An interview with Sonia Orin Lyris.

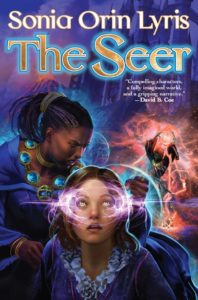

Our theme this month is memorable characters and that makes it a great opportunity to interview Sonia Orin Lyris about her debut novel, THE SEER.

In creating the Arunkel Empire, Lyris blends the realities of being a commoner and the ruling classes, the complex politics of the Houses vying for the Palace’s attention amidst rebellion, treason, and treachery. It is this world that Amarta the Seer must successfully navigate not only to save her sister and baby nephew, but to realize that as she predicts the future, she can create it.

In creating the Arunkel Empire, Lyris blends the realities of being a commoner and the ruling classes, the complex politics of the Houses vying for the Palace’s attention amidst rebellion, treason, and treachery. It is this world that Amarta the Seer must successfully navigate not only to save her sister and baby nephew, but to realize that as she predicts the future, she can create it.

Not only has Lyris created a truly memorable world, but there is a ring of truth about her characters which resonates long after the book is done. (Be warned: some mild spoilers are included in the questions and answers below.)

The seer, Amarta, is introduced as a young child who has a rare talent. Being the child, she’s too young to understand it except to know that the things which she sees happen and they’re not pleasant. As she grows into young adulthood she and others pays heavy prices as she tries to evade pursuers who covet her talent. I’m curious about starting with such young child, for that’s rarely done, and what her talent and her journey mean to you.

As an author, I have a particular responsibility when writing a coming-of-age story, like THE SEER. I have an obligation to neither dumb-down the child Amarta nor to overestimate her abilities.

When the door opens in chapter one, we meet a child who has already had a difficult life, yet she’s been sheltered and is naive in many ways, knowing little of the greater world in which intrigue and treason is occurring. Her visions tell her things she can’t possibly understand yet, but she must try to, if she is to survive.

I wanted Amarta to be a whole person. Even as young as she is, she’s not simple. She has a family she loves. There is loss and pain in her past. She is struggling to understand what she is.

Who would she become, I wanted to know. Who must she become, to be able to take on the great power that she has come to hold?

The story starts with her so young because the challenges these questions raise start early. These challenges are the seeds of her journey.

There are mages in the novel. Mage live long, are capable of many powerful things. When we meet Maris, we quickly learn that there is a great cost to become a mage, paid not only by her parents, but also by her during her training. Unlike most other novels where the wizard or mage talent is taken for granted, you address the cost of becoming a mage as well as the cost, both personal and indebtedness, of taking on a contract.

Yes, mages pay dearly for their power and status. In Maris’s case, her parents paid a price as well.

You know the old adage that great responsibility comes with great power? This is a moral stance that the very powerful must come to understand out of their experience because no one can force them to take it. I wanted to explore the cost of achieving such power, and examine the consequent responsibility.

The contract Maris takes on to undergo the transformation into mage — her apprenticeship contract — is one that typically ends in success or in death. High stakes, over many years. It’s not a pretty business, and Maris’s personal experience of that is very much part of her journey.

At one point in the story, Maris is talking about what it would mean for someone to become a mage. She thinks: “It would break him, rip his world to shreds. Change everything he thought he knew.”

I wanted to know more about her journey. Where had she come from? Where would she go? Would she resolve her bitterness at the cost she had paid?

An interesting parallel exists between the struggles of royalty and the commoner. I’m thinking of Cern, the king’s daughter who becomes queen because of her betrothed’s treachery, and Amarta, the seer. Both have responsibilities due to fate. Both are forced into roles they don’t choose and their actions or inactions have profound effects on a kingdom. Yet, their character arcs are so different.

Yes, both Amarta and Cern are both thrust into responsibility without choice, and their arcs are very much about this unchosen power. Cern has every advantage of education and wealth, but she struggles with an isolated and loveless familial existence that shapes her every step toward the throne. Amarta has the very wealth that Cern lacks — family and true loyalty — but lacks the rest.

What they share, perhaps ironically, is that they are both living under dire threat, and neither is safe in the world, except as they learn to make themselves so.

To what lengths would I go to have power? I found myself asking that question because of Innel, a commoner who is raised in the Palace’s Cohort group. He’ll do anything to please the King, to earn his respect so he can have a chance at marrying the princess Cern. He is, at once, fascinating and terrifying, and this balance is hard to achieve for many writers. Can you share with us how you so deftly managed to create Innel and what is it about him that made you want to write him?

Power is so interesting. The more you have, the more it has you.

As the story opens, we see this forceful, wealthy man show up at the door, intent on lethal answers from Amarta. In chapter two we find out more: who he is, what he’s done. Then the consequences of his earlier actions begin to unroll.

