Whenever I begin a new writing project, I know I’m building on what I’ve learned from previous projects. Having written non-fiction for over two decades, and fiction for a few years now, I’ve come to recognize certain patterns in my writing habits that have been formed—both consciously and unconsciously—by my previous efforts. All my new beginnings follow a long chain of old endings.

In simple terms, it’s the learning process. My articles and book chapters, my short stories and novellas, all contained both successes and failures: things that worked, things that didn’t. Yet each one taught me something that I could take into the next project. The failures, if I’m honest, are the better teachers. That’s where the real learning is done. And the failures don’t need to be epic. Simple mistakes, recognized for what they are, show me what to do differently next time.

For example, my first professional fiction sale (a short story to an anthology), contained a fairly subtle yet significant example of floating viewpoint: “head hopping,” as it’s better known (where the point of view suddenly switches from one character to another without any cue to the reader that it’s happening). In my case, I was too inexperienced at the time to recognize what I had done, and it was subtle enough that the editor himself didn’t notice it until his second or third pass. (It was a scene in a séance, wherein I jumped blithely between the main character, a man trying to contact the dead, to the old woman who was leading him though the ritual.)

When the editor caught it and pointed it out to me, I was sufficiently mortified (another classic newbie move—overreaction!). But I also learned why head hopping was a problem, how it can disrupt the flow and pull the reader out of the story. I have been careful not to make the same mistake again. (Don’t misunderstand: many very good authors head hop through their characters all the time, and do it well. But not me, not then.)

The point: it was a learning experience. One that I wouldn’t have made had I not given that project my very best efforts, and made a sale to a good editor who then helped me improve the story. Because even my best at any given time will have shortcomings. Only by pushing myself will I make mistakes I can really learn from them. These are the good mistakes. The “new mistakes,” I now call them, stealing a line from the Shakira Zootopia song “Try Everything.”

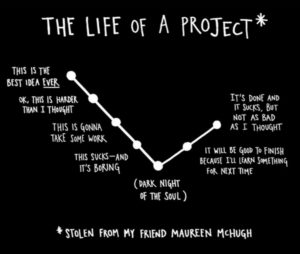

Speaking of stealing, the best illustration I know of the process of making these “new mistakes” comes from one of my favorite books, Steal Like an Artist, by Austin Kleon. I think it speaks for itself:

(Image source: tumblr.austinkleon.com/post/102479069106. Note that Kleon himself stole this from Maureen McHugh!)

It’s a great illustration from a great book. Notice, however, that implicit in the “life of a project” is that we must complete our projects. For fiction writers, this is the equivalent of Heinlein’s second rule of writing: finish what you start. That’s the best way to learn. Even the epic fails, the stillborn ones destined for the scrap heap, teach us something … even if it’s just the extent of our current shortcomings.

But finish. Learn what you can. Then start something new.

Starting a new year is a lot like starting a new story. We can look back on the successes and failures of the ones we’ve finished, figure out what we’ve learned, and then begin a new one with a little more confidence.

Here’s to 2017—may it be full of new beginnings built on old endings.

Steve Ruskin has been a university professor, a mountain bike guide, and a number of things in between. In addition to fiction (most recently the sci-fi novella A Deal with the Devil’s Broker) he has written for academic and popular audiences in publications ranging from the American Journal of Physics to the Rocky Mountain News. Visit steveruskin.com.

You know when you’re knee deep in a project and then you get that shiny new idea? And you’re like, “But Brain, I don’t write Historical Fiction. You must have me confused with a better brain that likes to research things to death.” And yet, you love the idea so much, you decide, maybe one day, you’ll write that shiny idea into a book or short story, or *gulp* a series.

You know when you’re knee deep in a project and then you get that shiny new idea? And you’re like, “But Brain, I don’t write Historical Fiction. You must have me confused with a better brain that likes to research things to death.” And yet, you love the idea so much, you decide, maybe one day, you’ll write that shiny idea into a book or short story, or *gulp* a series. Read.

Read.