Many genres hand over arsenals of handguns to their characters to use as they stumble through the complex plot their writers have invented. From the trusty Western six-shooter to Han “I Shot First” Solo’s blaster, guns are an integral tool of the trade.

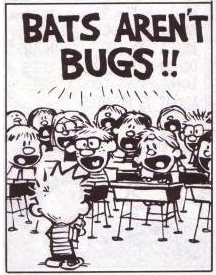

When a writer has no first-hand knowledge of how to use any firearms, and let me note that this is an excellent personal choice for those who prefer never to touch a gun, they still have to write about the use of a handgun without driving their readers away. Otherwise, one can come up with disasters like this picture, which went viral on Facebook because the poor young man was clueless.

For those who don’t know, the young man is holding a revolver and the magazine from a different weapon in one hand, as though the revolver used magazines. They don’t — you can see the revolving cylinder above the trigger that holds typically five or six rounds. People had a good laugh, even though the gentleman seemed far too young to legally have a handgun and his finger was on the trigger while posing. Others posted their versions of the Clip-a-zine picture using other objects that one does not usually use with a revolver.

With that said, let’s discuss some common issues that annoy readers who have a familiarity with handguns.

Rounds, Cartridges, Bullets — Oh My!

Let’s start with the little items that pop out and cause damage to others. A round or cartridge is a complete package, ready to load and fire. It includes the actual projectile, called a bullet, gunpowder, a primer that starts the process of expelling the bullet at a high rate of speed, and a casing that holds them all together. In the early days of handguns, one would put powder into the barrel of a weapon, add in some wadding, and then jam a bullet on top. Once that was accomplished, one would either use a primer or some sparking method like a flint to cause the gunpowder to explode.

When someone came up with the idea that one could make reloading fast and efficient, it was a game-changer.

Revolvers

Some law enforcement officers prefer revolvers because they normally don’t jam unless severely damaged. Some use them as a backup weapon just in case their semi-automatics jam. A pistol is another name for a semi-auto handgun, not a revolver.

As mentioned, a modern revolver has a cylinder that holds rounds, or cartridges. When the trigger is pulled, the cylinder is rotated so that a cartridge is lined up with the barrel. The hammer then falls on the firing pin, which strikes the primer. The primer starts a tiny explosion that causes the gunpowder load to burn, which expands rapidly and forces the bullet to exit the barrel of the weapon. Pulling the trigger again repeats the process. Some older revolvers required the user to “cock” the weapon by pulling the hammer back until it locked. Modern versions typically allow one to cock the weapon or to have the trigger pull back the hammer before releasing it.

Older versions of the revolver were hand-loaded as previously described. A built-in lever allowed the user to compress the bullet against the wadding and the gunpowder. Sometimes they would also add in a bit of grease on top of the loaded cylinder to prevent cross-firing, which could cause the revolver to detonate. Clint Eastwood uses a hand-loaded revolver in several of his movies, and some of the early revolvers allowed the gunfighter to swap out a fully-loaded cylinder.

After the usual six shots are fired with a modern revolver, the user has to remove the spent casings and load in fresh cartridges. Police officers who prefer revolvers tend to have small round devices called speed loaders, which hold six rounds with a device that allows the user to reload faster than doing so individually.

Semi-Automatics or Pistols

Semi-automatic pistols have been around for over a hundred years. These weapons are designed to hold more cartridges and to allow the user to reload quickly using a magazine. Note that the magazine is sometimes called a clip, which is actually incorrect. A clip is a device that holds several rounds together and allows a user to slide a set into the magazine. Rifles such as the Russian-designed SKS use these clips, sometimes called stripper clips, to load the built-in box magazine. Modifications allowed the rifles to use larger removable magazines that were hand-loaded with cartridges. So many people call magazines clips that they’re becoming equivalent, but it is something that drives some readers crazy.

Pistols use these magazines to hold a lot of rounds. Some stagger the rounds, making the grip thicker, but allowing for seventeen cartridges in the magazine and an additional one pre-loaded in the barrel and ready to fire. The large improvement in the number of available rounds before reloading is why many users switched to pistols. The down side is the semi-automatic is more complex and can jam, making the pistol useless until fixed. Revolvers, with their built-in simplicity, typically do not have this problem.

A semi-automatic will fire a single shot every time the trigger is pulled. The force of the exploding gunpowder forces the top slide back, ejecting the spent casing and automatically allowing the next cartridge to load into the barrel. Some semi-automatics will also push the hammer back to fire, while other designs use the movement of the trigger to move the hammer back.

While there are fully-automatic pistols available, they are very rare and expensive, requiring a special license to own. With such a limited number of rounds in the magazines, a fully automatic pistol would be empty in a couple of seconds.

Recommended Actions

Assuming you are not adverse to trying to fire a weapon on a gun range with experts to help you, I would recommend you do it for the experience. It will help your writing, and you will get additional safety tips from your instructor. If you do not wish to ever handle a weapon, I would recommend you go to a gun range and have an instructor demonstrate everything for you. Either method will allow you to experience being in the presence of a weapon firing. Note that it is incredibly loud, especially if your characters fire in an enclosed space. Their ears will be ringing for quite a while, something that tends to be forgotten. A military user or a law enforcement officer always counts down when they fire so they know how many shots they have left. Above all, anyone who has handled weapons and has had any training knows that one always treats any weapon as though it was loaded. Never point it at anything you don’t want to hit, even accidentally, and always keep your finger off of the trigger unless you are ready to fire the weapon.

Generally, I think authors write young, female characters very well. I know what you’re thinking. But Kristin, this month is all about how authors get things wrong! You’re supposed to point out instances where a writer wrote a young woman incorrectly!

Generally, I think authors write young, female characters very well. I know what you’re thinking. But Kristin, this month is all about how authors get things wrong! You’re supposed to point out instances where a writer wrote a young woman incorrectly! The research in the article states

The research in the article states