I had to do more than say Innel was ambitious and close to the throne. He had to make sense in the context of his history and culture, all the way back to childhood. We see more about this childhood in “Touchstone”, a tie-in story available for free on the Baen website, where we find out how he and his brother came to the Cohort.

I wanted to go deep into Innel’s journey in the novel because he balances Amarta’s journey. What, I wondered, had happened in his past that drove him to the circumstances of chapter one? What was it like for him to stand so dizzyingly close to such monarchical power?

Again, it’s about making him a whole person, with all the conflicts and convictions that someone in his position might actually have. What is he afraid of? What does he want?

And how far will he go to get it?

Here’s the ‘where did you get the idea?’ question. The hidden city of Kusan where the slave race, the Emendi, live is brilliant. I found myself wanting to visit this tangle of warrens in the hills and to learn their secret language. What inspired you to create this society?

As it happens, you can visit Kusan – or nearly so — because Kusan is based on the underground city at Derinkuyu, Turkey, a subterranean city thousands of years old that descends many levels. The actual city is big enough to house thousands of people, along with their livestock and supplies. Highly defensible, the entrances could be sealed with huge stone doors. It had underground wells of fresh water, ventilation ducts, and an extensive network of rooms and stairs and tunnels. Across its history, the underground city at Derinkuyu many times served as a refuge.

When I heard about this underground city, I knew at once that it was my hidden city, the novel’s Emendi haven. The Emendi were long ago abducted from across the waters, brought back, and forced into slavery. Emendi are blond, and there is a long-standing folktale that the gold of their hair implies pure gold inside their bodies as well. In the face of this story, is dangerous for them to be in the open.

And yet, over many years, some managed to escape. Kusan — the Hidden City — is where they found refuge, and now live, quietly and safely.

But again, we’re talking about real people, with complicated motivations beyond freedom and survival. The Emendi have created their own hidden culture in the subterranean city of Kusan. They have a signing language, one they developed in the halls of their captors, and keep alive so that they never forget where they came from, or forget the family they left behind, who are still enslaved. They have traditions of stealth and caution. They are especially cautious about their oppressors, the Arunkel people, who live above ground all around them.

Want to see what Kusan looks like? Here is a collection of photos of the underground city at Derinkuyu, in Turkey:

http://scribol.com/anthropology-and-history/archaelogy/turkeys-incredible-lost-underground-city/

And one final question: You’ve created a world which feels very real and with it a full complement of memorable characters. Do you have any advice on creating memorable characters?

There many ways to create memorable characters. Lots of techniques. The scope of them can be daunting, especially if a writer does not naturally tend toward the character-oriented approach.

But rather than hand over a fish, let me tell you about my pole and bait.

In a story of memorable characters, each character is the protagonist of their own tale. Even the least consequential of them has a past, a family, a culture, just like the flesh-and-blood people around us.

So I ask myself: what does the world look like from their point of view? Where are their joys, their terrors? What do they care about?

I’m not suggesting a writer must describe all that, but do have a feel for it. Just as the people around us have personalities, so do story characters. To get better at understanding this, I recommend studying good examples, such as the flesh-and-blood characters around us.

What makes them tick? What makes them joyful? What pisses them off? How do they explain themselves? What is the story they tell themselves about who they are and what they are doing in the world?

If you listen well, with compassion and curiosity, people will talk plenty. As they do, imagine what they must feel like inside. Step into their shirts and shoes. Wiggle your fingers and toes. How does it feel to be there? What is this person about?

Then do the same with your characters.

A hearty thank you to Sonia Orin Lyris for this interview. For a copy of THE SEER, check with your favorite bookstore or find it online at Baen or Amazon. Gain deeper insight into the Arunkel Empire and the significance of its coinage by reading her guest blog for us titled Will Build Worlds for Spare Change.

Jean-Luc Picard is the ultimate philosopher king (but this guy is a close second). The term “philosopher king” is thrown around quite a bit, but let me take you back to its origins. Plato wrote, in Republic:

Jean-Luc Picard is the ultimate philosopher king (but this guy is a close second). The term “philosopher king” is thrown around quite a bit, but let me take you back to its origins. Plato wrote, in Republic: Evan Braun is an author and editor who has been writing books for more than ten years. He is the author of The Watchers Chronicle, a completed trilogy. In addition to writing science fiction, he is the managing editor of The Niverville Citizen. He lives in Niverville, Manitoba.

Evan Braun is an author and editor who has been writing books for more than ten years. He is the author of The Watchers Chronicle, a completed trilogy. In addition to writing science fiction, he is the managing editor of The Niverville Citizen. He lives in Niverville, Manitoba.