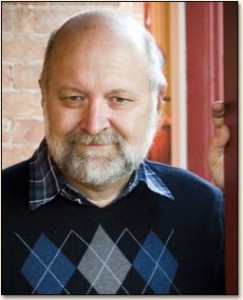

David Farland is an award-winning, New York Times bestselling author who has penned nearly fifty science fiction and fantasy novels for both adults and children. Along the way, he has also worked as the head judge for one of the world’s largest writing contests, as a creative writing instructor, as a videogame designer, as a screenwriter, and as a movie producer. You can find out more about him at his homepage at http://www.davidfarland.net/. Also check out more great advice in his book Million Dollar Outlines. And take some of his online workshops at http://mystorydoctor.com.