When I was younger, I had the fanciful notion that I would be a writer as well as a physician. Both of these were uncommon pursuits growing up in rural Prince Edward Island, and while both of these were viewed as fine goals, there were not many role models available locally for either of these. There was the kindly old family physician, of course, and he did in a pinch; in fact, it wasn’t until a significant chunk of the way through medical school that I decided upon neurology instead of family practice. But back then, I had an idea that his career would be someday my career. I would set out my shingle close to home and treat the locals. I had the idea that I would incorporate literature somehow into this-this was in the days before anyone had even thought of concepts like narrative medicine and patient stories-but I didn’t know how such a thing could happen. And I knew that I wanted to write things, perhaps even call myself a novelist, but I wasn’t sure how to make the two things fit together.

When I was younger, I had the fanciful notion that I would be a writer as well as a physician. Both of these were uncommon pursuits growing up in rural Prince Edward Island, and while both of these were viewed as fine goals, there were not many role models available locally for either of these. There was the kindly old family physician, of course, and he did in a pinch; in fact, it wasn’t until a significant chunk of the way through medical school that I decided upon neurology instead of family practice. But back then, I had an idea that his career would be someday my career. I would set out my shingle close to home and treat the locals. I had the idea that I would incorporate literature somehow into this-this was in the days before anyone had even thought of concepts like narrative medicine and patient stories-but I didn’t know how such a thing could happen. And I knew that I wanted to write things, perhaps even call myself a novelist, but I wasn’t sure how to make the two things fit together.

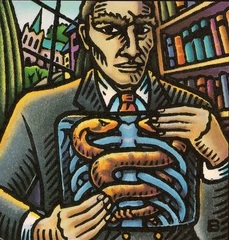

At the age of fifteen, I went to the local bookstore-I was already a voracious reader and spent my money there instead of on hockey cards, which was a Big Deal. While browsing, one paperback book caught my eye; the cover was a stylized portrait of a well-dressed man, a physician, holding a picture in front of him. But the picture was actually a chest X-ray, and the implication was that the sternum, rubs and clavicles were those of the doctor. Wound around the sternum, coiling between the intercostal spaces of the ribs, were two serpents, staring each other down in a semblance of the staff of Mercury associated with the medical profession.

The book was The Cunning Man, by Robertson Davies. The back cover told me that it was a memoir of a doctor’s life, and promised the story of a doctor who knew his patients’ souls as well as their bodies. This was exactly what the Fifteen-Year-Old Me needed, wanting to find a middle ground between my medical ambition and my interest in literature. I bought the book, and then spent the next several years buying every book by Robertson Davies that I could find. In the years since, I have constantly gone back to reread his novels, his essays, his letters, and they have always had something to say with regard to either-or both-of those worlds.

Many Canadian students know Davies through his Deptford trilogy; Fifth Business is required reading in many high-school English courses, though I was never so fortunate. His writing was very literate; you had to work to understand his stories, but if you did, you would be rewarded with the richness of his language, the depth of his characterization, and the breadth of his interests, everything from small-town theatre to Jungian analysis to academia. He could be wickedly, savagely funny, and he was not always kind, as many of the characters were thinly veiled composites of the pretentious and the stupid. But the writing was never preachy, or awkward; he was a writer who expected the literacy of his readers, and his readers, me included, were proud every time their efforts were rewarded with some sage bit of wisdom or some interesting jewel to share.

I devoured his novels, and even tried to ape his style in my own writing (of course it never worked!) but as I grew older I found more and more inspiration from his essays and his letters. Several books of essays and speeches were published after his death; in one collection, The Merry Heart, he published a speech he had given to medical undergraduates titled Can a Doctor Be a Humanist? This one went right to my heart’s core. He talked of how the truly great doctors didn’t just consult lists of symptoms or mindlessly offer pills, but took the time to listen, to let the patient’s symptoms tell the true story of what was happening. He also spoke of the background of the medical profession, and the mythology behind the staff we use as our symbol, and most of all how we can balance Wisdom with Knowledge to become a truly great humanist physician.

He died shortly after I discovered him-one of life’s many small cruelties-and so I have been left sifting through his writing and the words he left behind, knowing that there won’t be any more, but still finding jewels of inspiration every time I read his work. There have since been many role models, literary and medical, but none have bridged those two worlds so successfully. I am still very early on my path as a physician, and I am still trying to find a way to have literature and writing be a part of that journey, but I can say with conviction that had I not found that book all those years ago, I would not be half as good at either of those things as I am today.